Uber for nurses? US health workers turn to gig work

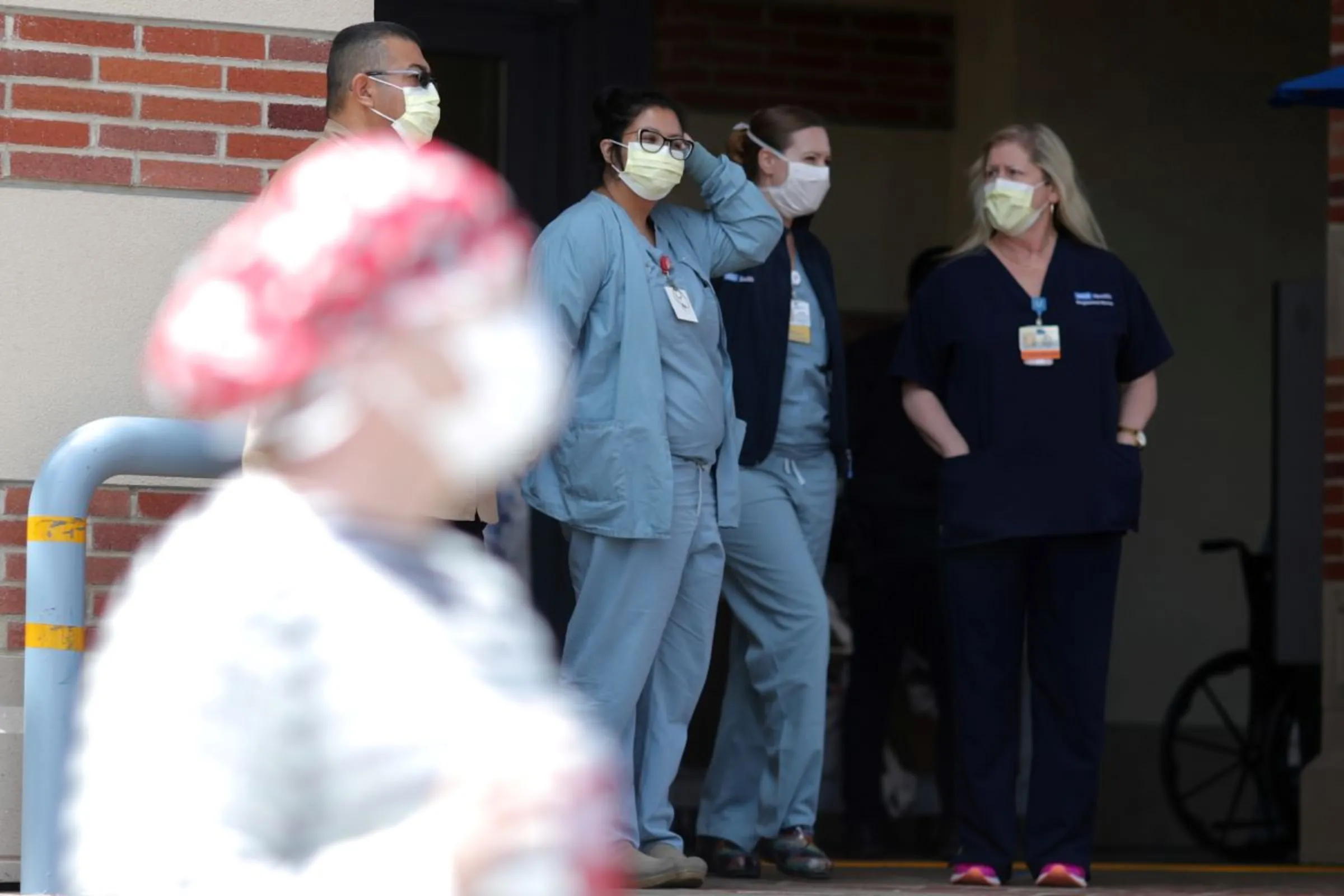

Nurses stand in a hospital doorway watching a nurses’ protest for personal protective equipment at UCLA Medical Center, as the spread of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) continues, in Los Angeles, California, U.S., April 13, 2020. REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson

What’s the context?

