Reporter's notebook: Camped out with Brazil's protesting Indigenous

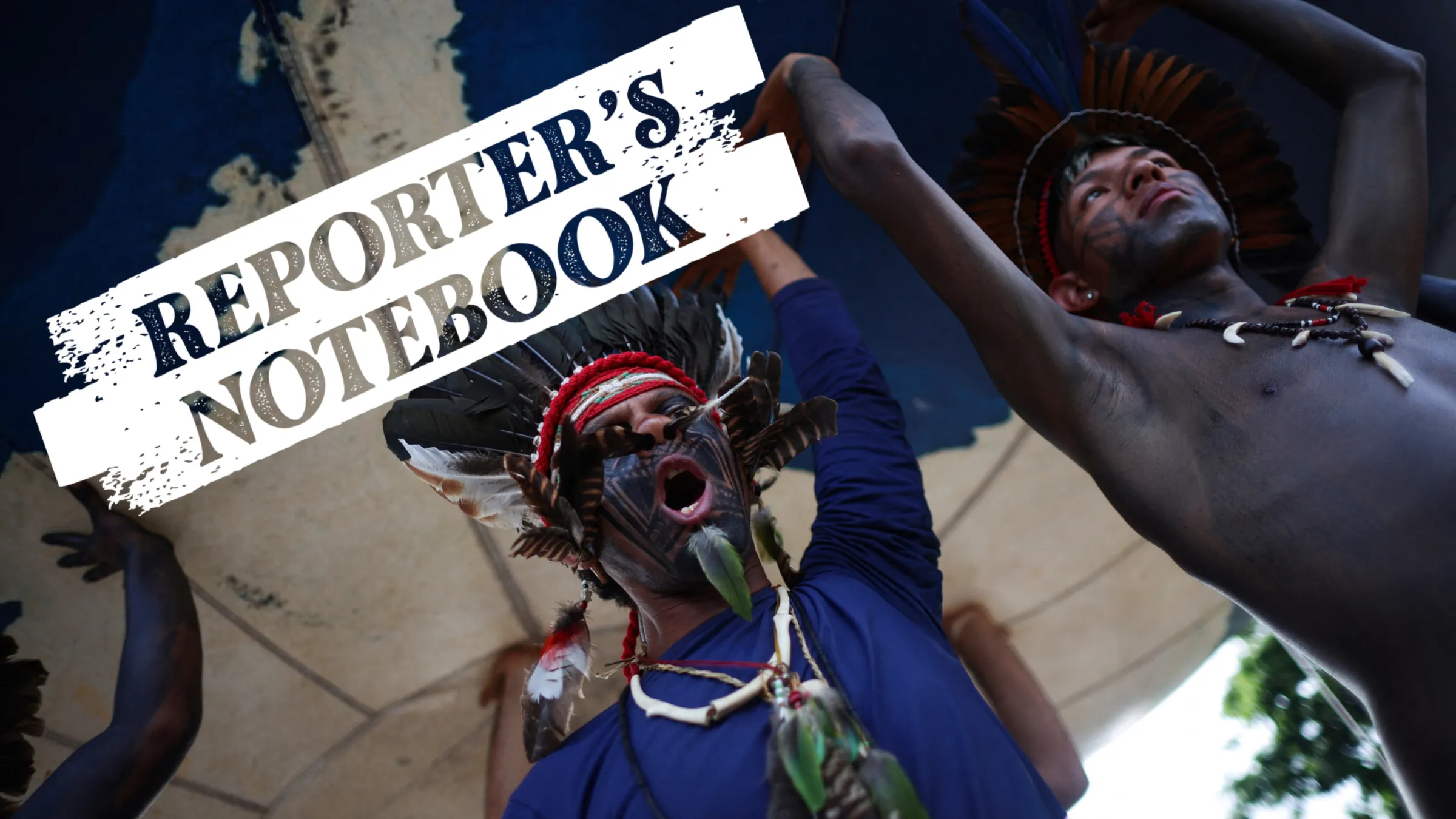

Indigenous people take part in the Terra Livre (Free Land) protest camp to demand the demarcation of land and to defend cultural rights, in Brasilia, Brazil April 10, 2025. REUTERS/Adriano Machado

What’s the context?

In their largest annual gathering in Brasilia, the Indigenous face police gas to march on Congress for their rights.

