In extreme heat, U.S. looks at worker protection standards

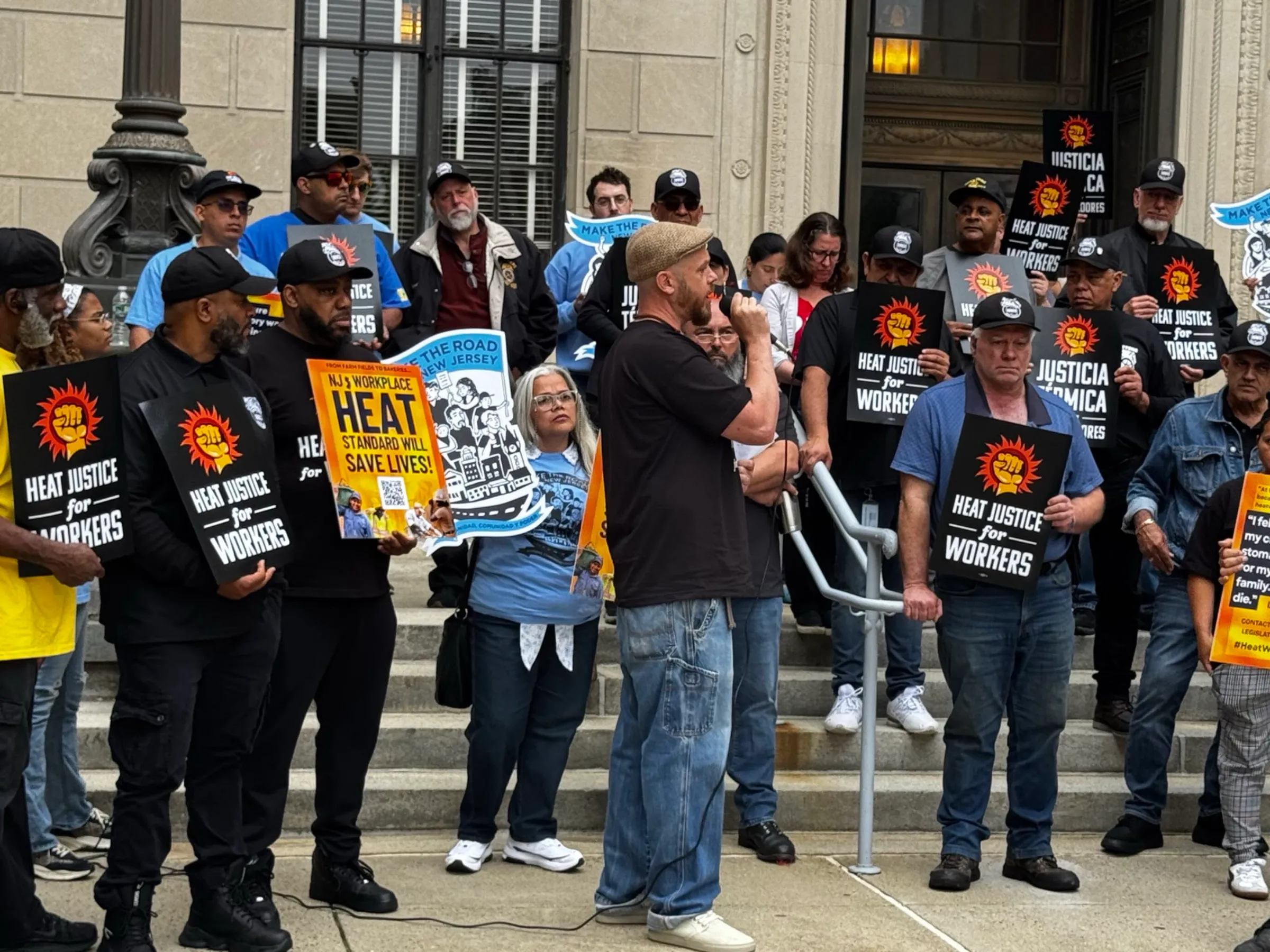

Workers and advocates take part in a Washington event on June 19 in favor of a national workplace heat standard. Fired Up For Heat Justice | National COSH/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

What’s the context?