Uber-style gig platforms promise U.S. nurses good wages and flexibility - but workers warn against labor abuse and shoddy patient care

- U.S. nurses turn to gig work in care homes

- Uber-style apps promise flexible work, attractive pay

- Reports of rigid, unfair algorithmic app management

Last spring, after six years working as a nurse in care homes around Ohio and making between 500 to 600 dollars a week, Sadie decided she needed to try something new.

On the advice of a colleague, she downloaded Clipboard Health, an Uber-style app that allowed her to book short-term stints in elderly care facilities, for as much as twice the pay of some of the previous jobs she worked.

"I needed more money - I live paycheck to paycheck," - said Sadie, who asked to withhold her real name, in a phone interview.

But she soon found herself penalised by the platform - including having her account frozen - for alleged infractions such as cancelling a shift due to illness, leaving her unable to book new shifts on the app.

Clipboard is part of a growing constellation of gig apps that are trying to bring the Uber-style model of independent contracting to healthcare, as care homes face worsening staff shortages.

"This is one of the many sectors that is being increasingly gig-afied," said Valerio De Stefano, a professor at York University who studies algorithmic management and app-based work.

Although nursing home workers like Sadie are promised flexible jobs, over half a dozen of them working for apps like Clipboard and ShiftKey told Context they felt "controlled" by the platforms' rules and parameters, with little scope to push back.

Nurses reported being told almost nothing about the facilities they were booked in - only to arrive and realise most of the staff were also gig nurses without enough of them to properly care for patients.

A Clipboard spokesperson said in emailed comments that the platform helps healthcare workers "find work that fits their schedule and does not interfere with their other commitments, including personal and family obligations."

The company said that it encourages workers to report any safety incidents, and allows nurses to mark facilities as "Do Not Return" on the app if they no longer want to pick up shifts.

ShiftKey did not respond to a list of questions.

'Gig-afied' sector

Nursing gig platforms are growing in popularity, just as the U.S. experiences an acute labor shortage in nursing homes.

Certified nursing assistants (CNAs) are some of the lowest paid workers in healthcare, where a combination of burnout and low wages have forced staffing levels to a 15 year-low, according to the American Health Care Association (AHCA).

Over 80% of facilities are reporting "moderate to severe" staffing shortages, the AHCA found.

That is pushing nursing homes to rely on more temporary staff, explained Deb Emerson, a consultant with CliftonLarsonAllen who works with nursing home owners.

"Most of our clients are in that position where they would love to be able to hire more staff, but the workforce just isn't there," she said.

"And so they are forced to make a decision either to utilise agency staff or reduce the occupancy in their facility."

The healthcare outsourced labor market - which includes apps like Clipboard - has more than tripled in size over the past four years, growing from $18.8 billion in 2019 to $64.4 billion in 2023, according to Staffing Industry Analysts, a trade publication.

Although there are dozens of contracting agencies for nursing home staff, Clipboard and ShiftKey have expanded rapidly in recent years - both notching valuations over a billion dollars.

Clipboard calls itself a "transformative solution to staffing problems". ShiftKey has said it is "tackling a labor shortage that is crippling the medical system".

Other plaforms, such as CareRev and Papa, have made similar claims for other healthcare jobs such as hospital nursing or in-home health aids.

The new platforms resemble gig economy models such as Uber, where workers are matched with jobs through an app or online platform and then managed through algorithms and rating systems.

For facilities that have a sudden influx of new patients, or staff on leave or off sick, the model offers an enticing option.

"It's easy to just point and click," said Nicholas Castle, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh who studies nursing home staffing.

Nurses are often paid more per hour to work these temporary jobs, he said, in exchange for their willingness to book shifts on-demand.

"I like the flexiblity - to be able to pick which days I work and which days I take off is important to me," said Sadie, a view echoed by other nurses.

One nurse in Brooklyn said that booking shifts through the app was the only way she could make money while juggling childcare and community college classes.

Pitfalls

Though the hourly pay is often higher than full-time work, working for nursing apps also has pitfalls, from account suspensions to tight surveillance, according to six nurses who spoke to Context.

For one of her first shifts booked through Clipboard, Sadie said she was the only nurse working a hall of 20 residents, some of whom had COVID - which she feared might cause her to spread the disease to uninfected residents.

