‘We’ve lost so many lives’: Why LGBTQ+ refugees are giving up on Kenya

What’s the context?

Kenya was a haven for LGBTQ+ refugees but rising hostility is pushing some to extreme measures, like leaving for South Sudan

When Kevin was 20-years-old, he left his central Ugandan village and hitched a ride with a lorry carrying maize and beans towards the border.

The trans man decided to escape a stifling forced marriage in which he was expected to be a wife. Still presenting as a woman, he could not tell his husband, a family friend, who he really was.

Arriving at the border, Kevin hopped out of the truck and slipped into Kenya without a passport. He had heard that Kenya took in refugees, even if he did not know at the time that it was the only country in East Africa that has accepted people facing persecution for their sexual or gender identity.

But five years later, Kevin still lacks official refugee status in Kenya. Instead of freedom to express his true gender, he has found himself in a country where he feels as vulnerable as he was at home.

Speaking out about his situation puts him at further risk, which is why he’s using a pseudonym. But Kevin’s experience has made him determined to advocate for other LGBTQ+ asylum seekers in limbo.

“If I don't speak about the situation that we are going through, the rest of the world will not know that we are suffering,” Kevin told Context in Nairobi.

Kenya was once considered a haven for LGBTQ+ refugees in an otherwise hostile region, offering queer Ugandans relative freedom and rarely enforcing its own laws that criminalise same-sex relations.

Rights groups have long documented cases of homophobic abuse and discrimination that queer people regularly face. Now they worry they are being politically targeted, and that Kenya is not immune to the anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment that has spread across parts of Africa.

A Kenyan lawmaker put forth a bill inspired by Uganda’s prohibitions on same-sex activity, and nationwide protests against LGBTQ+ rights have erupted. The government’s refugee commissioner said last year being persecuted as an LGBTQ+ person is not grounds for protection in Kenya.

That has all left Kevin increasingly desperate to leave the country where he once hoped to begin a new life.

Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Influx from Uganda

Kenya has hosted queer refugees from Burundi, Sudan and Rwanda for more than a decade, but nongovernmental organisations say most new arrivals are from neighbouring Uganda, which in 2023 passed the Anti-Homosexuality Act, one of the world’s harshest laws targeting LGBTQ+ people.

Uganda first proposed anti-gay legislation in 2009, then known as the “Kill the Gays” bill for proposing executions for some same-sex activity, before international pressure forced it to step back. The current law intensifies colonial-era restrictions on same-sex relationships and again calls for the death penalty for acts of “aggravated homosexuality” and up to 20 years imprisonment for the “promotion of homosexuality,” which includes publishing pro-LGBTQ+ material or providing financial support to LGBTQ+ rights groups.

“In Uganda, they consider homosexuality to be a sin,” Kevin said. He was still a child when the first bill was being debated and saw the vitriol unleashed. In 2010, a tabloid published the names of 100 people it alleged were gay and featured photos of the accused on its cover with the phrase, “Hang them.” The following year, prominent LGBTQ+ activist David Kato, whose photo was on the cover, was killed.

The climate prompted LGBTQ+ Ugandans to head to Kenya. While there are no official figures on how many LGBTQ+ refugees Kenya hosts, in 2021 the UNHCR, the U.N.’s refugee agency, estimated 1,000 were in the country. Most rights groups say the figures are likely higher today. The UNHCR was not able to provide Context with an updated figure.

