What’s the context?

A clandestine network smuggling sanctioned oil around the globe has lured thousands of seafarers into dangerous jobs.

NEW YORK - When the crew on board a small fishing vessel off of Dubai saw a coast guard speedboat racing through the darkness, they prepared for the worst, hoisting an iron shield on the bridge in an improvised attempt to guard against potential gunfire.

Their vessel, the Meigou-4, sailed from Iran to United Arab Emirates waters every day to meet another boat with a motorised hose pipe to draw out its cargo of Iranian fuel. This process, known as ship-to-ship transfer, is a fundamental part of a vast smuggling network that generates tens of billions of dollars in revenue each year.

Shubham Singh, a 23-year-old Indian seafarer on the Meigou, did not know he would be involved in the transportation of sanctioned Iranian diesel when he was recruited in late 2020 for what he believed was the next chapter in a promising career at sea.

Four months later, he was staring at the lights of a fast-approaching coast guard vessel, terrified he would face imprisonment - or worse, if shots were fired.

“After discovering the illegal fuel smuggling operation, I was trapped at sea with no internet,” Singh said in an interview over WhatsApp. “My only solace was prayer, hoping nothing would happen to me.”

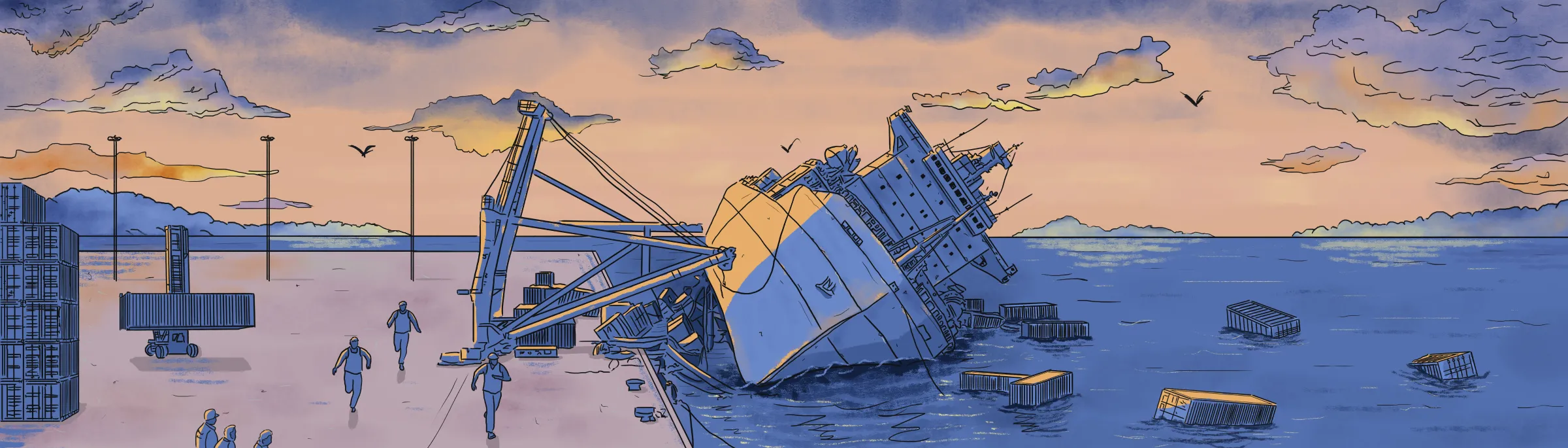

Hundreds of seafarers risk their lives manning the dark fleet, facing dangerous working conditions and low wages. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Hundreds of seafarers risk their lives manning the dark fleet, facing dangerous working conditions and low wages. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

