Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

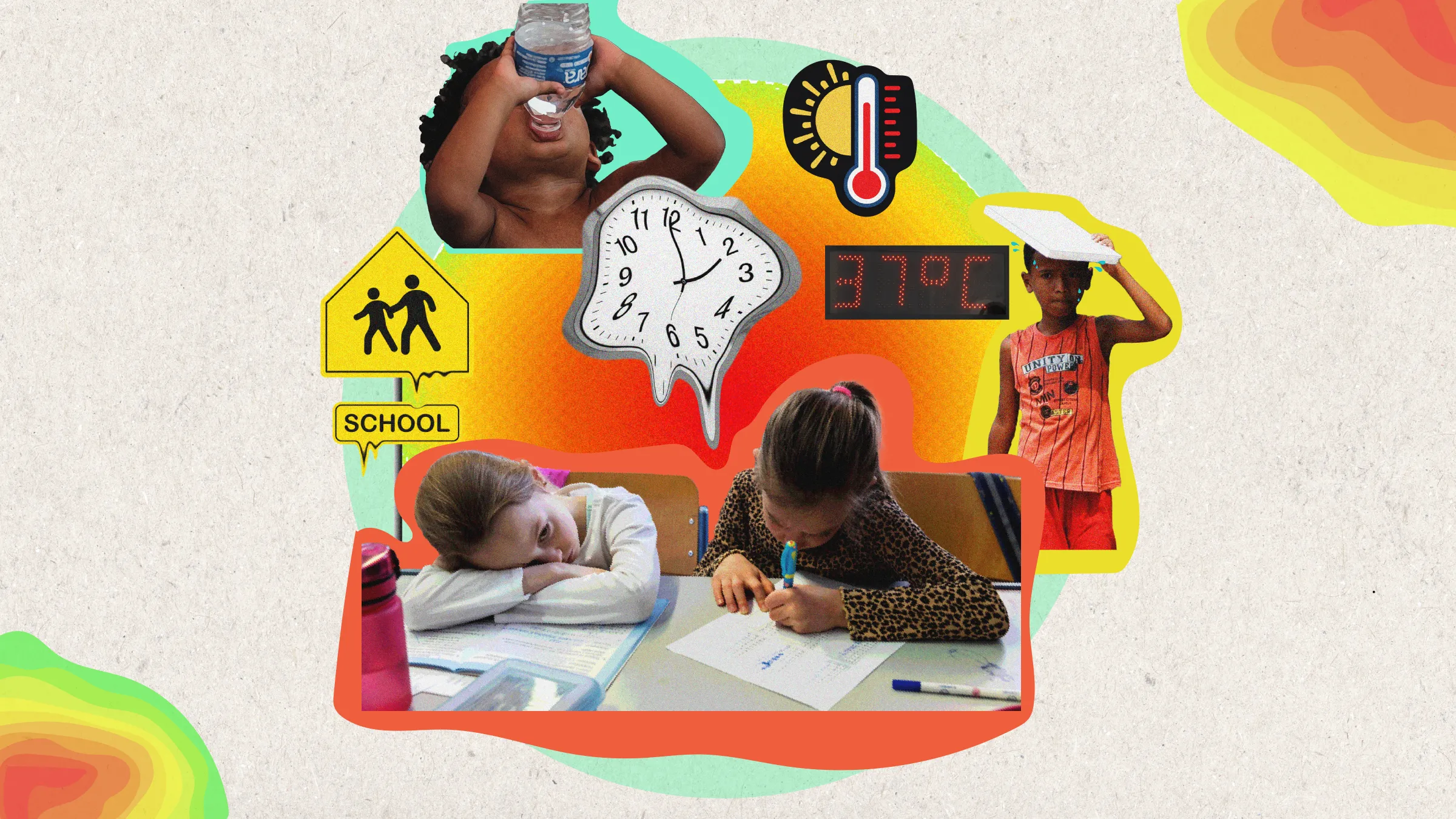

Children study in a classroom in this illustration photo. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Mayo Akin-Oteniya

What happens to a child's body when they sit in class during a heatwave and what does this mean for their long-term health?

LONDON - When a child is too hot for too long, a chain reaction across the body and brain affects everything from immediate concentration to long-term cardiovascular and mental health.

It is a critical risk in a warming world where last year an estimated 171 million students had their schooling disrupted by more intense, longer and more common heatwaves.

Adults cool down by redistributing blood flow to the skin and by sweating. But young children heat up more quickly and sweat less, meaning they stay hotter for longer. They also depend on adults to help them keep cool and stay hydrated.

A working paper published by the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University in 2024 said severe heat can lead to "muscle breakdown, kidney failure, seizure, coma, or even death in extreme cases".

One key factor is the behaviour of heat shock proteins, produced by cells in response to exposure to stressful conditions.

"When temperatures get higher, heat shock proteins are activated and they act like chaperones. They protect other important molecules in our bodies from breaking down," Lindsey Burghardt, chief science officer at the Center on the Developing Child, said in an interview.

"But at really high temperatures, heat shock proteins break down, and the proteins they are supposed to be protecting can't function or are broken down. Then ... the immune system is mis-directed, and it starts thinking of these broken-down proteins as foreign invaders."

The damage from this "cascade of reactions" can affect the brain, immune system, heart and other muscles.

The effect of extreme heat on children's ability to learn has been well documented. But it's not just book-learning that suffers.

"A lot of learning in early childhood happens through play - negotiation with peers outside, solving arguments on their own, working through challenges, climbing high risky things," said Burghardt.

When it is too hot, this process is compromised.

Heat also destabilises the neurotransmitters that help steady our moods.

"If there are threats to well-being - and the brain detects extreme heat as a threat to our well-being – there's activation of the stress response system," Burghardt said.

"If this happens in early childhood it can disrupt the formation of the circuits that form the foundation of our mental health throughout our lifespan, because these circuits are rapidly developing in early childhood."

Burghardt noted that extreme heat disrupts sleep, affecting children's mental and behavioural health and well-being and how well they function the next day.

Sleep deprivation affects children's ability to process emotional experiences, and persistent disruption from heat can have long-lasting consequences.

"This can raise the risk of a range of adverse mental health outcomes across your lifespan, raising your risk of mental health disorders but also physical disorders," Burghardt said.

As global temperatures rise, and climate experts warn of worse to come, schools must adapt to new extremes. But effective cooling is a "powerful and exciting antidote," Burghardt said.

Studies have shown that lowering a classroom temperature from 30 degrees Celsius (86°F) to 20°C (68°F) can improve performance by about 20%.

"We need to be thinking about how are we adapting our infrastructure as things get warm and stay warm. It's not just the learning that's happening in the schools but what's happening when school itself can't happen," Burghardt said.

If classrooms shut suddenly because of extreme heat, children will experience the rest of the day very differently depending on their access to resources or their caregiver situation. Parents may be unable to leave work or face economic implications if they do.

Despite the rising temperatures and extreme weather, Burghardt refuses to countenance a dystopian view of a world where children cannot go outside, because she believes humans can adapt.

"I'm not willing to accept that version of reality. I think we can do better."

(Reporting by Clár Ní Chonghaile and Diana Baptista; Editing by Ayla Jean Yackley.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles