Ahead of COP30, environmentalists risk freedom to defend nature

A woman holds a sign during a protest against the disappearance of Mapuche leader Julia Chunil, in front of La Moneda presidential palace in Santiago, Chile January 8, 2025. REUTERS/Juan Gonzalez

COP30 in Brazil is an opportunity to spotlight the risks facing environmentalists and to ramp up measures to better protect them.

Ana María Palacios Briceño leads civic space research for the Americas at the CIVICUS Monitor. Eduardo Marenco leads the advocacy and campaign work in the Americas for CIVICUS.

Kenia Ines Hernández is an Indigenous woman, feminist and human rights lawyer from Guerrero, Mexico. She grew up speaking the language of her Amuzgo community, and for years defended the rights of her people.

But that commitment has come at a steep cost. Hernández is currently serving two prison sentences totalling nearly 22 years for her environmental human rights activism.

Mexican authorities arrested her in 2020 and convicted her for "aggravated battery," in a trial that the American Bar Association has said was "riddled with irregularities."

Earlier this year, a judge dismissed some criminal charges against her, but Hernández remains locked up.

Today on Nelson Mandela International Day, we recognise Hernández’ struggle, and demand her freedom as part of the Stand As My Witness campaign, which calls for the release of incarcerated human rights defenders around the world.

Unfortunately, Hernández’ case is far from unique. Instead, her persecution is emblematic of the growing abuse of legal systems by governments across the Americas seeking to delegitimise people defending collective rights and dismantling community resistance.

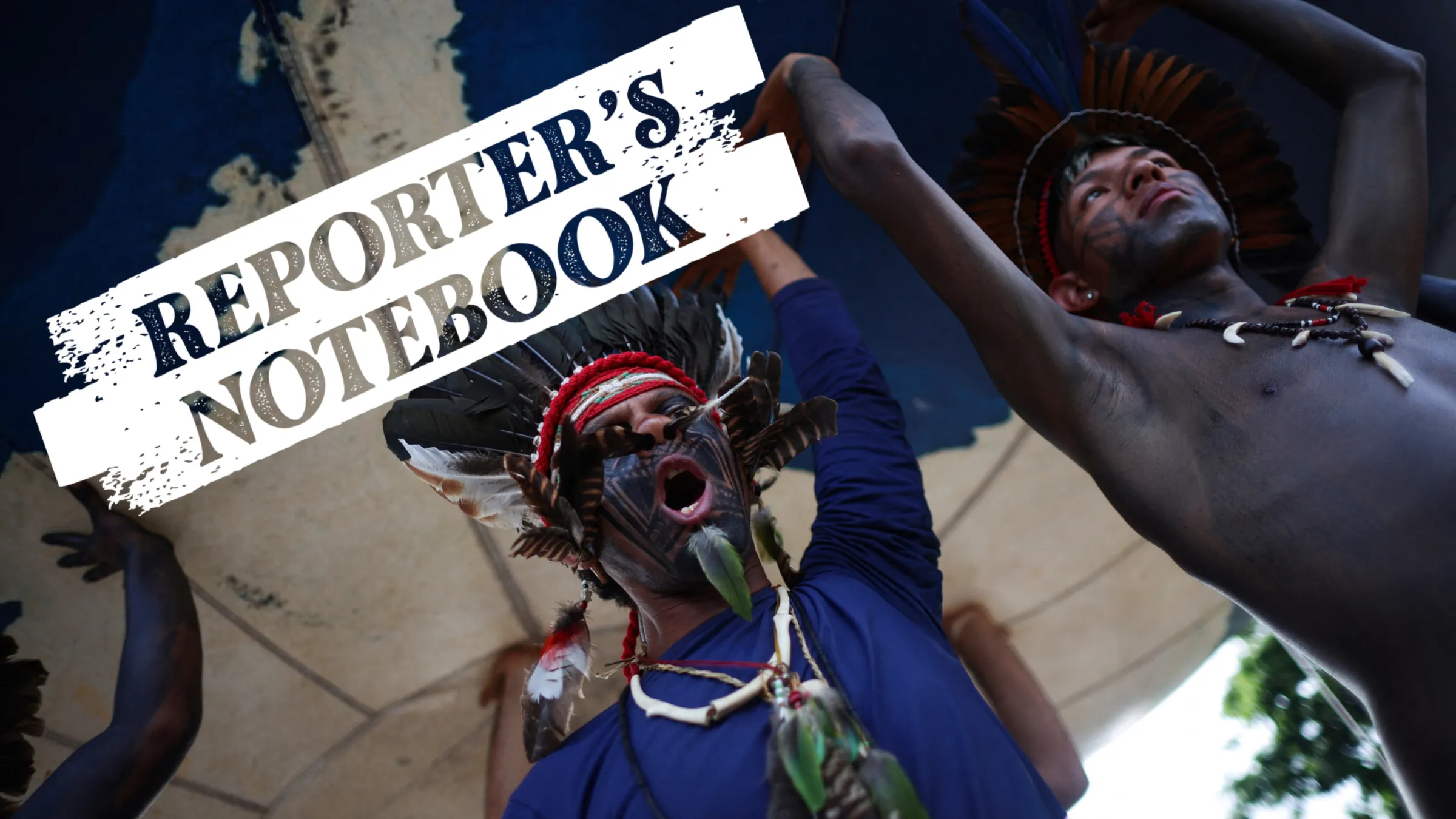

From the Wet’suwet’en Nation in Canada to Mapuche communities in Chile, environmental and land defenders are being targeted for protecting their territories and ancestral cultures, and for defending the climate, land and water we all depend on.

In Mexico alone, environmental defenders are increasingly criminalised, with at least 77 incidents recorded in 2024 by the Mexican Center for Environmental Law (CEMDA), most involving rural and Indigenous activists.

These crackdowns not only silence those who speak out. But they try to break grassroots movements and criminalise solidarity when the climate emergency and the rush for an energy transition make environmental activism more crucial than ever.

But criminalisation is only the beginning.

CIVICUS Monitor research shows environmental and land defenders across the Americas face systematic stigmatisation, threats, and even targeted killings, often by armed groups linked to corporate or state interests.

Indeed, the Americas is the world's deadliest for people protecting land and the environment, with most fatal attacks occurring in Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico and Peru.

Still, there have been positive developments which could reverse this trend.

The 2018 Escazú Agreement, which entered into force in 2021, is the first legally binding treaty in Latin America and the Caribbean aimed specifically at protecting environmental human rights defenders.

Unfortunately, implementation has been painfully slow. Only 24 countries have signed it, and just 18, including Mexico, have ratified it, representing around 44% of the region's population.

More countries must urgently join, finance and implement the Escazú Agreement, but momentum for environmental justice is building elsewhere too.

Just weeks ago, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued a landmark advisory opinion affirming that states and corporations have binding human rights obligations to prevent, reduce and remedy harms caused by the climate emergency. The opinion also reinforced protections for environmental defenders.

Further, this year's COP30 climate summit will be held for the first time in the Amazon, in the city of Belém, Brazil.

It creates an incredible opportunity to focus attention and action on protecting environmental defenders in the Americas.

The symbolism of holding COP30 in the heart of the world's largest rainforest is undeniable. The Amazon plays a crucial role in regulating the global climate. But those who defend it, particularly Indigenous communities, face violence for resisting illegal mining, deforestation and other threats.

In this urgent context, COP30 organisers must step up and ensure that frontline voices are heard when climate decisions are made in Belém.

This includes championing the Leaders Network for Environmental Activists and Defenders(LEAD)initiative, which seeks high level commitments for protection of environmental human rights defenders and their communities.

But frontline voices cannot be heard if they are behind bars or dead, so governments in the Americas must start respecting environmental defenders now.

Mexico can lead the way by releasing Kenia Ines Hernández.

Freeing her would send a powerful message across the region and the world that defending environmental and land rights is not a crime. Instead, it is essential, and deserves protection, not punishment.

Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Context or the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Tags

- Indigenous communities

Go Deeper

Related

Latest on Context

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6