The air conditioning dilemma: Cooling homes heats the planet

A man looks at air conditioners outside a discount electronics store at a shopping district in Tokyo, Japan, April 28, 2015. REUTERS/Yuya Shino

What’s the context?

Demand for AC is rocketing as heat waves intensify, but it also contributes to global warming.

LONDON - As temperatures soar around much of the world, people are cranking up the air conditioning, but blasting icy air into buildings fuels global warming, which increases demand for more cooling, creating a vicious circle.

Climate change, rapid urbanisation, rising incomes and population growth are driving huge demand for air conditioners (AC) globally, but particularly in developing countries.

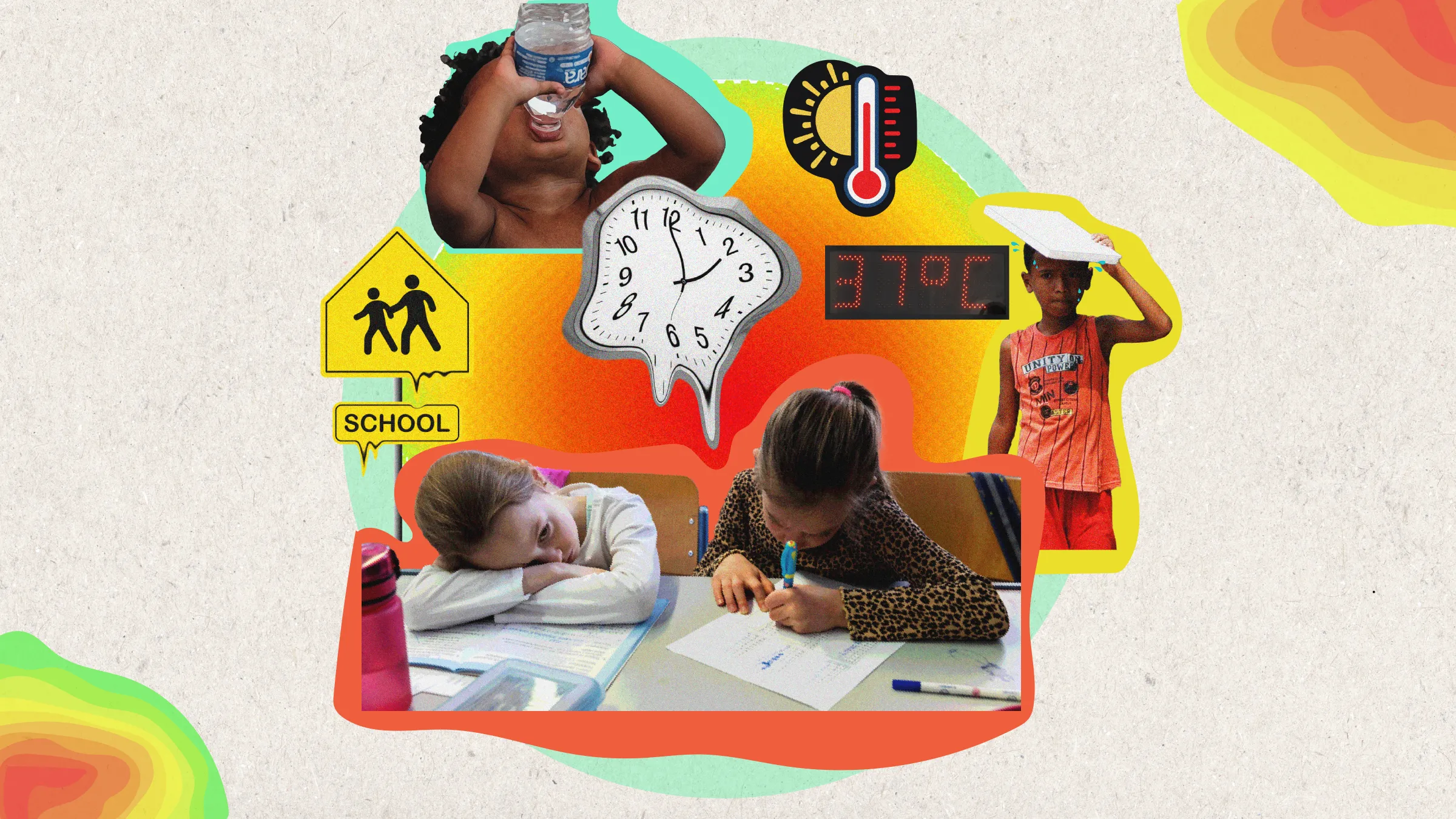

Access to cooling is crucial for health, reduces heat-related deaths, helps children study in school and boosts workers' productivity.