Amid blazing heat in the United States, worker safety agency OSHA begins first hearings on workplace heat standards.

- Worker safety agency holds hearings for first national standard

- 69 million people at risk in extreme heat in U.S.

- States, cities seek to fill gaps in federal rules

WASHINGTON - Fear for her father's health led Jazmin Moreno-Dominguez to Washington this month to push for a first-ever heat standard for U.S. workers.

Her father suffered a heat-induced stroke a decade ago, but he still needs his construction job in blistering Phoenix, Arizona temperatures, she said at the start of three weeks of public hearings.

“Every day he leaves for work is a day we wait in hopes we don’t hear the same phone call – despair, anxiety, worried that he won’t pass out on the job again,” Moreno-Dominguez, 24, told Context.

She was scheduled to testify at hearings being held by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) through early July, staged just as extreme heat has gripped large parts of the United States.

Moreno-Dominguez's father, an immigrant from Mexico, is 65 and has been working construction for 30 years, with no mandatory rest breaks, water breaks or shade requirements, she said.

Now, for the first time, a national workplace heat standard is under consideration in a bid to protect workers' health and reduce rising heat-related illness costing $1 billion a year in hospitalizations.

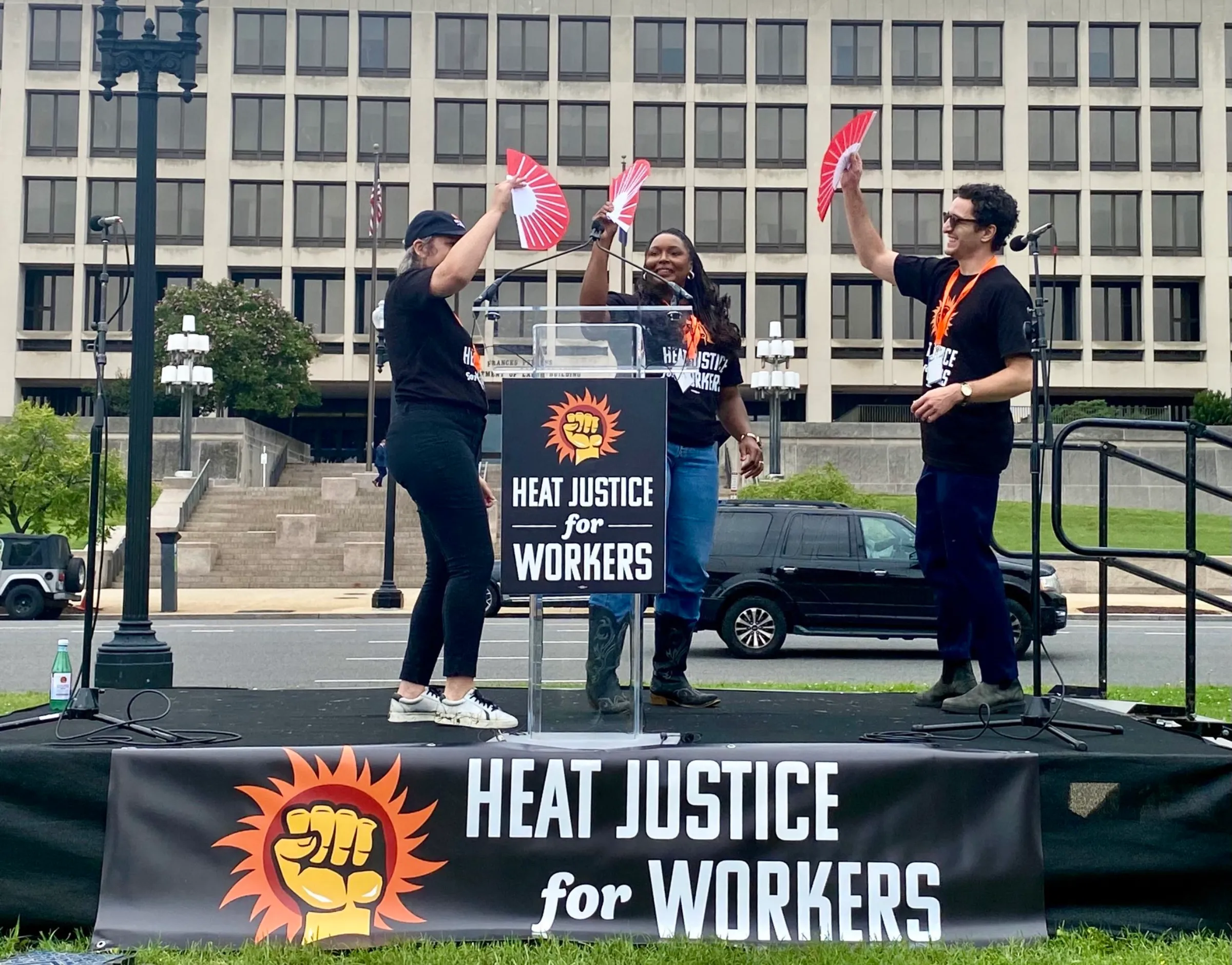

Workers and advocates take part in a Washington event on June 23 in favor of a national workplace heat standard. Fired Up For Heat Justice | National COSH/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Workers and advocates take part in a Washington event on June 23 in favor of a national workplace heat standard. Fired Up For Heat Justice | National COSH/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

At-risk workers

More than 69 million U.S. workers are at risk from extreme heat as summer begins, according to the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health (COSH), a network of worker safety organizations that launched its heat campaign last year.

Brittney Jenkins, a COSH coordinator, has been helping workers prepare their testimony.

"You're in the fields, in the restaurants and warehouses," she said. "You don't need a fancy title to say what it's like to work in a workplace in 103 degrees."

Extreme heat poses multiple health risks, including cardiovascular and kidney disease, and increases the prospect of workplace injuries.

President Donald Trump's administration has slashed funding for the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the agency whose research undergirded the proposal, while top heat experts have been fired or laid off.

A Department of Labor spokesperson said in an email that once the hearings end, the agency will “take everything into consideration and make a decision on how to proceed.”

Rising global temperatures