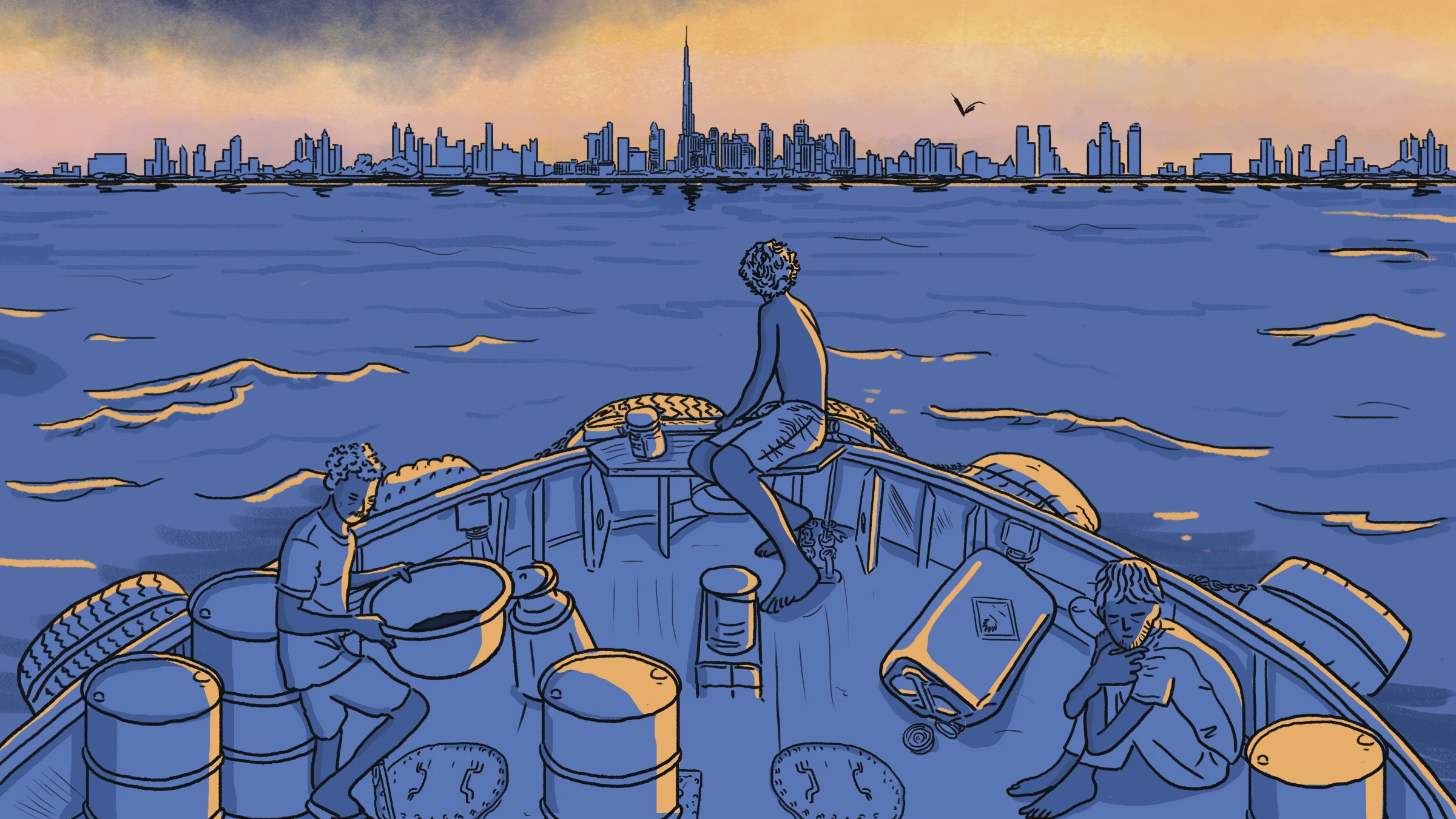

As the spikey silhouette of the world’s tallest building, the Burj Khalifa, shimmered in the distance, the crew watched the coast guard sail past their boat, apparently undetected.

Singh’s account of his close brush with danger offers a rare insight into the perils faced by a growing number of seafarers who are lured into working on vessels that carry sanctioned oil around the globe.

Efforts by countries like Russia and Iran to circumvent Western sanctions on their petroleum industries have helped spawn a black market at sea, leading to a surge in human rights abuses of the seafarers recruited into the dangerous world of the shadow fleet.

About 17% of global oil tankers are estimated to be part of the shadow or dark fleet - ships with murky ownership and little or no insurance that often evade surveillance, many of them used to deliver sanctioned oil to an energy-hungry world.

The fleet is believed to have expanded by 45% in the last year alone after the United States introduced new punitive measures against Russia over its war in Ukraine.