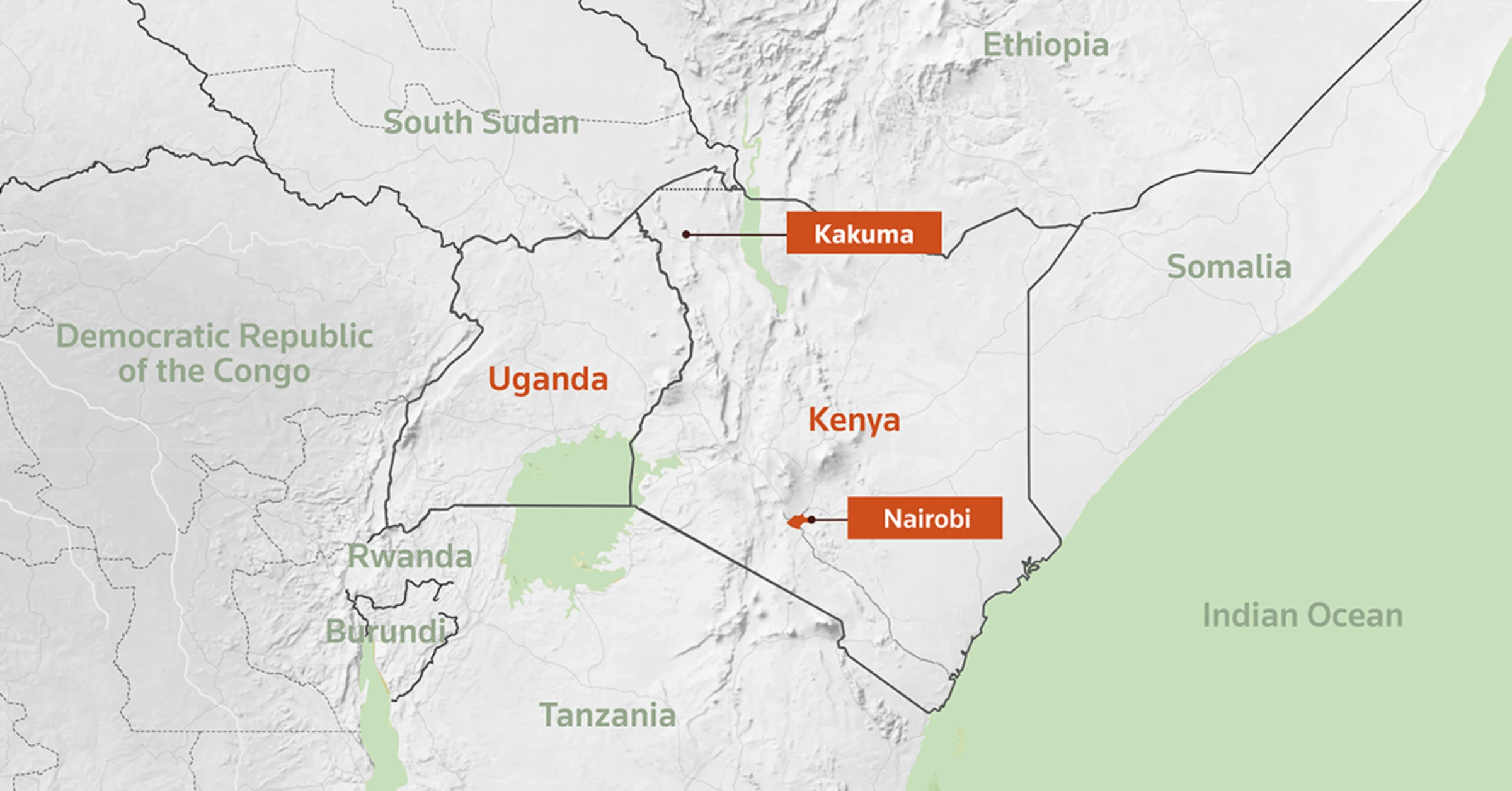

Kevin first tried to settle in the capital Nairobi, but Kenya’s policy of housing asylum seekers at camps required him to move 800 km (500 miles) away, near the Ugandan border.

'People have trauma from Kakuma'

Like most other LGBTQ+ asylum seekers from Uganda, Kevin ended up in the Kakuma refugee camp. Meaning “nowhere” in Swahili, Kakuma is the size of a small city, home to more than 298,000 asylum seekers and refugees in northwest Kenya.