OSHA, which oversees workplace safety, requires employers provide a safe workplace but has no specific standards for heat.

Meanwhile, heat is on the rise. Globally, 2023 was the warmest year on record, with almost 120,000 heat-related emergency room visits in the United States.

That year also saw record heat-related deaths, which have increased by 119% since 1999, according to the American Medical Association.

Efforts to quantify the impacts of workplace heat problems are plagued by patchy data and assumed underreporting, said Jill Rosenthal, director of public health policy at the Center for American Progress, a Washington think tank.

Heat-induced declines in labour productivity account for $100 billion every year in the U.S., according to research cited by the Center, and those losses are projected to reach $500 billion by 2050.

The proposed standard is strong, Rosenthal said, requiring employers have heat illness prevention plans, identify potential heat risks, prepare emergency responses and allow employees to acclimate to high temperatures.

Industry groups have objected, with the National Association of Home Builders calling the rest breaks and acclimatization mandates “overly prescriptive” and warning it could affect housing affordability.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce urged OSHA to withdraw the proposal in favour of one in which employers could “tailor their protections to their geography, environment, workplaces, and workers."

Amid uncertainty over federal action, Rosenthal said cities and states are stepping in with their own protective standards, with at least seven states doing so in the past three years.

But states such as Texas and Florida have barred local governments from passing their own heat standards.

In Texas in 2010, a few cities adopted heat protections, but those were halted by the state in 2023, said David Chincanchan, policy director with the Workers Defense Action Fund.

“The state government went from not taking action to outright obstructing heat safety protections,” he said.

The issue is particularly difficult for immigrant workers, many of whom fear retaliation if they complain, he said.

Veronica Carrasco, a mother of three who immigrated to the United States in 2010 and works in construction in Dallas, said she has felt weak and nauseous in the heat and takes rest breaks even if not allowed.

"I've never had a positive answer from bosses when I’ve asked for something to be able to work in the heat. They don’t have a reason to provide any of these things because it’s not mandated by law,” Carrasco, 41, said through a translator.

"The can get away with it because this is a very vulnerable community. People in construction need the work and don’t have a lot of options."

(Reporting by Carey L. Biron. Editing by Anastasia Moloney and Ellen Wulfhorst)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Extreme weather

- Workers' rights