“There are unintended consequences of sanctions,” said Cormac Mc Garry, who leads Control Risks' maritime intelligence and security services in Paris. “All these new problems have been created by Russia and Iran trying to get around the sanctions.”

Go deeper: What is dark shipping, and why is it dangerous?

‘Shadow economy’

For decades, the United States and its allies have waged an economic battle against Iran over its nuclear programme and support for militants in the Middle East by banning oil sales, blocking access to the global banking system and barring foreign investment in its energy sector.

The 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action had provided Iran with temporary relief from these sanctions. But President Donald Trump withdrew from the agreement in 2018, crippling Iran’s ability to legally export oil, the lifeblood of its economy.

Western nations also imposed sanctions on Russia in 2022 to limit its ability to finance the war against Ukraine. These include prohibitions on providing insurance, shipping and financial services for oil exports above a maximum price of $60 a barrel.

In response, Russia and Iran have developed a clandestine trade in sanctioned oil products. While major buyers include China, India and Turkey, countries in the European Union have also helped keep Russian oil flowing by buying products from Indian refiners.

The Iranian government did not respond to a request for comment.

Other oil-producing nations under sanctions include Venezuela and Libya.

The illicit cargo is transported around the globe by a shadow fleet of ships that turn off or manipulate their marine navigation systems to avoid detection, which violates the International Maritime Organization’s safety at sea convention.

“Western sanctions on Iran and Russia have clearly failed to shut down the Iranian and Russian petrostate economies,” said Mc Garry. “Now we have a shadow economy for Russian and Iranian oil and gas products, and as a result, the shadow fleet.”

Sanctions also target companies that enable the trade, including UAE and Hong Kong oil brokers and ship management firms in India and China. Individual tankers that the U.S. government has determined are trading in sanctioned oil can face penalties.

“One goal of sanctions is to potentially drive these guys out of business. But we see replacement of dark fleet vessels all the time,” said David Tannenbaum, director of Blackstone Compliance Services, a Washington-based consultancy that helps financial institutions meet anti-money laundering and sanctions rules.

“One vessel gets sanctioned, and the shipowners will just buy a new vessel,” he said.

Every ship must fly the flag of the country where it is registered and abide by its rules. But dark vessels may fraudulently claim registration or fly a flag of convenience, the practice of registering in a country with lax regulations.

Vessels in the shadow fleet are usually old and in various states of disrepair.

“Dark ships typically don’t have insurance, they manage to avoid inspections, they work between ports that they’re never going to get hassled at,” said Cris Partridge, managing director of Myrcator Marine & Cargo Solutions FZE, a maritime consultancy in the UAE.

Operating beyond the reach of the law, the size of the dark fleet is difficult to determine.

Singapore-based Trafigura, the world’s second-largest private oil trader, estimated in February 2023 the shadow fleet included about 400 crude oil and 200 oil product tankers globally.

The London-based energy intelligence firm Vortexa said that 1,649 tankers had operated in the “opaque market” between January 2021 and November 2023, and that 75% of the vessels transported oil products from Russia, Iran and Venezuela.

Go deeper: How shipping's flags of convenience endanger seafarers

Rogue recruiters

Finding the manpower to sail ships skirting international law is a hurdle for businesses operating in the shadow network.

Unscrupulous shipping companies prey on inexperienced, impoverished jobseekers who are more likely to accept positions with dangerous working conditions and low wages, said Chirag Bahri, operations manager at the International Seafarers' Welfare and Assistance Network (ISWAN), which provides assistance to seafarers in distress.

“There is a correlation between illicit recruitment and ships transporting illicit cargo and drugs,” Bahri said. “They want crew from cheaper countries where they don’t have full protection of their rights. They look for countries that have lenient rules and laws.”

Some recruiters even resort to human trafficking to staff crews, targeting vulnerable people and trapping them on ships engaged in dangerous or illegal activities.

These seafarers are forced to work for little or no pay. Far away from home and cut off from phones and the internet, they are unable to sound the alarm to their abuse, seafarers interviewed by Context said.