This is where they wait while the government decides whether they will officially be deemed refugees — a status that allows them to work, open a bank account, get a SIM card and leave the camp.

Instead of finding safety, Kevin said he was the target of escalating abuse at Kakuma. He was beaten, and his monthly food rations were often taken from him by other refugees. In June 2020, other refugees coordinated an attack on LGBTQ+ asylum seekers, including setting fire to their shelters. One LGBTQ+ person has been killed at the camp, and suicide took at least one other life.

“People have trauma from Kakuma — we've lost so many lives, people run mad (from) the situation that we went through,” Kevin said.

His experience mirrors testimony from dozens of other LGBTQ+ asylum seekers previously interviewed by Reuters and NGOs.

In a 2023 report, Amnesty International and the Nairobi-based National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (NGLHRC) compiled interviews with LGBTQ+ refugees in Kakuma and found that 31 out of 38 interviewees had experienced threats and attacks, including rape, stabbings and having their shelters set on fire at the camp.

Kevin is one of dozens of asylum seekers who have reported being the target of escalating abuse at the Kakuma refugee camp, including fire being set to their shelters. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Kevin is one of dozens of asylum seekers who have reported being the target of escalating abuse at the Kakuma refugee camp, including fire being set to their shelters. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

A 2021 survey carried out by the Organization for Refuge, Asylum and Migration (ORAM) and the North America-based Rainbow Railroad, which assists LGBTQ+ people relocate to safety, found 83% of 58 respondents had experienced physical assault and 26% reported sexual assault at Kakuma.

In April 2020, Reuters reported that a group of about 300 gay, lesbian and transgender people living in Kakuma said other refugees repeatedly attacked them because of their sexual orientation.

Reporting attacks to the authorities has largely proved ineffective, with Amnesty documenting only a single case that was investigated by police in its 2023 report.

“They say that the police (are) there to protect you,” said Kevin. “But the fact is, the police are the number one homophobic people in the camp.” The National Police Service did not respond to a request for comment.

The sustained and intense nature of the violence and lack of a sufficient police response led Amnesty and NGLHRC to conclude that “the Kakuma refugee camp complex is not safe for LGBTI asylum seekers and refugees.”

As far back as 2018, the U.N. refugee agency UNHCR relocated 200 asylum seekers to Nairobi after violent attacks and temporarily stopped registering newcomers to the camp, according to the Amnesty report.

But relocations and expedited applications have become rare, according to advocates and asylum seekers.

These decisions are ultimately authorised by the Kenyan government and made on a “case by case” basis, said Dana Hughes, a UNHCR spokesperson based in Nairobi. She also said the agency is making “every effort to ensure” LGBTQ+ refugees are protected.

LGBTQ+ cases 'kept on hold'

The government previously told Context that the average wait time is 12 months for an asylum application. But seven asylum seekers told Context they have been waiting up to six years. And many thought their cases were either being deliberately delayed or not processed at all.

The Department of Refugee Services did not respond to multiple phone calls and emails, nor a written request submitted in person, asking for an interview.

When the country’s refugee commissioner John Burugu was asked about this issue at a refugee-led NGO conference in August, he responded that persecution based on “those letters” — referring to the acronym LGBTQ+ — were not valid grounds to seek asylum.

Burugu reiterated his position in a September interview with Context. "We are not interested in anyone's sexual identity,” he said. “It will not be a measure of convincing us to admit someone who fails to meet the threshold of being admitted as a refugee."

Any asylum seeker who meets the legal definition set by Kenya's 2021 Refugees Act would be granted protection after due process, Burugu said. That legislation considers refugees to be people fleeing foreign aggression or facing persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a social group.

Although persecution for being LGBTQ+ is not explicitly covered by the regulation, they were previously considered “at risk,” according to the Amnesty report.

While the UNHCR told Context it is not aware of an official change on who qualifies for asylum, it has seen delays in claims by LGBTQ+ people in recent years.

