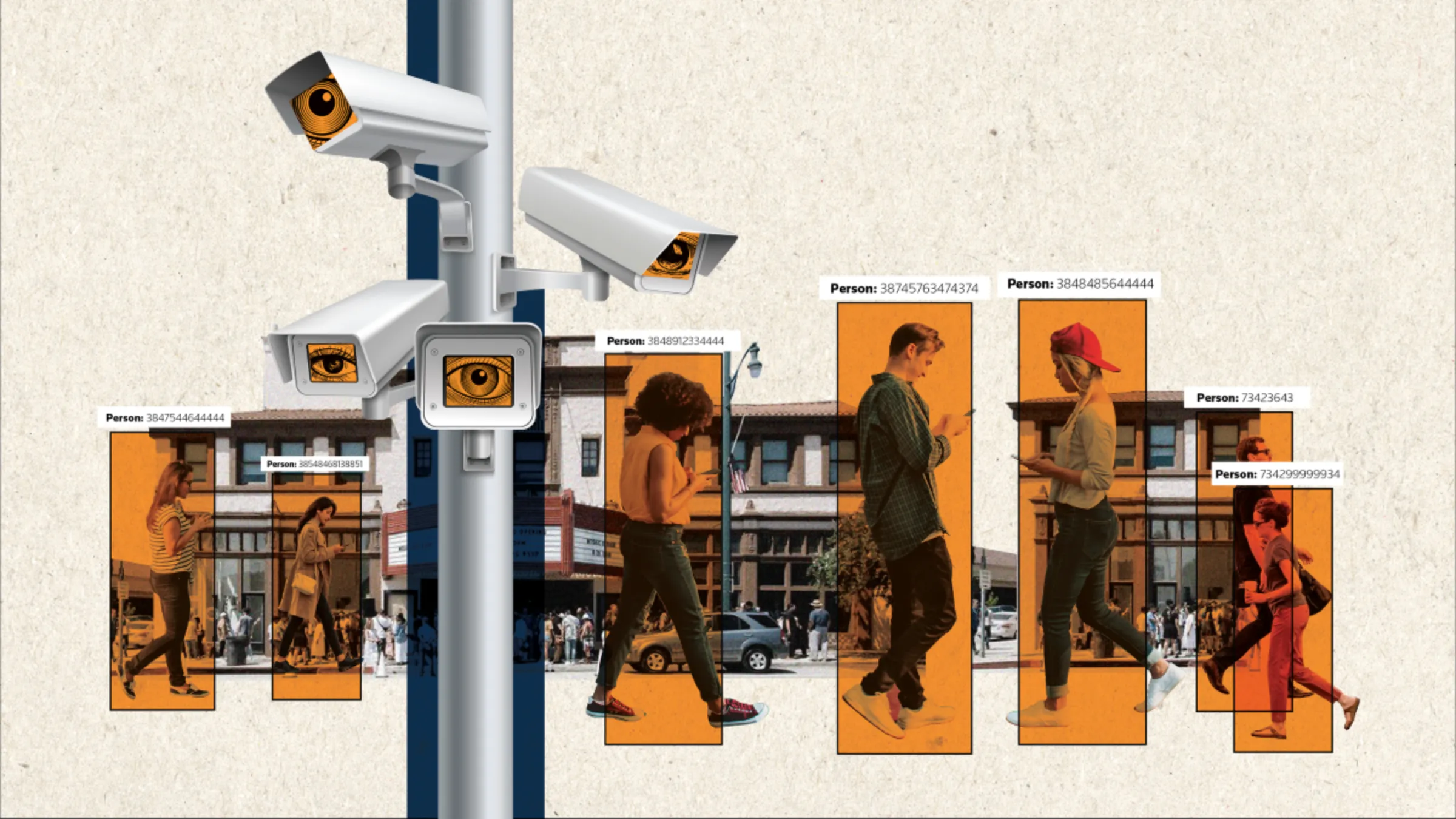

As US cities seek more data in public, can they win trust in tech?

A participant takes part in a “data walk” in Long Beach, California, in October 2022. The city of Long Beach/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

What’s the context?

Can transparency make citizens more comfortable with data-gathering in public spaces? A pilot in U.S. cities seeks to find out

- Cities trial public icons, feedback option

- Framework explains data use and benefit

- Cities also increasingly grapple with private deployments

Over the past year, Karen Reside has walked across Long Beach, California, searching out the cameras, censors and other data-gathering devices that she says have proliferated on her city's streets.

The results have been startling.

