|  | Know better. Do better. |  | DataveillanceAI, privacy and surveillance in a watched world |

|

| | | By Samuel Woodhams | Digital rights researcher and journalist | | |

|  |

| Hi, it’s Sam. This week, we’ll consider the privacy implications of biometrics and look at some recent lawsuits challenging its use.

Peoples’ physical features are being digitally recorded and analysed on an unprecedented scale, with new biometric technologies deployed in workplaces, homes and at borders around the world. Governments and businesses say the systems improve the efficiency and security of everything from passport control to hospital admissions.

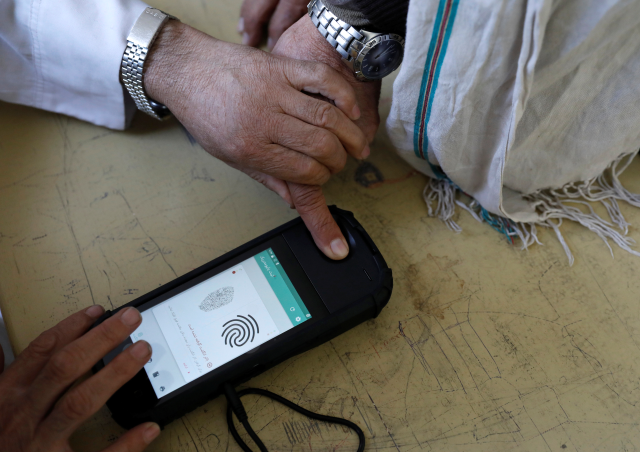

But digital rights advocates have long warned of the privacy risks associated with biometrics, and now a growing number of companies are facing legal action for using the systems without peoples’ consent.  An election official scans a voter's finger with a biometric device at a polling station during a parliamentary election in Kabul, Afghanistan, October 20, 2018. REUTERS/Mohammad Ismail |

Data privacyBiometric technologies can analyse a wide range of physical and behavioural characteristics, including an individual’s voice, face and gait. The most common function of these tools is to automatically identify someone to allow them to vote, board a plane, buy school lunch, or unlock a phone.

Although some of these products seem futuristic, using physical characteristics to determine someone’s identity has been around for hundreds of years. In fact, fingerprint analysis can be traced all the way back to the Qin Dynasty. Unfortunately, outdated ideas still influence biometrics, with several so-called criminality-detection tools bearing a disturbing resemblance to the racist pseudoscience of phrenology.

To appreciate the true risk of biometric surveillance we should look to Xinjiang, where a vast biometric surveillance system has been established to monitor nearly everyone in the region. The database includes the fingerprints, iris scans, DNA samples, and blood types of residents, who are largely Uyghurs. Coupled with the extensive use of facial recognition cameras, China’s use of biometrics shows what can happen when authorities have unfettered access to our physical data, and the repressive ways in which it can be used.

Not only can biometrics be used to surveil, they can also be used to exclude. In India, for example, millions of children are at risk of being excluded from education because they don’t have Aadhaar ID cards which store biometric data.

The facial scanning technology many of us use on a daily basis to unlock our phones or scan our passports may seem harmless in comparison, but with few regulatory restrictions there’s a risk the technology can be used for more malicious purposes – or even just to bully rivals, as the owner of Madison Square Garden is doing to keep out lawyers from firms engaged in litigation against the company.  An election worker takes a picture by biometric device in the presidential election in Kabul, Afghanistan September 28, 2019. REUTERS/Mohammad Ismail |

Legal challenges to biometricsStill, people are finding ways of fighting back. In the United States, in particular, citizens are using the courts to defend their biometric privacy and seek compensation when the technology has been misused.

Illinois has become “the filing capital of biometric privacy lawsuits” thanks to the Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA). Introduced back in 2008, it gives citizens the right to control their biometric data, and prevents companies from collecting their information without consent.

In a class action complaint filed at the end of last year, a Chicago-based public parking company was accused of “invasively and surreptitiously captur[ing] images of its customers’ faces for identity verification purposes.” It’s alleged that the company failed to inform people of the purpose of the scanning, how long it would store the images, or obtain signed consent. The case will be heard later this year.

Large tech companies have also been caught out. Last year, Snapchat’s parent company Snap Inc agreed to pay $35 million for violating BIPA, while Google paid $100 million after being accused of using peoples’ personal photos to train its facial recognition algorithm.

Across Europe, the facial recognition firm Clearview AI has been fined for scanning people's photos online without their consent. The company was found to have breached General Data Protection Regulation in the UK, Italy and Greece. It has also faced legal repercussions in Canada and Australia.  Visitors check their phones behind the screens advertising facial recognition software during Global Mobile Internet Conference at the National Convention in Beijing, China April 27, 2018. REUTERS/Damir Sagolj |

Are existing safeguards enough?While the legal challenges facing biometric technology is undoubtedly a positive step, few seem likely to dramatically alter the trajectory of the industry. Instead, they are often only minor setbacks for huge companies with an unwavering desire for more and more data.

The EU’s AI Act could introduce more stringent requirements on the processing of biometric data but, in its current form, it seems unlikely that it will completely limit governments’ and companies' use of the technology. Similarly, while the rise of state-level biometric legislation in the United States should be applauded, much more is needed to effectively limit the technology’s potential to undermine human rights.

Until more comprehensive and meaningful regulations are introduced, I’m inclined to agree with Madeleine Chang of the Ada Lovelace Institute who has called for a moratorium on the problematic uses of biometrics until human rights can be meaningfully protected.

Any views expressed in this newsletter are those of the author and not of Context or the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

We're always happy to hear your suggestions about what to cover in this newsletter - drop us a line: newsletter@context.news

Recommended Reading

Bloomberg Law, The evolution of biometric data privacy laws, Jan. 25, 2023

This article explores the development of biometric data privacy laws across the United States and provides a useful comparison between legislation in the states of Illinois, Texas and Washington.

Eileen Guo and Hikmat Noori, This is the real story of the Afghan biometric databases abandoned to the Taliban, M.I.T Technology Review, Aug. 30, 2021

This article delves into the collection of biometric data in Afghanistan and explores the risk it posed to people following the Taliban’s takeover of the country. It finds that rather than U.S. biometric devices posing a risk, it was the Afghan government’s own biometric databases that may have been used to identify millions of people in the country.

Allie Funk, I opted out of facial recognition at the airport - it wasn’t easy, Wired, July 2, 2019

What happens when a technology becomes so pervasive that opting out no longer feels like a genuine option? This article shows how difficult it is to opt out of facial recognition at airports, and explores what it means for our data security and privacy.

Human Rights Watch, China’s algorithms of repression, May 1, 2019

This article has more information on China’s use of biometric surveillance in Xinjiang and explores how it is interconnected with other forms of surveillance. It also has several important recommendations for China’s authorities and governments around the world. |

|

|

| | The rollout of digital ID Fayda in Ethiopia could entrench discrimination against Tigrayans and other ethnic minorities, rights groups fear | Greater public participation in decisions on resource-intensive projects such as data centres can increase acceptance | The Online Safety Bill aims to protect users from harmful content, but women's groups say it does not go far enough | Wikipedia's ban of 16 users in the Middle East highlights attempts by Saudi Arabia to control online spaces, rights groups say | Cybercrime laws are used to attack freedom of expression, undermine privacy, and tighten control over legitimate online activities | |

| |

| | | |

|