A revolution in Bangladesh - but what next?

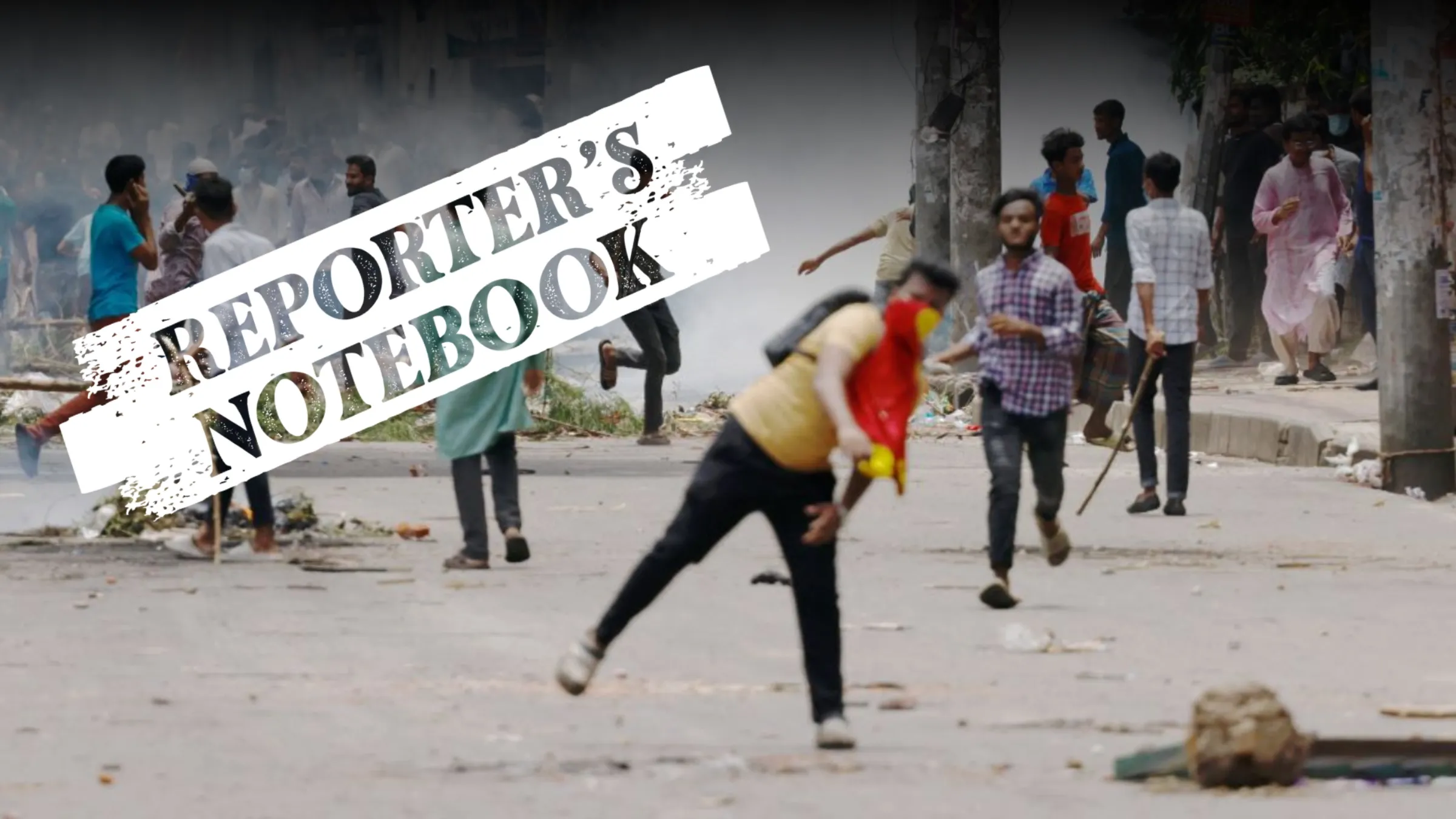

Demonstrators shout slogans after they have occupied a street during a protest demanding the stepping down of Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, following quota reform protests by students, in Dhaka, Bangladesh, August 4, 2024. REUTERS/Mohammad Ponir Hossain

As Prime Minister of fifteen years Sheikh Hasina resigns, how will Bangladesh move forward from bloody protests?