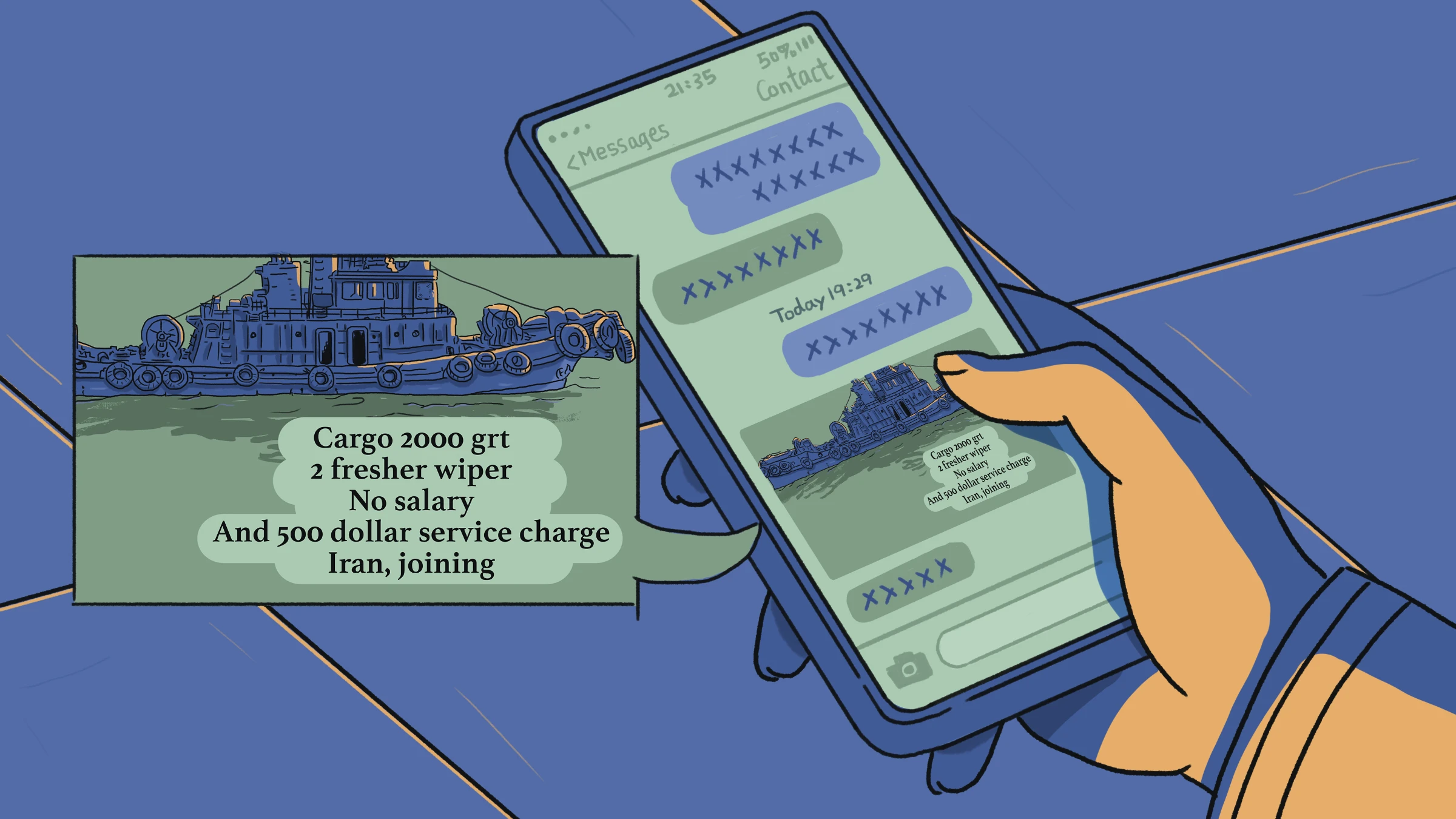

WhatsApp groups advertise roles targeting inexperienced jobseekers, often without salaries, promising a fulfilling career. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

WhatsApp groups advertise roles targeting inexperienced jobseekers, often without salaries, promising a fulfilling career. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

“Some of my friends went to Iran a few years ago and faced many problems: no salary, always hungry, no rest and being made to work for many months longer than their contracts stated,” one Indian seafarer told Context on condition his name was not used.

India is a major source of seafarers recruited to the shadow fleet, in part because of its relative proximity to Iran and the diplomatic and trade links between the two countries.

