US schools teach 'media literacy' to fight online disinformation

Michael Spikes teaches a 2012 training on media literacy in Washington, D.C. Donna Walker/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

What’s the context?

Eighteen U.S. states now mandate the teaching of "media literacy" in public schools to tackle growing online disinformation

- Jan. 6 attack on U.S. Capitol driving efforts

- Dozens more bills underway

- Advocates want issue taught across curricula, age groups

WASHINGTON - When Braden Hajer was a high school freshman in Illinois, he almost lost a friend to the internet.

"It was ugly. He was sort of ping-ponging around some of the most ridiculous, extreme ideologies, pulled into more and more niche corners of the internet," Hajer told Context.

He recalled the friend espousing conspiracy theories about, for instance, Jews controlling the education system – and shouting matches in the lunch room.

"It nearly broke every friendship he had," recalled Hajer, now 20.

At first, Hajer blamed a lack of content moderation from social media platforms, but later started to think "maybe we should be giving students the tools to deal with the rhetoric" they encounter on the internet.

The friend subsequently recovered from his internet-driven conspiracy obsession, but during his senior year Hajer used the experience to try to require such tools, culminating in a state law that this school year began mandating the teaching of "media literacy" in public schools.

It is part of a wave of state actions around media literacy in reaction to new recognition of the potentially ill effects of social media – including, Hajer said, the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol by supporters of then-president Donald Trump.

"That moment highlighted for a lot of people a side of the internet that they hadn't considered could manifest itself into real, physical, dangerous action," he said. "I don't know if the bill passes without January 6."

Eighteen states now have some kind of media literacy education requirement in law, according to a March report from Media Literacy Now, an advocacy group.

The group says it is also tracking dozens of related bills but warns that action is "still too slow compared to the urgent and immediate need".

"This is 21st-century literacy," said Erin McNeill, the group's president and founder.

