Americans move to climate-risky areas as real estate booms

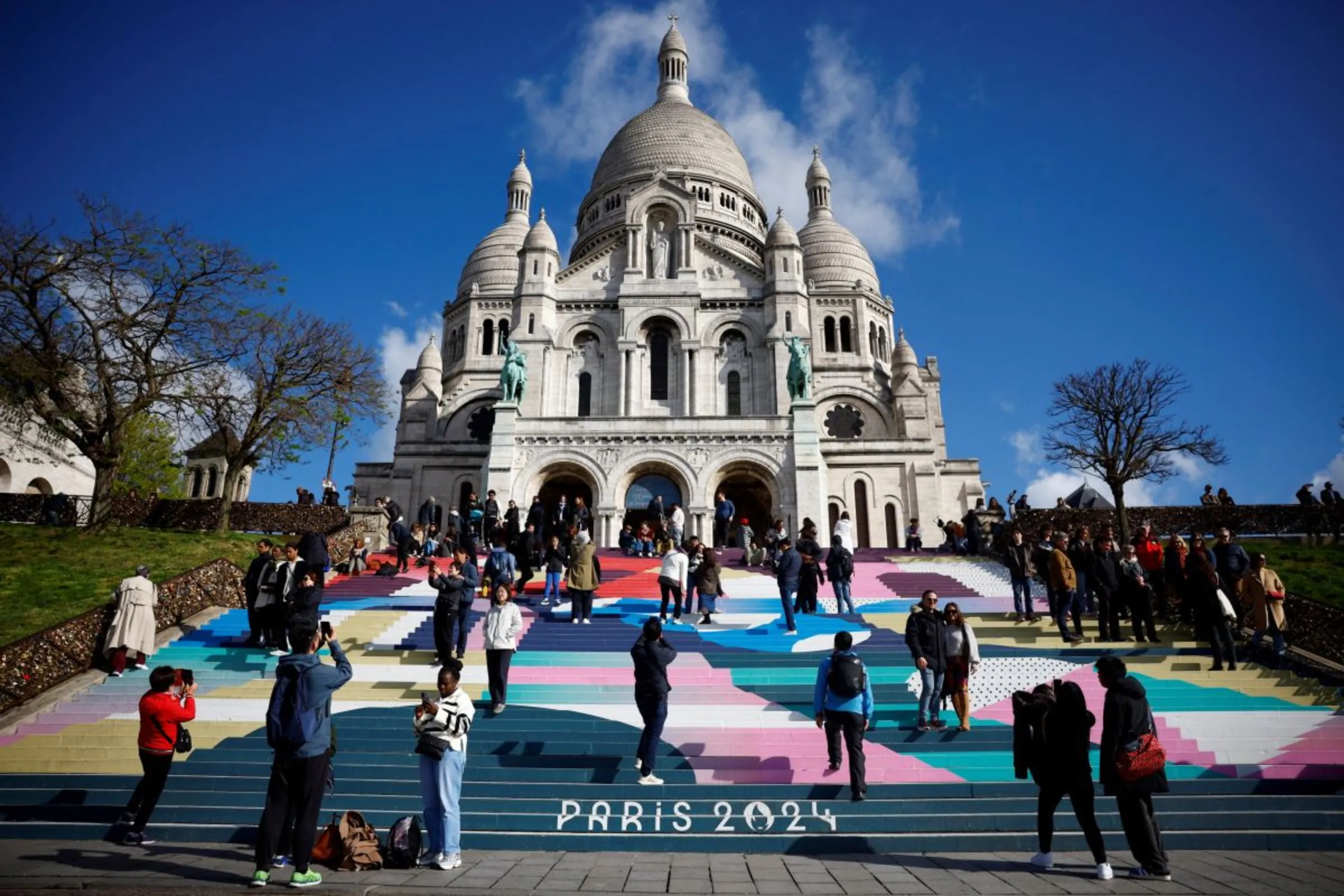

A sign next to a road leading toward the Battleship North Carolina, across the Cape Fear River from downtown Wilmington, warns drivers in North Carolina, USA, February 29, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/David Sherfinski

What’s the context?

How growing battles over real estate development and flood risk are playing out in one community on the U.S. East Coast

- Officials mull new development near downtown Wilmington, NC

- Coastal areas in U.S. to face increased sea level rise, flooding

- Americans moving toward climate-risky spots

WILMINGTON, North Carolina - Robert Parr drove his white pickup truck near a set of new buildings near the beachfront in New Hanover County, North Carolina – an area he says is prone to flooding.

"That's crazy. That never should have gone in here," he told Context, referring to new development blocks away from the U.S. East Coast.

"Whenever I get on the phone with the county, usually within 30 days we have significant flooding," said the former oceanographer, after opening a presentation and flicking through slides of flooded roads and areas around the region.

The burgeoning county has faced a barrage of recent storms and is at major risk of flooding again over the next 30 years, according to First Street Foundation, a climate risk tracking group.

Parr and other activists are racing to prevent another major development on an approximately eight-acre patch of land farther north, across from downtown Wilmington, in a spot uniquely prone to flooding.

