What is dark shipping, and why is it dangerous?

A crew member boards a cargo ship in the Port of Montreal in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, May 17, 2021. REUTERS/Christinne Muschi

What’s the context?

Hidden networks of vessels are undermining sanctions, seafarers' rights and the environment while quietly reshaping geopolitics.

A shadow fleet of ships operating in legal and regulatory grey zones delivers much of the world's oil from countries under international sanctions and is linked to other risky or illicit activities that may threaten the stability of global trade.

The dark fleet is no longer fringe. These vessels now represent 17% or more of global oil tanker traffic, according to industry analysts.

Beyond the reach of regulators, dark ships - often old and substandard - put the thousands of seafarers who operate them in danger of labour abuses.

The lack of accountability means seafarers may be deprived of wages, work in unsafe conditions and risk being abandoned at sea. In 2024, more than 3,000 seafarers were stranded on 230 ships, many of which were linked to dark fleet operations.

Here is what you need to know about the world of dark shipping.

What is the shadow shipping fleet, and how is it different from the rest of the maritime industry?

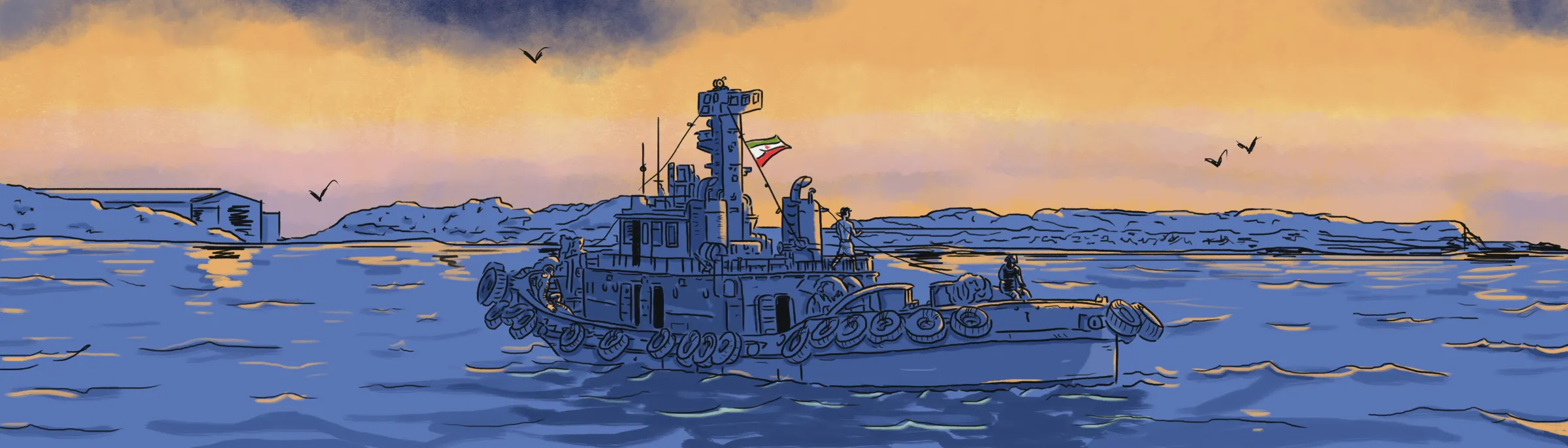

Also known as the dark fleet, these are ships that deliberately conceal their location, identity or cargo to avoid detection by authorities.

Unlike ordinary ships, which keep their transponders on and are obliged to follow international safety and reporting standards, dark fleet ships switch off their Automatic Identification System (AIS), use false registration papers, disguise their ownership through complex corporate structures or physically alter ship markings.

Many of these vessels are poorly maintained and fly flags of convenience from countries with weak oversight of their registered ships. This makes them harder to regulate and more prone to accidents.

While turning off AIS transponders can help ships virtually disappear from regular shipping maps, they can still be tracked using other technology, such as satellite imagery and radar that works despite cloud cover and at night.

Artificial intelligence can also be used to detect ships that loiter near sanctioned ports, make suspicious ship-to-ship transfers or follow routes that do not make commercial sense.

Why do ships go dark?

Companies may turn to dark ships to engage in smuggling, illegal fishing, dumping waste at sea or avoiding port fees. The aim is usually to hide activities that would otherwise be restricted, taxed or punished under international law.

Another major driver is sanctions evasion. Western sanctions on Iran for its nuclear programme and on Russia after its invasion of Ukraine have pushed those countries to rely on the dark fleet to continue exporting oil, according to the U.S. Treasury and international authorities.