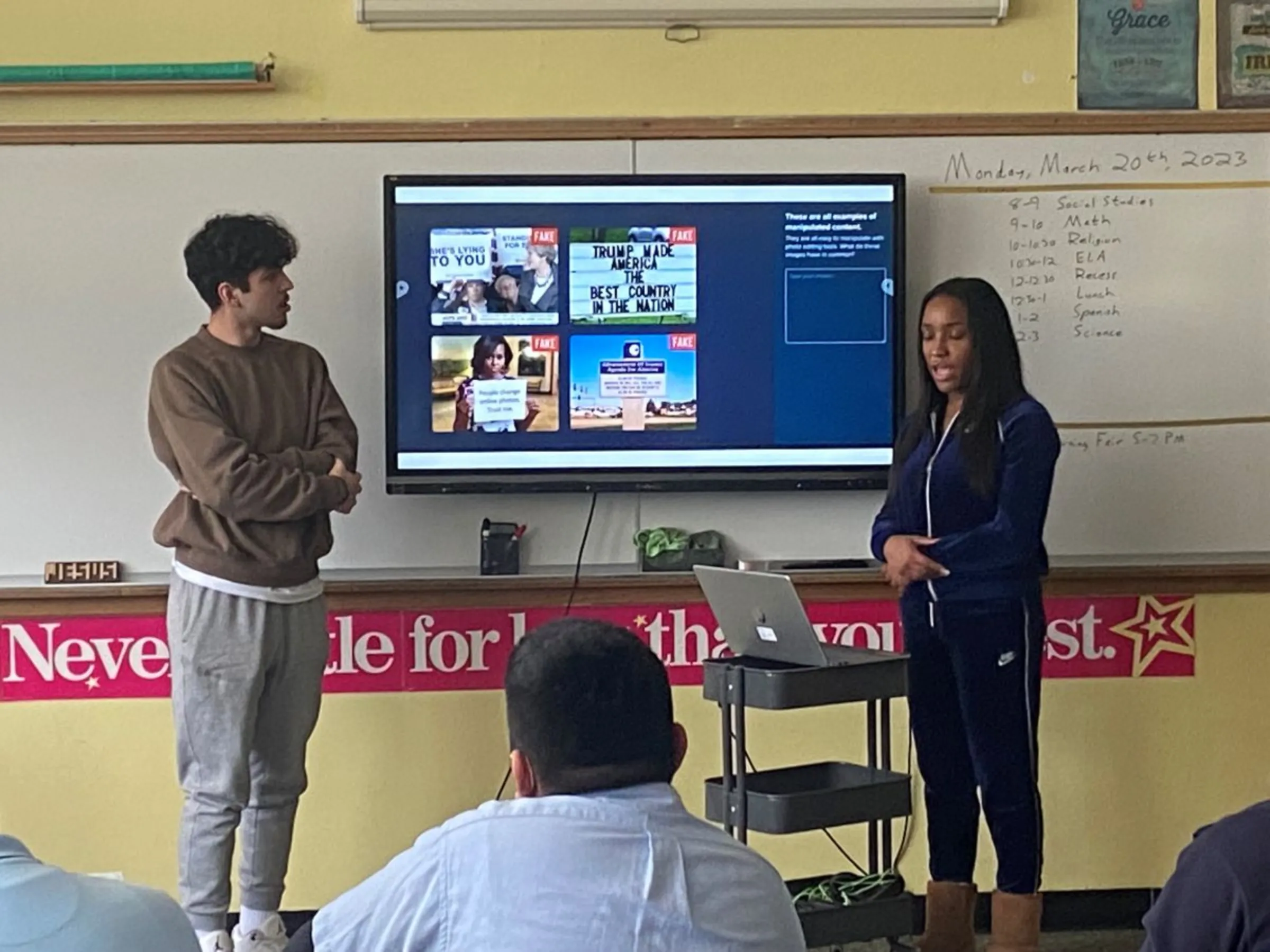

Students in Chicago take part in a media literacy class in February 2023. Anne-Michele Boyle/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Students in Chicago take part in a media literacy class in February 2023. Anne-Michele Boyle/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Youth survival skill

The focus on media literacy comes amid a broader reckoning over the civic and health dangers posed by social media, heightened during the pandemic.

In April, the American Psychological Association released a health advisory on social media use among adolescents, recommending that any such use be "preceded by training in social media literacy", including to help users question the accuracy of content, recognize racist messages and more.

U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy published a similar advisory in May, and urged support for media literacy in schools.

Companies including Google, Meta, Twitter and TikTok did not respond to requests for comment on rising policymaker interest in media literacy.

NetChoice, an industry coalition that includes Google, Meta, Twitter and other tech firms, declined to comment.

In January, New Jersey became what it said was the first state to create an "information literacy" mandate for kindergarten through 12th grade, which Governor Phil Murphy said was a response to "the proliferation of disinformation that is eroding the role of truth in our political and civic discourse".

The state Education Department is now working up a curriculum.

"Students are so used to using their phones for things – they can use Google and other sites, but they don't really know how to interpret what they're seeing," said Sharon Rawlins, a youth services specialist with the New Jersey State Library.

But in addition, Rawlins said, "parents need to be informed – information literacy is important for them because they need to help their children navigate (online). They may also be looking for jobs."

That means a significant potential role for public libraries, said Mimi Lee, the State Library's director of literacy and learning: "Literacy is what we do as libraries."

Others go still further – Representative Jim Murphy, a Republican state lawmaker in Missouri, calls media literacy a new survival skill.

"Kids by the time they're about 10 have been exposed to more media than I have been exposed to in my 72 years," he said in a phone interview. "The parents don't know how to go after this or even teach them, because they were never brought up in this world."

Murphy has been spearheading a push in his state for a media literacy requirement for the past five years, and says he is getting closer despite minor pushback.

Some see media literacy as "about indoctrinating our kids about one political view or another. But it's not about content but about how to process – and if we can do that, I think the whole world will be better."

Legislating against social media sites themselves would be fraught, Murphy said, given constitutional rights around free speech and more.

"I'd rather teach our children to be better receivers than to try to restrict those that are sharing the information."

Students in Chicago take part in a media literacy class in March 2023. Sean Brown-Coley/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Students in Chicago take part in a media literacy class in March 2023. Sean Brown-Coley/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

How do you teach media literacy in school?

The U.S military is starting to take steps to teach media literacy, as well, with several branches last year releasing new strategies.

And governments elsewhere are likewise putting in place mandates on the subject, with Finland in particular being lauded for teaching the subject across multiple subjects and "from daycare on up", according to a government website.

With media literacy requirements now getting into U.S. lawbooks, backers say the next step will be to follow a similar strategy – trying to expand those efforts to cover many ages and classes.

"I would like to see this in all subject areas," said Michael A. Spikes, a lecturer at Northwestern University's journalism school who is involved in implementing the new Illinois law.

"We've heard from teachers who have started to talk about it as part of mathematics, in terms of understanding statistics and polls. Or in science – there are lots of opportunities around understanding what is a research study."

Anne-Michele Boyle, who teaches high school students in a Chicago public school, said the legislation is already prompting a rise in the resources available to teachers on the subject.

Her classes already included some focus on media literacy, but she was prompted to scale up significantly after the Jan. 6 attacks on the Capitol.

"I canceled my lesson plans for February, cobbled together resources, and spent the whole month of February ... teaching media literacy skills," she recalled.

Since then, Boyle has developed a unit that spans five to six weeks, helping students gauge bias, assess credibility and detect disinformation, and learn skills such as reverse image searches.

"I hope to see an extracurricular club at our school emerge next school year, for students that want to be media literacy advocates all year long," she said.

"I am already hearing some buzz about this idea!"

(Reporting by Carey L. Biron, Editing by Zoe Tabary)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Digital Divides

- Education

- Future of work