“India is the bedrock of abuse, scams and illegal fees,” said Steve Trowsdale, inspectorate coordinator at the International Transport Workers' Federation (ITF). “They’re told their child will earn in U.S. dollars. Then the family gets excited. They get lured by fake promises.”

Recruiters tour the Indian countryside looking for potential targets in poor villages or post job listings on social media, without fully disclosing to which country seafarers will be sent, said Bahri.

While it is difficult to ascertain how many Indian seafarers are trafficked, ISWAN and the ITF estimate several hundred cases occur each year.

Context gained access to two WhatsApp messaging groups used by seafarers trafficked to Iran - each with around 250 members.

Job advertisements were also distributed in WhatsApp groups, with salaries of as little as $200 per month or no payment at all, touting the work as career-boosting experience.

Some of the postings stipulate a “service charge” of as much as $500 be paid by applicants to be considered for work - a practice the International Labour Organization (ILO) says can lead to debt bondage, trapping workers in forced labour to repay their recruitment debts.

Go deeper: Q&A: Palau pledges cleanup of abuse-riddled ship-flagging system

Selling a dream

Singh found himself ferrying Iranian crude across the Persian Gulf after falling victim to such a pay-to-work scheme.

Singh, who trained at Commander Ali's Academy of Merchant Navy near the Indian city of Hyderabad, had already begun his seafaring career, completing a single contract in Vietnam.

He was looking for his next assignment when a recruiter in Goa state introduced him to another agent who was only identified as Sumit.

At a recruitment agency’s office in Mumbai, Sumit offered Singh a career-building job on board a large bulk vessel in Iran - at a price. Singh had to pay 250,000 rupees, worth about $3,370 in 2020, to work for Sumit’s contact in Iran.

Young men like Singh, desperate for a fulfilling career and income to support their families, are easy targets for recruiters selling promises of a better life, said Bahri.

“Families have a dream that their child will help them to move out of poverty,” he said. “But they fall prey to notorious agents that promise training, documents and a job aboard a ship.”

Once their loved ones have been entrapped, there is often little that families back home can do to help.

Bahri has handled cases where families are pressured to withdraw criminal complaints about their sons’ exploitation by agents who claim to have the police in their pockets. “Some agents have also said, ‘I've already paid money to the police … Nobody can touch me,’” he said.

The Indian government did not provide responses to the claims of police misconduct or other allegations raised in this article.

About a quarter of a million Indians work on the world’s 100,000 or so merchant vessels, accounting for almost 10% of the seafaring workforce, making them the third-largest nationality in the industry, after Filipino and Chinese seafarers.

But the ITF reported that Indian seafarers faced the highest number of ship abandonments in 2024, the worst year on record for the practice.

The ITF defines ship abandonment when a crew’s salary is unpaid for at least two months, though members can be stranded for months or even years, often without adequate food, water or fuel.

As vessels in the dark fleet operate illegally, it's difficult to determine their size. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

As vessels in the dark fleet operate illegally, it's difficult to determine their size. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

“I imagine recruiters will go for people who are easy to abuse. The shadow fleet is at more risk of non-profitability or detainment by a state, such that the owners would be more willing to abandon them,” said Mc Garry.

Indian authorities have been slow to intervene when their citizens are stuck on abandoned ships or face criminal charges for the wrongdoing of their employers, according to the ITF.

India is a signatory of the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC) of 2006, an international seafarers’ bill of rights, and has tasked its Directorate General of Shipping with regulating the sector, including oversight of seafarer recruitment. Only licensed agents who do not charge placement fees are permitted to operate.

But industry observers say India’s enforcement of seafarer protections is weak.

“India has ratified the MLC, which means they must maintain a list of registered recruitment agents,” said Trowsdale. “They have got a list, but the Indian government and (shipping directorate) do very little to check on the practices of these agents. That’s why many of them can get away with charging $5,000 for a job that pays $160 per month.”

Trafficked at sea

Eight Indian seafarers interviewed by Context said they had been trafficked to Iran after being deceived about where they would work and their salaries. All had been put to work on the shadow fleet or on vessels carrying construction materials.

Labour trafficking, as defined by the ILO, refers to the exploitation of individuals through force, fraud or coercion for the purpose of engaging them in work under conditions that violate their human rights.