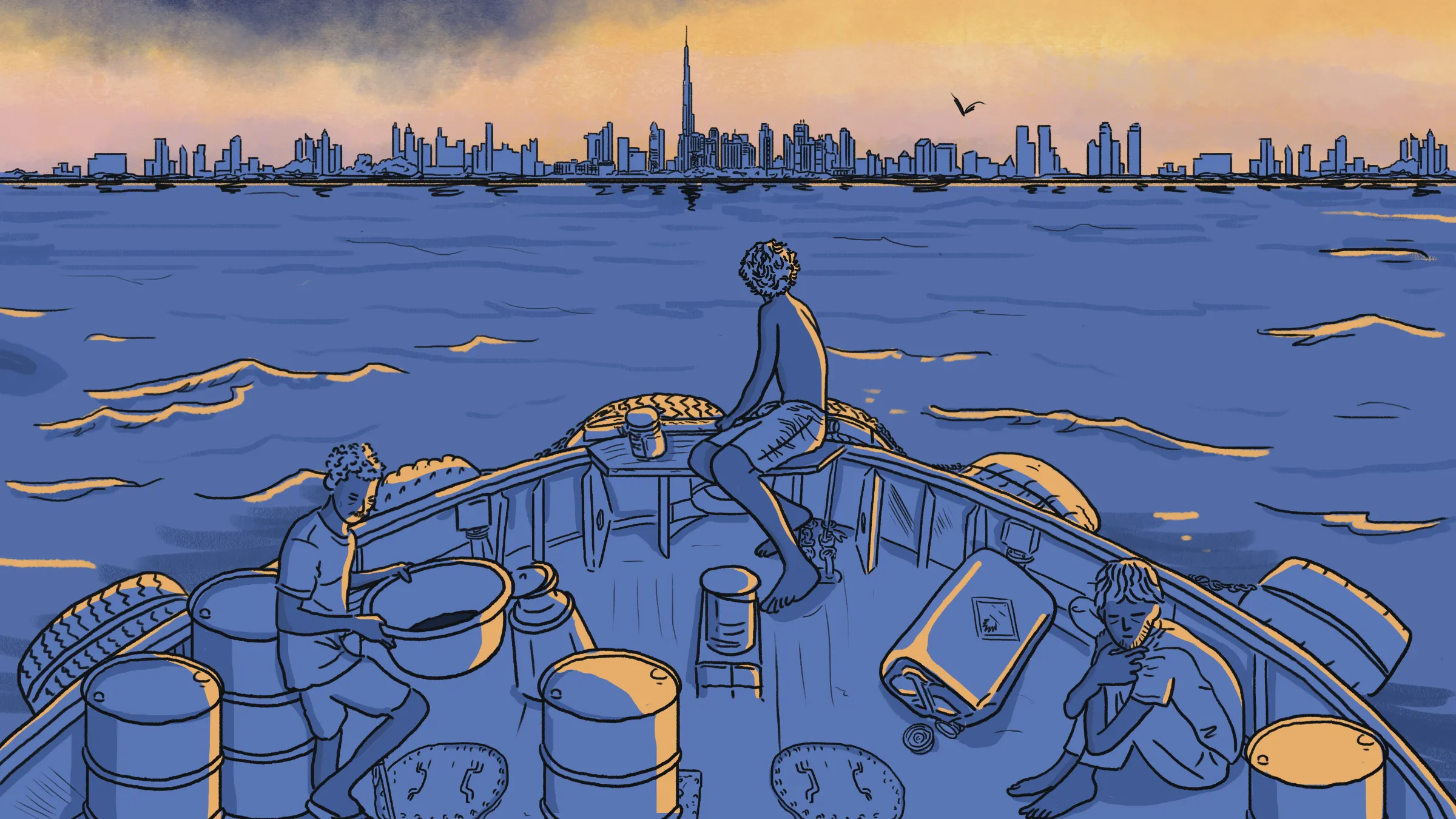

In the Persian Gulf, ship-to-ship transfers of smuggled Iranian oil take place at different hotspots. For example, ships will anchor offshore from Iraq's oil-producing region of Basra, "then fake documentation is produced that states that the cargo is from Basra oil terminals," said David Tannenbaum, director at Blackstone Compliance Services, a consulting firm in Washington.

What risks do dark fleets create?

Shadow fleets pose major risks to workers' safety and the environment. Ships often carry oil or hazardous materials without proper maintenance or insurance, raising the risk of catastrophic spills and collisions, as well as accidents onboard.

The Pablo, a 232-metre-long tanker built in 1997, was suspected of transporting sanctioned Iranian and Russian oil. In 2023, it spilled bunker fuel off the coast of Indonesia's Riau islands, darkening almost 14 square km (5.4 square miles) of the sea's surface.

Three seafarers onboard the Pablo are missing and presumed dead.

Some shipping operators turn to human trafficking to crew their dark vessels.

Traffickers often target people from economically vulnerable communities, luring them with false promises of a legitimate seafaring career and concealing the risks or illegal nature of the work involved.

Aspiring seafarers may be forced to pay illegal recruitment fees to obtain these jobs and face conditions considered a form of forced labour, including overwork, the confiscation of documents and the withholding of salaries.

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Ocean Reporting Network.

(Reporting by Katie McQue; Editing by Ayla Jean Yackley and Amruta Byatnal.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Workers' rights