Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

People walk past a COP29 logo during the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29), in Baku, Azerbaijan November 14, 2024. REUTERS/Murad Sezer

Trump is the ghost at the COP29 feast as delegates at Baku climate talks assess the impact of his stunning comeback

BAKU - He's not in the room but he's the talk of the town.

As delegates scuttle round COP29 climate talks in Baku, President-elect Donald Trump is the name on everyone's lips.

For this climate reporter, covering COP is about as good as work gets, chasing after climate wonks, world leaders and delegates from nearly 200 countries as they rush between panels and speeches in Azerbaijan's state-of-the-art Olympic stadium.

The stunning political comeback staged by Trump - who calls climate change a hoax - has cast a shadow over the summit's opening days.

But what's less clear is how Trump and his commanding Republican victory will affect COP29 negotiations, as the world faces up to the task of agreeing finance for developing nations.

Who better to ask than Ali Zaidi, National Climate Advisor to outgoing President Joe Biden.

I put it to Zaidi that fears were circulating at COP that a new man in the White House could dramatically shift the U.S. diplomatic position, making financing global climate change action even harder.

"I don't think there's one country that is an essential one in sustaining the dialogue or sustaining the progress," Zaidi told me at the jam-packed stadium.

He pointed out that the New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance (NCQG) - that's the catchy name for the elusive financial target under negotiation - is looking out to 2035, whereas administrations come and go every four years.

But despite his brave face and avowed long-term outlook, a lot will change with Trump back in power.

The incoming head of the world's No. 1 economy and No. 2 emitter is expected to retreat significantly from global climate efforts when he takes over in January.

Trump has already said that he plans to leave the Paris climate agreement at the earliest opportunity, and his staffers have even floated leaving the UNFCCC, the United Nations convention that launched the whole COP process.

"I don't mean to sugarcoat the result of the election or the consequences of a dramatically changed prioritisation from policy leaders in Washington," Zaidi told reporters.

"Those are meaningful leadership matters and there's no talking around that."