“In the past asylum-seekers with claims of this nature were normally recognised as refugees,” Hughes wrote in an email.

“However, since 2021, UNHCR has observed that such claims have been increasingly kept on hold without a decision being made.”

Hughes added that the backlog of 219,000 overall asylum cases was also a factor in the slow processing and that since October 2024 “considerable progress” had been made.

Kenya hosts one of the world’s biggest refugee populations, with more than 823,000 asylum seekers and refugees registered in the country. Eighty-seven percent of them are at the Dadaab camp in the southeast and at Kakuma, and the remainder live in urban areas.

Victor Nyamori, an Amnesty researcher in Nairobi who worked on the Kakuma report, acknowledged that Kenya is grappling with a large number of claims, but said he believes other factors are at play when it comes to LGBTQ+ refugees. “We indeed know these processes are being delayed and from the statements of Burugu … it really firms up some of the fears that are in the community,” he said.

Hiding in Nairobi

Under attack and losing hope that a refugee status appointment will ever happen, many queer asylum seekers do something that could hurt their cases: leave Kakuma.

Asylum cases are typically only handled where asylum seekers are assigned to live, and being away for longer than two weeks can land an asylum seeker in legal trouble, potentially leading to detention, said Nyamori.

About a dozen or so discreet shelters have popped up in Nairobi to house queer refugees, often on the outskirts of the city, where residents hide from both police and nosy neighbours.

Being outed can have severe consequences, such as police harassment, rights groups warn. The NGLHRC noted in a 2021 report that “there have been quite a number of cases of police raids and arbitrary arrests in a number of refugee safehouses.”

Three refugee shelters visited by Context all confirmed this was an ongoing issue. Ronnie, an asylum seeker from Uganda, helps run one of these shelters in the outskirts of the city.

The shelter is behind a high wall and locked metal gate; inside is a small home with a kitchen, shared living area and gender-segregated bedrooms. It shares a plot of land with a midrise building that Ronnie is wary of, so he asks newcomers to keep a low profile.

“We've been raided four times by the police,” he said.

Ronnie lives in one of the dozen or so discreet shelters have popped up in Nairobi to house LGBTQ+ refugees. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Ronnie lives in one of the dozen or so discreet shelters have popped up in Nairobi to house LGBTQ+ refugees. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Ronnie, 28, is bisexual and left Uganda six years ago, and only feels comfortable using his first name. Like many others, he fled Kakuma.

He moved to Nairobi, where he felt he could make a life for himself. “I have my two hands. I can survive, I can work, I can cook and sustain myself,” he said.

Trained as a cook, Ronnie had hoped to work in Kenya’s booming hospitality industry but instead runs a small catering business because he cannot legally work in a hotel kitchen.

Kenya’s informal economy is dominated by micro businesses such as Ronnie’s. A 2019 International Labour Organization report estimated just over 80% of Kenya’s workers were in the informal economy.

ORAM has provided training for more than 500 asylum seekers to start their own enterprises.

“Financial assistance is not sustainable, and therefore we need solutions for individuals to make use of their own skills,” Winfred Wangari, who manages ORAM’s East Africa programme, said in an interview in Nairobi.

Ronnie was given seed money from the NGO for his catering business, which he hopes to expand to train more refugees.

But after waiting years for refugee status, he now wants to leave Africa.

“No one can be strong for six years,” said Ronnie. “Waiting that long has made me lose hope.”

Threadbare tolerance

In Kevin’s third year at Kakuma, he was finally granted an appointment to determine his status. But he left the camp before receiving a decision, after advocating — and ultimately failing — to secure better conditions for LGBTQ+ asylum seekers.

Kevin was part of a group that repeatedly protested outside the UNHCR’s offices, including a three-day sit-in that was dispersed by police using tear gas. Like Ronnie, he lives in hiding in Nairobi, while he is still registered at the camp.