Victims may be under threat of physical harm, misled over the nature of the work, have their wages withheld or face the confiscation of passports to restrict their movement.

“If you're working on a vessel that's impacted, that's subject to sanctions or blacklisting, then the owners have got you, and they can do whatever they want with you, because they're already unscrupulous, because they're making money on the black market, and they're unlikely to pay you fairly, and they're unlikely to have safety rules,” said Partridge.

Iran-bound seafarers may be trafficked through the Gulf states where they are forced to work on ships under brutal conditions, according to interviews with seafarers and maritime experts.

The ITF worked on the case of a young Indian seafarer who went to the UAE to join a ship but was then brought to Iran, where he was held in a camp for nine months without pay and little food, Trowsdale said.

“We have a zero-tolerance policy for seafarer mistreatment,” a spokesperson for the UAE government said. “If individuals from the UAE are misled into boarding a vessel that is not what they were promised, we will launch an immediate investigation.”

When port authorities do intervene, it can be the seafarers who face the consequences of the shipowner’s crimes, said Bahri.

“Some of these seafarers get arrested for carrying illegal cargoes. They get imprisoned,” he said.

Thriving business

The vast sums netted by countries exporting sanctioned oil means the shadow fleet is thriving.

Russia's oil revenue from its shadow fleet grew by 5% in 2024, reaching $16.4 billion, analysts have said.

That pales in comparison to Iran, which has generated up to $70 billion annually from the sale of crude oil and petrochemicals, according to the U.S. government.

Covert tankers that bypass sanctions have “enabled Iran to continue obtaining a level of revenue from its oil sector,” said Giorgio Cafiero, chief executive of Gulf State Analytics and an adjunct assistant professor at Georgetown University in Washington.

“The Islamic Republic has proven very resilient from a regime survival standpoint, even in the face of all of this economic pressure from the U.S. and other Western countries,” he said.