"I hadn't realized how many cameras had been added," Reside told Context. "It was very eye-opening."

Participants on the walks, co-organized by the city as part of a broader effort to create municipal data privacy guidelines, even found tech devices on manhole covers.

"We started to realize there was no sense of privacy anymore, anywhere," said Reside, 73, president of a group called the Long Beach Gray Panthers that advocates for the elderly.

Ryan Kurtzman, Long Beach's smart cities program manager, said that "cities in general don't do a great job with communicating with residents about these technologies that are everywhere."

"When we go to the supermarket, we expect to see a nutrition label about what food we're consuming. We should have the same right to know what specific technologies are consuming about us as people as we go about our day-to-day lives."

Now Long Beach and a handful of other cities are testing how to do that – putting up icons with QR codes near cameras or air quality censors to explain what they are, what data is being collected and why, and give passers-by a way to offer feedback.

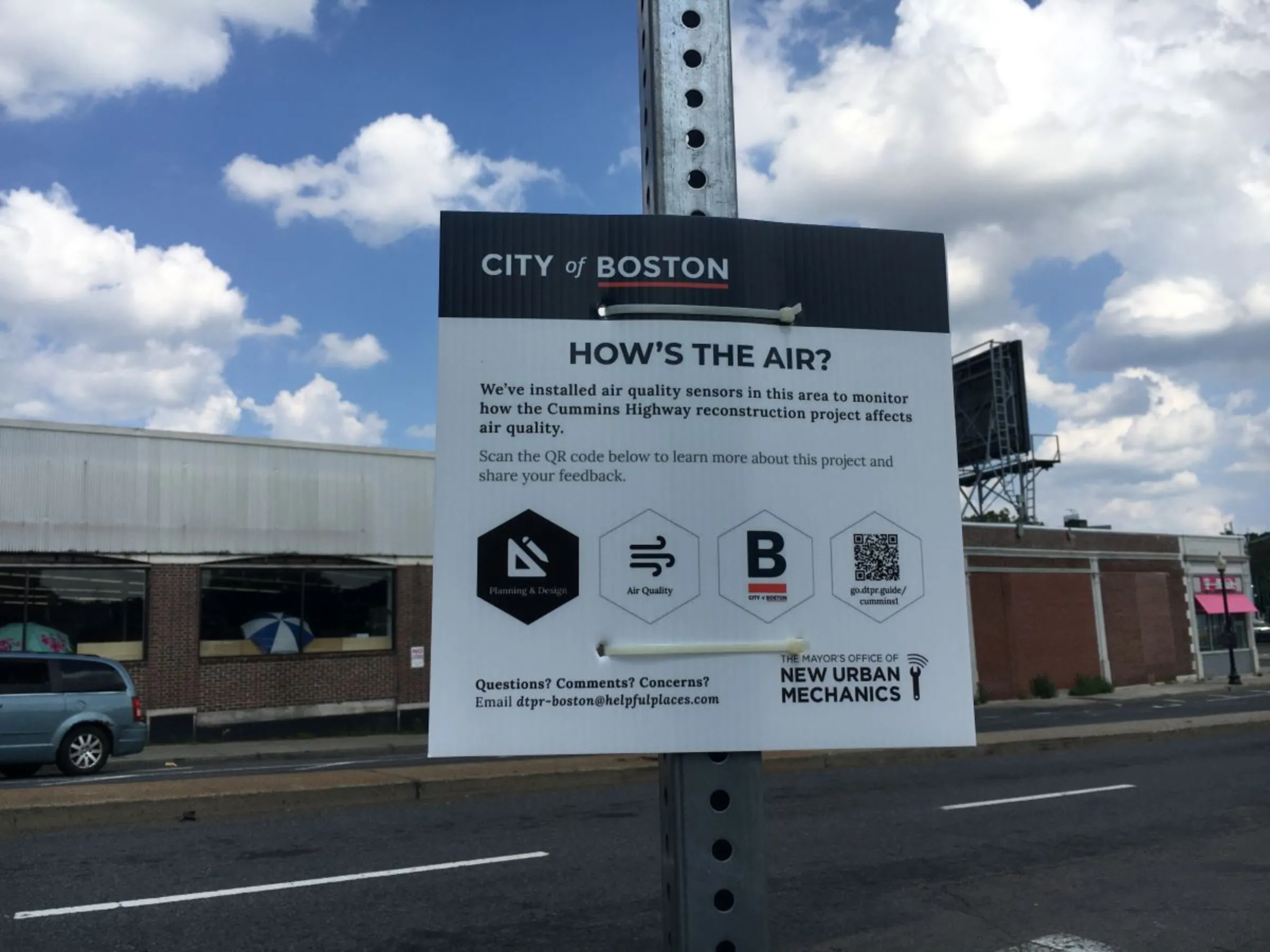

A sign in Boston alerts pedestrians to a nearby air quality sensor. Mayor's Office of New Urban Mechanics/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