But air conditioning's high energy consumption and impact on the climate is often overlooked.

Without swift action, planet-warming emissions from cooling - ACs and refrigeration - could account for more than 10% of total emissions by 2050, according to the U.N. environmental agency UNEP.

For comparison, aviation currently accounts for about 2.5% of global CO2 emissions.

How fast is demand for air conditioning rising?

Demand is set to treble by 2050, compared with 2016, according to projections by the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The fastest growth is predicted in Africa and South Asia. India could have about 1 billion units by 2050, more than 10 times the number today, IEA forecasts suggest.

But even cooler countries like Britain, where residential AC is uncommon, have seen sales soar, according to media reports.

How do air conditioners cause climate change?

Air conditioning guzzles electricity. Much of this comes from burning fossil fuels, which releases heat-trapping CO2.

It also uses refrigerants which have a global warming potential hundreds or even thousands of times greater than CO2. Nearly 40% of residential AC emissions are due to refrigerants, according to UNEP.

In built-up areas, air conditioners can exacerbate the urban heat island effect as they expel warm air into city streets, potentially raising temperatures by more than 1 degree Celsius at night.

Residents in densely populated Hong Kong report switching on their air conditioning because neighbouring AC units blow hot air into their apartments.

Can we make air conditioning greener?

The good news is that manufacturers are developing increasingly energy-efficient models and smart tech can ensure AC units do not unnecessarily cool empty rooms and offices.

Scientists are also innovating less polluting refrigerants and even new AC technologies that do not need refrigerants.

In 2021, two AC companies won a global competition supported by India's government and non-profits to produce prototypes for residential units with five times less impact on the climate than standard models.

However, producing ultra-efficient ACs at an affordable price remains an issue, and they are not yet commercially available.

How can we cut emissions from air conditioning?

Scores of countries have signed a Global Cooling Pledge, which calls for cooling-related emissions to be cut by at least 68% by 2050 over 2022 levels.

UNEP's Cool Coalition, which instigated the pledge, is urging countries to prioritise passive cooling measures, improve energy efficiency and accelerate the reduction of climate-warming refrigerants.

Good building design incorporating passive cooling measures like insulation, natural ventilation and shading can dramatically reduce air-conditioning needs. Planting trees also lowers temperatures.

High-tech passive cooling innovations include solar-blocking smart glass and paints which radiate heat back into space.

Some cities like Dubai, Doha, Paris and Munich have adopted district cooling, which involves piping chilled water into multiple buildings such as offices and commercial premises.

Do we need to change attitudes towards air conditioning?

Behavioural change is an important part of the picture.

Many people see air conditioning as a status symbol, even though using passive cooling measures along with fans or air coolers can be enough to keep temperatures comfortable and is much cheaper.

Some cities like Hong Kong also whack air conditioning so high that residents need warm clothes at the height of summer.

But attitudes are beginning to change.

Singapore launched a national campaign this year called "Go 25" to encourage residents to set AC temperatures in homes and offices to 25 C or higher to conserve energy.

In Taipei, businesses risk fines if they cool rooms to below 26 C.

India is considering setting the lowest temperature on new units to 20 C.

Switching to more energy efficient AC units would also slash energy consumption - and CO2 emissions. Globally, the average new air conditioner sold is about half as efficient as the best available, according to the IEA.

Governments can drive change by introducing stricter energy performance standards, clear labelling to help consumers choose more efficient models, incentives to lower costs and regulations to deter the dumping of old, polluting units in developing countries.

(Reporting by Emma Batha; Editing by Ellen Wulfhorst.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Extreme weather

- Energy efficiency

- Energy access