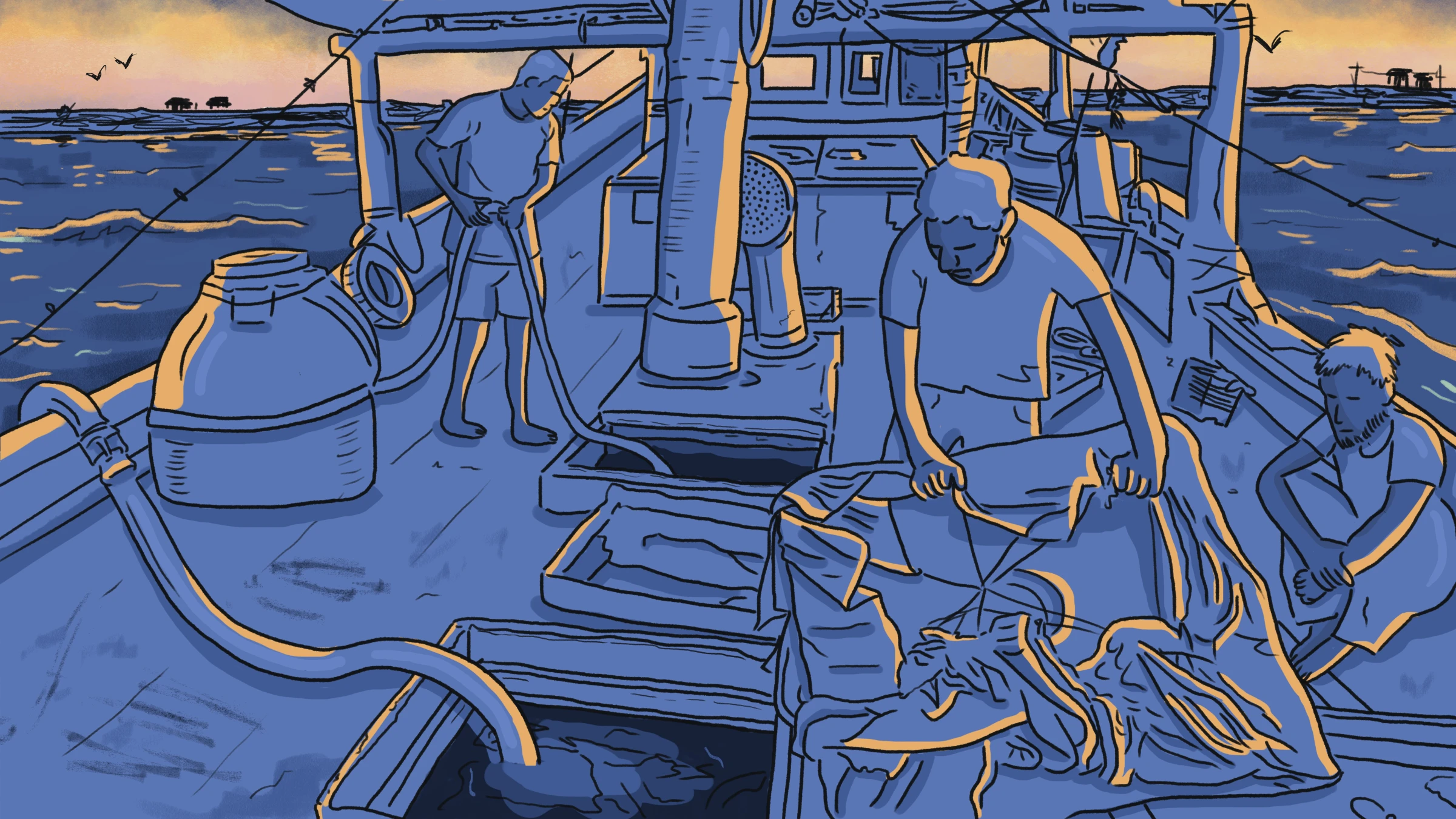

"No salary, always hungry, no rest" : the problems faced by seafarers trafficked to Iran. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

"No salary, always hungry, no rest" : the problems faced by seafarers trafficked to Iran. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

But for the seafarers on board dark vessels, Iran’s sanctions-busting can have deadly consequences.

Two Indian and one Ukrainian crew members were killed when the aging tanker Pablo caught fire off the coast of Malaysia in May 2023.

Ship tracking data showed the Gabon-flagged vessel was in Iranian waters before docking in China. There it delivered Iranian crude four months before the blaze, according to Reuters’ reporting.

Oil from the wreck washed up on Indonesia’s shore, but the cleanup was hampered by the lack of clear ownership and insurance, according to news reports.

“There was no insurance. You’ve got a flag state with a ship full of dead bodies, an explosion and pollution,” said Partridge.

Yet Partridge does not think the risks will deter seafarers looking for work and the stream of recruitment agents targeting them.

“People are desperate for work,” he said. “There is an absolute exploitation opportunity for anybody that wants to do it.”

Singh was stuck on board the Meigou for three months, when the aging boat was forced to return to the Iranian port of Bushehr for repairs.

“When I reached the port, I obtained a SIM card from an Iranian coworker and informed my family and Indian agent Sumit about everything,” Singh said.

Initially, Sumit seemed willing to help, but when Singh’s father phoned him, the agent turned aggressive, telling him “I know people in Iran,” and that he could have Singh killed if he refused to go back to work.

“He also called me, hurling abuses,” Singh said. “My father and I realized Sumit wouldn't help. He was complicit in the exploitation.”

While the boat was being repaired, Singh encountered a group of Indian workers in Bushehr, who shared contact information for ISWAN.

The non-profit worked with local partners in Iran who negotiated with the shipowner, a man Singh only knew by his first name, Hadi, for his release in March 2020.

Both Sumit and Hadi did not respond to WhatsApp messages requesting their responses to Singh’s allegations.

“The experience left me traumatised, and my family suffered alongside me,” said Singh. “My father, particularly, was deeply affected.”

Singh’s father, a veteran of the Indian army, came up with the money to buy him an airline ticket to go home to Uttarakhand in northern India, and Singh arrived on March 22, 2020, the day before India grounded international flights due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Before his departure, Singh requested the wages he was owed for his four months at sea from the shipowner, which totalled $1,000. He was instead offered $20.

But Singh, who has gone on to work on board legitimate large cargo ships, still considers himself fortunate.

“I feel lucky that somehow I managed to escape,” he said. “I am grateful to be free.”

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Ocean Reporting Network.

Reporting: Katie McQue

Editing: Ayla Jean Yackley and Amruta Byatnal

Illustrations: Karif Wat

Production: Amber Milne and Beatrice Tridimas