A sign in Boston alerts pedestrians to a nearby air quality sensor. Mayor's Office of New Urban Mechanics/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Four cities in the U.S., Canada and France have piloted the Digital Trust for Places & Routines (DTPR) framework over the past year, according to a report this month, which will expand to a handful of other cities in coming months.

"If we think about the increasingly digital worlds we live in – one is the one we travel to consensually when we open a browser or unlock our homes," said Jacqueline Lu, president and co-founder of Helpful Places, the social impact enterprise spearheading the project.

"The other is the one we walk in constantly, where we can't really have an awareness."

While there is a sense that these technologies are being put in place with little accountability or oversight, she said, "what DTPR tries to do is say, yes, we should be acting to limit potential harm" from this tech, but also recognizing its potential benefits.

A sign in Washington alerts pedestrians to nearby data-gathering technology in June 2023. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Carey L. Biron

A sign in Washington alerts pedestrians to nearby data-gathering technology in June 2023. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Carey L. Biron

'It's a balance'

Explaining the value of data-gathering tech in public spaces is complicated given that the benefits are communal rather than individual, Lu said, but helping cities do so can boost residents' ease with the technologies.

That matches up, for instance, with previous resident sentiment in Long Beach, according to surveys that Shannon Lin and Asher Lipman worked on last summer as fellows for the city.

"It's a balance – there are some concerns about their data being used, but if it is used for the wellness of them and the city, there's support for that," Lin said.

The Consumer Technology Association declined to comment on DTPR and efforts to build public trust in such deployments, while other industry groups did not respond to requests for comment.

In October, Washington placed the DTPR icons at five locations, covering technologies including CCTV cameras and automated traffic enforcement, said Stephanie Dock, a program manager with the city's Department of Transportation.

About 20 people per day clicked through to find out about the technologies and indicate how they made them feel – with initial results suggesting about 60% felt happy or very happy, she said.

"A lot of time, the tech we're deploying isn't scary – we do try to think through the privacy considerations," Dock said. "But we don't have a good way of telling the public that's going on."

Boston also deployed the DTPR signs last year around air quality sensors, part of a broader strategy to engage citizens earlier around the use of new technologies, said Kristopher Carter, chair of the Mayor's Office of New Urban Mechanics.

"The tenor of deployment of technology has really changed over the last few years in cities," he said.

"A decade ago it was a Wild West of putting out kiosks, sensors and cameras." Now, local officials are asking, "what's the minimum amount of data and information we need from people to make good decisions in the city?"

Yet some worry that helping residents feel comfortable with certain technologies papers over broader concerns.

"Government data collection documenting identifiable people contributes to an ever-growing digital profile of our comings and goings," said Karen Gullo, an analyst with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, an advocacy group.

"Giving people information about where sensors are in their communities is a long way from participatory governance about whether sensors should be there in the first place."

Third-party developments

Meanwhile, cities are also seeing more data-gathering tech being deployed by companies, said Paula Boet Serrano, project manager with the international Cities Coalition for Digital Rights, based in Barcelona.

"At first it was the city deploying air quality or traffic (monitoring devices), but increasingly it's third parties that are installing sensors, cameras and more," she said.

A report from the coalition last year found that most cities are "not aware of the pervasive nature of commercial sensors".

Amsterdam has begun requiring that companies alert local officials about any public tech deployment, Serrano said, "but many other cities don't have anything".

Strategies such as DTPR can help to reach an eventual balance, she said, "to generate trust around these technologies but also make sure that people have a say in them".

Greater transparency could have an effect on cities' own enthusiasm for collecting data, said Gwen Shaffer, who does data privacy research at California State University, Long Beach.

She co-organized the "data walks" in Long Beach, and is now helping the city expand its DTPR deployment to marginalized areas.

"It's easy for local governments to say yes" to new technologies, "and a lot of times it's not necessary," she said.

"So it will be interesting to see if ... now the city says they will try to limit or use fewer technologies."

(Reporting by Carey L. Biron; Editing by Zoe Tabary.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Facial recognition

- Tech regulation

- Data rights

- Smart cities