Intersex Russians fear fallout from curbs on gender-affirming care

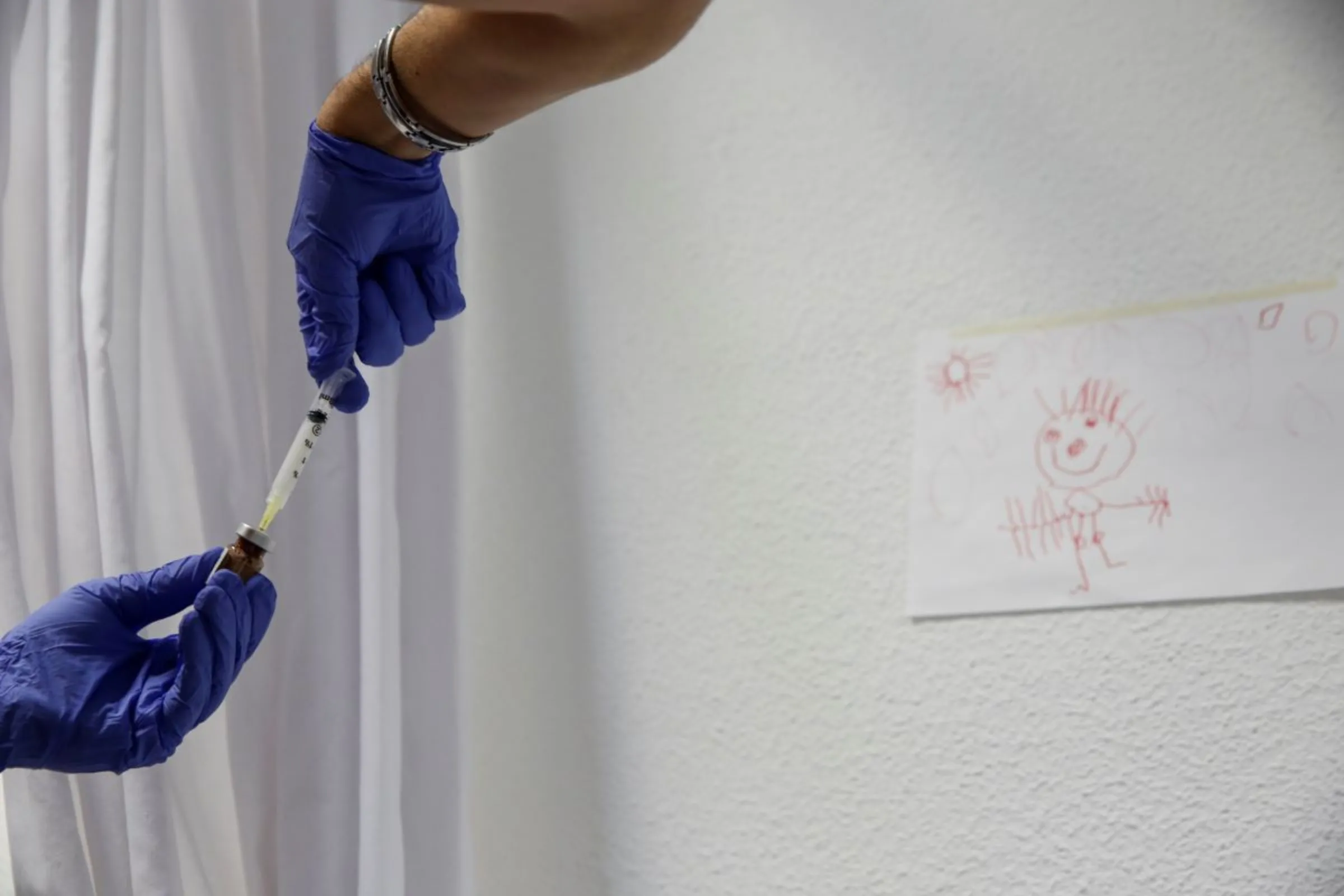

A nurse prepares a hormone blocker for a transgender teenager, at a health-care centre in Madrid, Spain, December 16, 2015. REUTERS/Susana Vera

What’s the context?