To learn what stage his application has now reached would mean returning to Kakuma, an expensive journey to a place where he feels unsafe.

Kevin, an LGBTQ+ asylum seeker, received support from ORAM to start a barber shop in Nairobi, Kenya. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Kevin, an LGBTQ+ asylum seeker, received support from ORAM to start a barber shop in Nairobi, Kenya. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Kevin also received support from ORAM to start a barber shop. His business partner does not know he is trans, and he presents as a woman at work. The intolerance he had hoped to leave behind in Kakuma was not confined to the camp, he has learned.

A threadbare tolerance for LGBTQ+ people in Kenya may be at a breaking point. The Family Protection Bill, has not yet gone before parliament, but a draft seen by Reuters introduces the death penalty for "aggravated homosexuality," which includes gay sex with a minor or disabled person or when a terminal disease is passed on.

It has coincided with a disheartening series of events for rights campaigners. In 2019, the country’s highest court upheld a colonial-era law criminalising same-sex relations. When another court decision affirmed the freedom to associate for LGBTQ+ Kenyans in 2023, protesters took to the street.

Prominent Kenyans like first lady Rachel Ruto have said LGBTQ+ Kenyans are threatening family values. Activists say this type of scapegoating is a regular occurrence, pointing to examples like AI images flooding social media that claimed queer people fueled last year’s anti-government protests.

After waiting five years for official documentation, the promise of settling in Kenya is more bitter than sweet for Kevin.

“Staying in a country where you face homophobia, in a country where you're not free to do (what) you want to do — even if I get (refugee status), it won't make any use,” Kevin said. “I’m not free to be who I am.”

Fleeing to another ‘dire’ camp

He is now considering an extreme idea: leaving Nairobi for Juba, the capital of South Sudan, which is in the throes of one of the world’s most severe humanitarian crises as it hosts a half-million refugees from war-torn neighbouring Sudan.

Hughes described the conditions at the Gorom refugee camp in Juba as “extremely dire.” It houses more than five times the number of people the camp was built for.

But his experience at Kakuma has coloured Kevin’s view — he thinks Gorom may provide a better chance at eventually reaching Canada or the United States.