Naomi Hossain is Global Research Professor of Development Studies at SOAS University of London, and the author of ‘The Aid Lab: Understand Bangladesh’s Unexpected Development Success’ (Oxford University Press, 2017).

A long July of bloodshed and violence, initiated by ruling party came to a head on Monday, August 5th. The Prime Minister of fifteen years, Sheikh Hasina, leader of the Awami League, resigned and fled the country by helicopter for India. The final push ultimately came from the scale of the student-led mass movement that had arrayed itself against her rule, and the fact that the army were unwilling to kill any more citizens.

Those citizens, after fifteen years of having their voice silenced with ever more draconian measures, were shocked and angered by her government’s aggressive and heavy-handed handling of what should have been an innocuous student protest against quotas in civil service employment that favoured ruling party followers.

At least 300 people were killed in a month of protests that escalated from a demand to reform the quota system to demands for accountability and justice, and finally to the resignation of the government.

It was an ignoble end to a remarkable political career. Sheikh Hasina is the daughter of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who led the nationalist struggle for independence against Pakistan in 1971.

Feted as a national hero in 1971, he and almost all of Hasina’s family were brutally killed in 1975, after he had turned the democratic Awami League into the single-party BAKSAL while battling an economic crisis, famine, and post-war violence. Sheikh Hasina came to office with a landslide electoral victory in 2009, but then held onto power with a tightening grip over the following 15 years.

Under Hasina, Bangladesh grew at an impressive average rate of 6% per year, despite the pandemic. The economy and the country have changed dramatically. GDP per capita, while still modest, is now higher than in either its erstwhile ruler Pakistan or in India.

In the next few years, Bangladesh is expected to graduate out of the Least Developed Country group of countries, by far the largest country to make this important transition. The Awami League government put in place public services and infrastructure and some governmental reforms that will help Bangladesh in its future development. The emphasis on demonstrating development performance was vital to a government whose power was decreasingly dependent on the legitimacy of fairly won elections, and increasingly on delivering growth.

Yet Bangladesh’s bloody July has demonstrated with crystal clarity the crucial role of accountability and justice – in the development process. You can have all the growth you want, but if it is not fairly distributed, you are dropping seeds into cracks that will soon grow into trees.

It was significant that Sheikh Hasina cried for the brand new metro station that had been destroyed, but not for the hundreds of protestors that were killed: she had bet that modern infrastructure would persuade Bangladeshis that they were living the good life, that their country was no longer the basket case of the 1970s.

As a young generation of Bangladeshis reared on messages of the country’s development progress came of age, they aspired to more than their parents had been content with. This included not just good jobs, secure and satisfying to their sense of wanting to serve their growing country, but also the right to challenge power, particularly when they had never themselves had a chance to choose their rulers.

In the past 15 years, Sheikh Hasina’s rule became increasingly authoritarian. After free and fair elections in 2009, subsequent polls were rigged and the opposition parties jailed or pushed out. The media faced self-censorship, criminalization, or co-optation.

Human rights defenders and civil society organizations, even Professor Yunus, the Nobel Peace Prize-winning founder of the Grameen Bank, had been slapped with targeted, politicized legal charges intended to silence critics and dissenters.

The benefits of economic growth were increasingly skewed towards a small group of very powerful big business houses, party followers, and state officials. The powerful military, police, big business, party militia and other core beneficiaries of the political settlement were deeply invested in the survival of the Sheikh Hasina government.

This is why among the calls for political reform are calls for more technocratic but crucial reforms at the heart of the political economy of Bangladesh, in particular of the banking sector, which had distributed massive loans to the powerful among the party faithful. The task here is not merely clean new elections: it is about re-engineering the institutions of governance so that they are never again so thoroughly captured by those with political power and muscle.

As per the student leaders' demands, Professor Yunus is now chief adviser of the caretaker government. His role will be to lead the transition while the country figures out what to do next.

Bangladesh has been here before: a military-installed non-party caretaker government ruled in 2006-2008, making a valiant effort to clean up Bangladeshi politics after a similar mass movement and political violence pushed out the then-BNP government, which had similarly been accused of repression and corruption.

Now the task for Bangladesh is to learn from the mistakes that allowed Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League to dominate for 15 years, and to rebuild a country reeling from a horrifically bloody July.

Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Context or the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Tags

- Unemployment

- Pay gaps

- Wealth inequality

- Poverty

Go Deeper

Related

Latest on Context

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6