BRASILIA - Under a blue April sky in Brasilia, the skyline is cut by sculptural, air-conditioned modernist buildings. The structures are surrounded by parking lots and curving, broad avenues with concrete sidewalks.

Brasilia was purposely built here, a modernist push by governments in the 1950s and 1960s largely to help occupy the country's vast interior.

But the capital's construction also meant the bulldozing of vast areas of the Cerrado tropical savannah and rainforests as roadways were built to connect it to the Amazon and other areas at the expense of Indigenous communities.

For a few days in April every year, the city lends itself to the Free Land Camp, Brazil's largest Indigenous gathering, and it becomes a centre of protest.

Brasilia's central location makes it easier for Indigenous groups from opposite corners of Brazil to gather, demand land rights and meet with authorities.

As I follow the Indigenous march towards Brazil's Congress, I hear songs in dozens of languages, paced by maracás and foot stomping. Participants wear body paint and feathers.

From a flyover, local residents draw out their phones to take pictures.

Brazil’s Indigenous Congresswoman Celia Xakriaba and Brazil’s Minister of Indigenous Peoples Sonia Guajajara attend the Terra Livre (Free Land) protest camp to demand the demarcation of land and to defend cultural rights, in Brasilia, Brazil April 8, 2025. REUTERS/Ueslei Marcelino

Brazil’s Indigenous Congresswoman Celia Xakriaba and Brazil’s Minister of Indigenous Peoples Sonia Guajajara attend the Terra Livre (Free Land) protest camp to demand the demarcation of land and to defend cultural rights, in Brasilia, Brazil April 8, 2025. REUTERS/Ueslei Marcelino

Organised by the umbrella organization Apib, or the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, this is perhaps Brazil's most important environmental meeting, drawing more than 7,000 people this week, according to organisers.

Over the last decade, there have been a series of attempts in Congress to open up more Indigenous territory for mining and to establish a cutoff date that would make it impossible for Indigenous people to legally recover land they had not settled on by 1988.

Indigenous groups here are demonstrating for one main cause: that their right to reclaim land is upheld, a form of reparation for losses due to the expansion of farms and cities into natural areas they occupied.

This means they also want an end to illegal invasions, primarily by loggers and miners, that are destroying the Amazon rainforest and other ecosystems.

As night falls in Brasilia, the multitude approaches Congress as a police helicopter sheds a beam of light over the ground.

When people come closer to the heart of Brazil's political power, police officers fire smoke bombs to disperse the crowd.

Amid the thick smoke, an Indigenous girl falls to the ground and is helped back up; others are taken away in ambulances, spurring outrage in the Indigenous movement.

Friends text me asking if all is OK as I walk back to the camp along with the retreating crowd.

Everything appears normal when I reach the hundreds of tents that make up this makeshift, Tower of Babel-like community.

Kids run around as a documentary is displayed in a tent by a leading Indigenous organisation.

Nearby an Amazon rainforest community debates with public officials and an NGO about how to take legal action against a bank that has been accused of funding invaders.

A drone view shows the the Terra Livre (Free Land) protest camp as indigenous people camp to demand the demarcation of land and to defend cultural rights, in Brasilia, Brazil April 9, 2025. REUTERS/Adriano Machado

A drone view shows the the Terra Livre (Free Land) protest camp as indigenous people camp to demand the demarcation of land and to defend cultural rights, in Brasilia, Brazil April 9, 2025. REUTERS/Adriano Machado

Indigenous lawyers discuss strategy on how to protect their land rights. New regional youth groups are launched.

Under a tent where Indigenous people had been making body paint during the day, a small assembly takes place in a native language.

On the main stage, a pop music band plays to a dancing crowd, while in a large, tent-like structure, a small rave rages as teenagers stomp their feet and families sit and watch.

A friend from the Indigenous movement told me that the gathering is smaller this year, as organisations are saving up to take more people to the COP30 United Nations climate talks in Belém, in Brazil's Amazon, in November.

There, delegates from all over the world will hear the Indigenous movement's motto that has rung throughout this year's Free Land Camp: "A resposta somos nós" or "We are the answer."

(Reporting by Andre Cabette Fabio; Editing by Ayla Jean Yackley.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Adaptation

- Climate inequality

- Forests

- Indigenous communities