Precisely how to build in floodplains and areas most at risk from climate change amid continued population growth is an issue U.S. officials are grappling with as people and developers move into – not away from – perils like flooding and wildfires.

"The challenge of managing climate risk in the long term is much, much harder if we continue to develop in hazardous places the way we have been to date," said Miyuki Hino, assistant professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of North Carolina.

Development

For years, local officials have been grappling with what to do with a tract of land along the western bank of the Cape Fear River across from Wilmington – an area that floods relatively routinely even outside of major storms.

Much of the patch nearby is still zoned industrial, and options range from expanding open space to rezoning the area to allow for high-density, mixed-use development.

Developers had proposed three multi-story towers, 550 condominium units and 300 apartments for a spot known as Point Peter, at the confluence of the Cape Fear River and Northeast Cape Fear River, but the project stalled in 2021 as county officials wanted more time to assess longer-term plans.

Kirk Pugh of KFJ Development Group, the project's developer, is frustrated with the slow pace – and said building in and around the Cape Fear River area can be done safely.

The original concept included a "sacrificial first floor" and a stormwater capture and release design among the features, he noted, that would allow water to move "freely" if a freshwater flooding event occurred.

"The argument that we shouldn't build in a floodplain ... well, most of our county is in a floodplain," he said.

Those opposed to building up the area say it does not make sense to pursue even scaled-back versions, given the long-term trends of sea level rise and climate change fuelling more intense storms and flooding in the region.

"Risky isn't even the right word," said Kemp Burdette with Cape Fear River Watch, an advocacy group. "Risk indicates that something might happen or it might not happen. A flood over there is inevitable."

Wilmington's location toward the end of the massive Cape Fear River Basin and just west of the Atlantic Ocean makes it uniquely at risk for flooding from multiple sources, including natural sea level rise.

Out of 40 areas across the U.S., Wilmington experienced the biggest increase in "nuisance", or high tide, flooding days due to tidal changes over the past 70 years or so, according to a 2021 study from University of Central Florida researchers.

And in New Hanover County, 40% of properties have greater than a 26% chance of being severely affected by flooding over the next three decades, according to projections from First Street.

'Pick their poison'

Part of the challenge for planners – both in the southeastern U.S. and other fast-growing parts of the country - is a lack of developable land coupled with a population boom, even with the possibility of stronger hurricanes and storms.

Between 1996 and 2017, more than 10 new residences were built in North Carolina's floodplains for every property removed through government buyout programmes aimed in part at cutting flood risk, Hino and other researchers found in a study published last year.

New Hanover County's population grew by 11%, to about 225,000, between 2010 and 2020, compared to 7.4% growth for the country as a whole.

And with little developable land left, there are only so many places for new projects to sprout.

"This population growth is happening even in the face of additional flooding. We have had several hurricanes since (2016), and people are still moving here," said Rebekah Roth, planning and land use director for New Hanover County.

Lured by lower costs of living and amenities like proximity to water, people across the U.S. have migrated to areas most at risk of adverse climate effects like flooding, wildfires, and extreme heat, according to a 2023 study from the real estate company Redfin.

Daryl Fairweather, Redfin's chief economist, moved from Seattle, Washington to Wisconsin in the Midwest in 2020, partly to escape worsening wildfire smoke – only to run into the poor air quality that permeated much of the U.S. from record wildfires in Canada last year.

"There's no place in the country that doesn't have climate risk," Fairweather said. "I think people are just going to have to pick their poison (on) what climate risk they are willing to tolerate."

Terry Bragg, executive director of the Battleship North Carolina, is pictured on the ship across the Cape Fear River from downtown Wilmington in North Carolina, USA, February 29, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/David Sherfinski

Terry Bragg, executive director of the Battleship North Carolina, is pictured on the ship across the Cape Fear River from downtown Wilmington in North Carolina, USA, February 29, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/David Sherfinski

'Living with water'

Just down the river from Point Peter, the Battleship North Carolina – a World War II vessel and major tourist attraction - has launched a project known as "Living with Water" that will restore part of its parking lot to wetland habitat and elevate the rest.

At a kick-off ceremony several weeks ago, the parking lot flooded.

"It was a beautiful thing, you know," retired U.S. Navy Captain Terry Bragg, the site's executive director, quipped as he guided a tour on part of the ship.

"You could literally not walk directly from the parking lot into the visitors center because of the flooding. You had to scurry around (and) climb through the bushes - which was OK for messaging."

Other U.S. states are also eyeing new ways to adapt – including restrictions on where and how to build in risky areas.

After torrential rains devastated Vermont last year, state lawmakers have been working on legislation that would require a state permit to build near rivers.

And in Tennessee, lawmakers this month beat back an effort to unwind restrictions surrounding development in wetland areas.

For those areas and more coastal spots like New Hanover, time is running out. Burdette of the river advocacy group said that by 2050, the Point Peter site will be underwater.

"2050 sounds like a long way off, but it's not even a mortgage payment away. It's not even a generation away," he said. "It just seems so reckless to do it."

(Reporting by David Sherfinski; Editing by Zoe Tabary.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Extreme weather

- Adaptation

- Housing

- Loss and damage