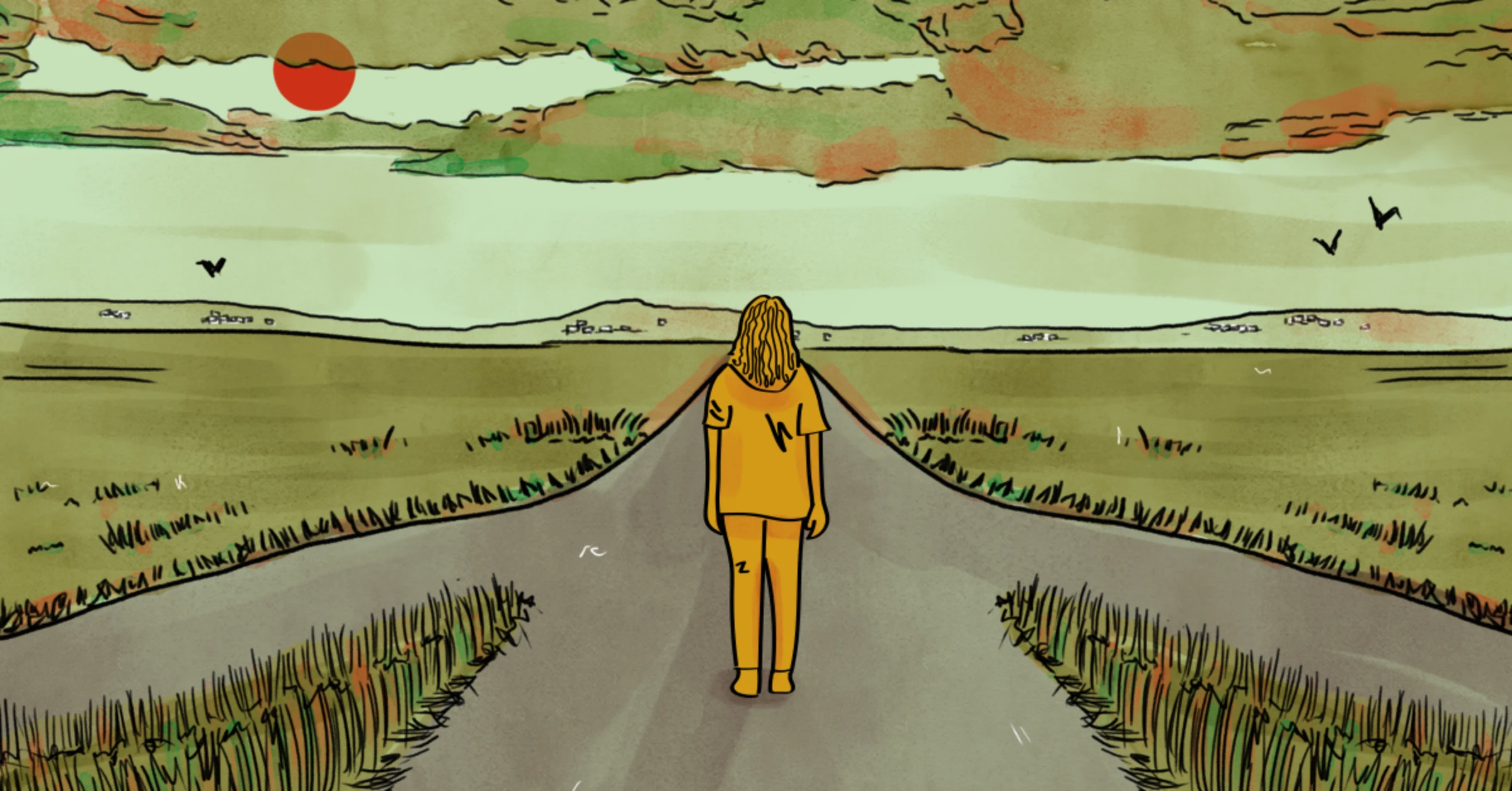

Kevin is still deciding whether he will leave Nairobi to make the journey to Juba, South Sudan. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Kevin is still deciding whether he will leave Nairobi to make the journey to Juba, South Sudan. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

“Almost everyone who was in Kakuma has gone (to South Sudan) this year,” said Kevin.

The Canadian Press cited the UNHCR as saying that 450 LGBTQ+ asylum seekers from Kakuma have arrived in Juba since January 2024, and that 28 people have been resettled in the United States. The UNHCR confirmed these numbers were accurate as of December.

Devon Matthews, head of programmes at Rainbow Railroad in Toronto, said it is up to refugees themselves to decide what is best for them, but there are challenges for those heading to South Sudan, including resetting the clock by entering in a new queue to be considered for resettlement.

Matthews said there is evidence of some recent progress in LGBTQ+ asylum cases in Kenya, but that the “Kenyan government is outwardly and earnestly homophobic.” For those without an advocate or organisation supporting them, people can “get lost in the system,” she said.

“We resettled a trans woman who was in Kenya for 13 years recently, who had been stuck in an endless loop of bureaucracy,” Matthews said.

For now, Kevin remains unsure whether he will attempt the route through South Sudan, but he is encouraged by seeing other LGBTQ+ asylum seekers from Kenya in Gorom.

“When you're alone, it's always hard,” Kevin said. “But when you're many, you can find a way of surviving.”

This story is part of a series supported by Hivos's Free To Be Me programme.

Reporting: Sadiya Ansari

Additional reporting: Enrique Anarte-Lazo and Jackson Okata

Editing: Ayla Jean Yackley and Barry Malone

Graphics: Karif Wat

Production: Beatrice Tridimas

Tags

- LGBTQ+