She originally had her attendance score docked - which could lead to the platform freezing her account - when she refused to return to the facility, but later convinced Clipboard to reverse the penalty, according to emails seen by Context.

Months later, her account was frozen for a week when she cancelled a shift because she suffered from a urinary tract infection and could not manage the hour-long drive to the facility she had been booked for.

Clipboard says it freezes accounts for a week when a nurse's attendance score falls below 0 - if three suspensions occur in a six-month period, the account is frozen for an entire year.

New users start with a score of 100, and the app deducts a certain number of points from an account based on how far in advance a nurse cancels a shift they book.

Clipboard directed Context to the app's attendance policy, which says that "canceling shifts will result in points being deducted from your Attendance Score. Points are earned for working shifts, and clocking in on time for shift."

One ShiftKey nurse in Kentucky was banned from the app for a year after his reliability score fell below 85% - he had worked over 450 shifts, and had to cancel around 50 over the course of two years, often due to sickness or family obligations.

ShiftKey says on its website that cancellations within 24 hours of a scheduled shift impact the score.

"The next thing they know their entire work life disappears off the system," said Dane Steffenson, a former Department of Labor (DOL) lawyer who is now in private practice.

"That's really not how it's supposed to work for an independent contractor operating their own business."

Nurses described not being given access to charting software when they arrived at facilities booked through apps - making it difficult to provide continuity of care for patients.

"When you show up in a facility. Clipboard doesn't tell you what patients have trouble walking, who is having seizures - nobody has your back," said one nurse in Brooklyn who had worked for half a dozen facilities around New York.

"Healthcare professionals are not employees of either Clipboard or the facility," said Clipboard, adding that "healthcare facilities are able to fill shifts with qualified healthcare professionals, which enables facilities to provide better care to patients."

In October, investigative news site The Markup published federal inspection reports from a facility in Texas, where investigators suggested that a nurse contracted through ShiftKey may have received insufficient training and contributed to the hospitalisation of a patient.

Like in other sectors of the gig economy such as driving and food delivery, De Stefano says that app-based nursing provides "no real autonomy" for workers.

Algorithms keep tabs on the workers' locations, monitor their performance metrics, and punish behavior that affect the app's bottom line, he said.

One nurse who worked for Clipboard in Ohio said "they use your GPS to know when you are at a facility - and you can only log in once they see you are there. They are watching us."

Clipboard says it tracks nurses' location to be able to predict if they will arrive on time, and to ensure accuracy of when they arrive and depart facilities.

Employees or contractors?

For Castle, certified nursing assistants are put in a precarious situation - where they need that extra dollar an hour but are randomly booked to work at a facility, with potentially damaging outcomes for both patients and nurses.

According to Steffenson, the lawyer, apps that treat nurses like independent contractors are likely illegally misclassifying their workers and should be forced to employ them directly.

They can pay more, and charge facilities less, he said, because they are not paying the taxes and other costs of treating workers as employees.

The Context obtained records of Department of Labor investigations into ShiftKey and Clipboard - neither investigation yielded a penalty.

But Clipboard said it had made changes to "practices and procedures" to underscore the independent contractor status of of its workers - though the details of those changes were redacted from the records.

In 2021 Clipboard paid $2.2 million in a settlement with former workers who said they were not paid overtime nor for breaks, and that they were misclassified as independent contractors, according to legal filings.

The company did not admit wrongdoing - and a similar case against Clipboard is now pending in California.

Labor lawsuits against other gig-nursing apps, including ShiftKey and CareRev, have been filed in multiple states.

Lawyers involved in the suits, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not allowed to discuss settlement deals, said that binding arbitration agreements - which compel workers to settle claims out of court - have frustrated suits.

After her Clipboard account was frozen, Sadie filed her own complaint against the platform with the DOL, which she said is still pending.

Clipboard did not answer questions about what steps workers can take to query unfair disciplinary action - but the Clipboard website does have a form where workers can file dispute claims.

In the meantime Sadie has started picking up shifts on ShiftKey.

"For, now I am just picking up as many shifts as I can with ShiftKey," she said. "I have to make rent."

(Reporting by Avi Asher-Schapiro, editing by Zoe Tabary.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Gig work

- Workers' rights

- Data rights