Fearing prosecution under a new law, Russian doctors are wary about treating intersex patients - even though they are exempt

- Russia banned transgender healthcare earlier this year

- Intersex people say new law disrupts their treatment

- Activists warn about conflating LGBTQ+ and intersex issues

LONDON - Born intersex and raised as a boy, Polina has known for years that she wanted to live as a woman.

But Russia’s sweeping curbs on gender-affirming healthcare have made that much more difficult.

The 33-year-old from Moscow said that since a new law - which targets transgender people - was passed in July, doctors had been wary about prescribing her female sex hormones and other gender-affirming treatment for fear they could lose their licences or face prosecution.

"The law likens any treatment, even if justified and vitally necessary, to wrongdoing," Polina told Openly in a message chat, asking for her surname to be withheld for privacy reasons.

Intersex people are born with atypical chromosomes or sex characteristics, meaning they cannot be easily categorised as either male or female.

Many undergo surgery as infants to bring the appearance and function of their genitalia into line with that expected of males or females, a practice that has been banned in many European countries but remains legal in Russia.

The new law, which bans legally or medically changing gender, does allow people described as having "congenital anomalies" to undergo medical interventions and then change legal gender, but intersex rights advocates say it is vaguely worded and poorly understood by doctors.

"The bill doesn't list the intersex variations that would allow for a person's documents to be changed," said Ilia Savelev, a co-director and legal adviser at ARSI, a group that supports intersex people in Russian-speaking countries.

Despite the new legislation, Polina was able to change her legal gender on her identity documents to female in late October, but campaigners said they feared other intersex people could be wrongly denied that right.

"Many may not be able to change their documents if their sex variation is not deemed appropriate grounds for it," said Alin, another co-director of ARSI and founder of nfp.plus, a website publishing information about intersex issues.

The Russian Health Ministry did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

Intersex surgeries

Intersex rights advocates are also concerned that the legislation explicitly sanctions medical interventions to "correct" the sex of intersex people.

"Previously, there was simply no ban on such practices; now, there's explicit permission," Savelev said, adding that the law has "sent Russia back years" on intersex rights and put it at odds with a European shift to ban "sex-normalising" surgeries.

In 2015, Malta became the first country to ban medically unnecessary surgeries carried out on intersex children without their consent. Other European Union countries have followed suit or tabled proposals for similar bans.

Eva-Lilit Tsvetkova, a Russian endocrinologist who specialises in caring for trans and intersex patients, called instead for a policy of "normalising" intersex bodies.

Tsvetkova said that while there was occasional need for "corrective" surgeries on intersex babies – for example, where their anatomy made urination difficult – many are medically unnecessary and can lead to long-term complications, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and incontinence.

"A large subset of these operations are 'cosmetic'," she said. "There's never been a medical body of evidence for why they're needed, just a hypothesis by doctors that if a child's genitals look 'non-standard', this may impact their well-being."

Others said they were concerned that intersex people had been mentioned in the legislation at all, saying the law's distinction between them and trans people appeared a crude attempt to justify anti-trans measures.

"Intersex people's needs (for gender-affirming treatment) are presented as having a biological basis, while those of transgender people are seen as simply whims," Savelev said.

Rights under threat

The gender change law was the latest step in a widespread crackdown on LGBTQ+ rights, which President Vladimir Putin seeks to portray as evidence of moral decay in Western countries.

Last year, he signed a law expanding Russia's restrictions on the promotion of what it calls "LGBT propaganda" and in June, the Health Ministry said Russian clinics would soon be staffed with sexologists to help patients "overcome" homosexuality and various sexual "mental disorders".

Besides their concern about the impact of the gender law passed in July, the crackdown on LGBTQ+ rights has unsettled intersex rights campaigners in Russia.

Anton, an intersex activist based in Moscow who asked not to use his full name, voiced concern that Western rights groups often conflate LGBTQ+ and intersex issues in their advocacy.

He said intersex and LGBTQ+ campaigning should be kept separate to protect children from an increased risk of unnecessary "corrective" surgeries in socially conservative countries.

"If, in Russia or a conservative Muslim region, the parents of an intersex child see information saying their child is LGBT, it could do them a world of harm," he said.

(Reporting by Joanna Kozlowska in London; Editing by Helen Popper and Hugo Greenhalgh.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Inclusive Economies

- LGBTQ+