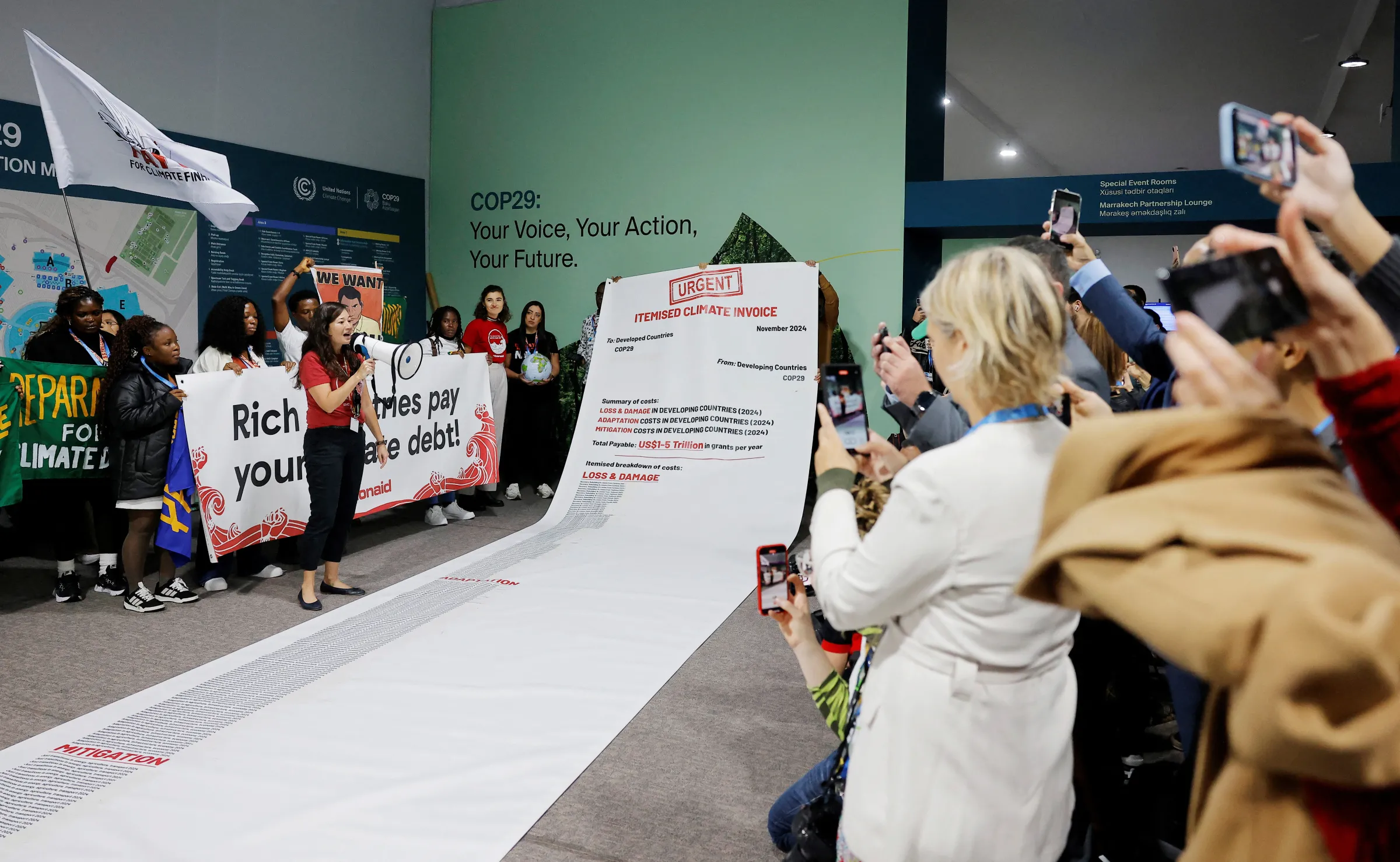

Activists display a 10 metre long climate invoice directed at developed countries at a protest during the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29), in Baku, Azerbaijan November 14, 2024. REUTERS/Maxim Shemetov

Activists display a 10 metre long climate invoice directed at developed countries at a protest during the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29), in Baku, Azerbaijan November 14, 2024. REUTERS/Maxim Shemetov

He's not alone in that view.

Reports of widespread malaise over Trump's election are indeed somewhat overdone.

Countries still have an awful lot of bread-and-butter business to attend to here, and global talks about securing the future are continuing at a rate, whoever won the election.

"I don't think the rest of the world is going to let Donald Trump hold us hostage," said Mohamed Adow, director of non-profit Power Shift Africa.

"If we relied on the White House to save the planet, we really would be in trouble. We've not even been doing that with a Democrat in charge," he told me.

In fact, many delegates drily note that Washington has not been much of a contributor to international climate finance deals given its share of emissions, eclipsed only by China.

It tends to fund global climate efforts other ways such as through the World Bank - as its biggest shareholder - or the U.S. Agency for International Development.

What did Trump's near-neighbour think?

I sat down with Catherine McKenna, Canada's environment minister during Trump's first term as president in 2017-2021, to get her views.

She said it has always been "tricky" to wring financial commitments out of the United States and noted that things had changed a lot since 2017 when the "clean energy revolution" was not yet underway.

As Trump threatens a retreat from multilateral commitments, it remains to be seen whether the world will win the kind of funding that developing nations and U.N. agencies say is needed.

It's not loose change we're talking about here - but trillions of dollars.

Judging by the poor turnout from heads of state - leaders of the world's top 13 polluters all went AWOL and opted to skip the Baku talks - finding big pots of money could be an uphill task.

As many countries stall, McKenna is looking to new sources of funding as the chair of a U.N. group encouraging action from non-state players, such as businesses and cities.

Trump redux aside, McKenna said the damages wreaked by floods, fires and other climate-driven weather extremes make a transition inevitable - whether it's orderly or not.

"It will be harder. It will likely be slower. But no one country can stop progress on this," she said.

(Reporting by Jack Graham; Editing by Lyndsay Griffiths.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles