Forced scamming is exploding - here's why the world needs to act now

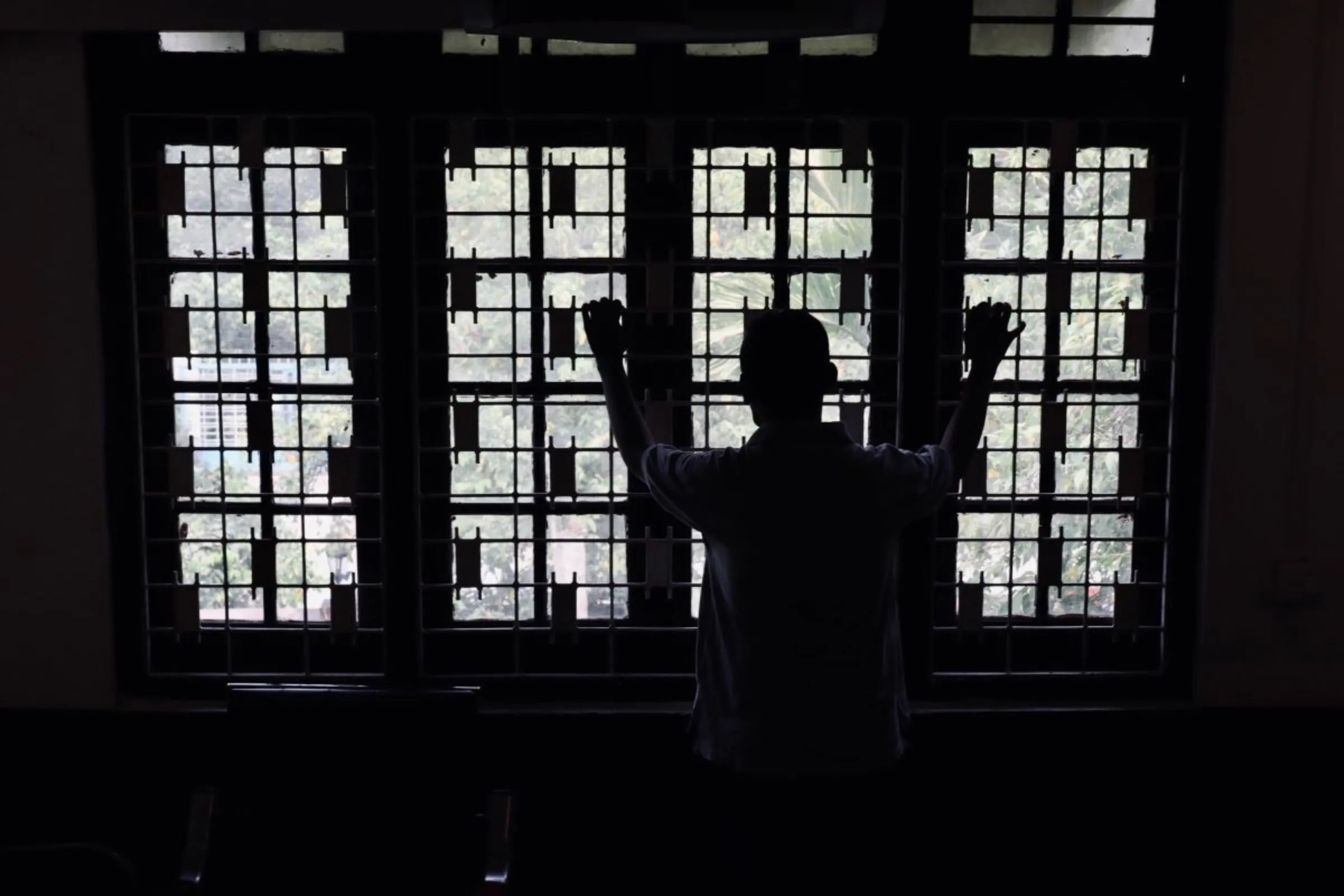

Obscured image of a person who was trapped in forced scamming. International Justice Mission/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Forced scamming is one of the most complex and fastest growing forms of organised crime and modern slavery

By Jacob Sims, senior technical advisor on forced criminality, International Justice Mission.

The UK Foreign Office just announced the world’s first list of sanctioned individuals and companies related to Southeast Asia's exploding forced scamming epidemic.

Forced scamming is one of the most complex and fastest growing forms of organised crime and modern slavery today. This industry is a global threat: transnational crime groups are trafficking victims from all over the world and forcing them to conduct scams under threat of abuse, torture, and murder. According to various UN agencies, the regional workforce scale is estimated in the hundreds of thousands and the annual revenue is in the tens of billions.

Downstream, those targeted by the scams – including UK citizens - are losing life savings. Adding insult to injury, powerful criminals are laundering proceeds into valuable UK assets, with money originally scammed from UK citizens.

Back in 2021, International Justice Mission’s Cambodia team mounted one of the earliest responses to this phenomenon and IJM’s regional counter-labour trafficking programme is playing an active role in the growing global movement to disrupt this abusive industry and bring protection to its victims. IJM’s work globally is focused on building the capacity of local justice systems to protect vulnerable communities from violence.

UK sanctions fall outside of that mandate and are not a part of our approach. Yet, where criminals have become so powerful that local systems can't hold them accountable, transnational levers like sanctions, asset seizures and travel bans can play a helpful role in changing those incentive structures.

So, as I look through the 14 names on the UK’s sanction list and reflect on the horrific stories of abuse we've heard from survivors of forced scamming over the last two and a half years, this feels like a win for justice and accountability globally. It feels like a win for survivors of this abusive industry, people like Gavesh.

Gavesh became wrapped up in this nightmare when he saw a promising job advert on social media for a data entry operator role in Thailand. Upon arriving in Bangkok, he was bundled into a vehicle and trafficked to a guarded compound in Myanmar. The role he had been offered wasn’t real. Instead, he was forced to create fake social media profiles and scam people for up to 16 hours per day.

He recalled that “failure to scam people would mean physical harm or even death. I was beaten by the team leader for failing to hit the quota… There was no way of escaping that place. The compound had walls 10ft high with wires on top. The place was guarded by armed men. Any attempt to escape the compound is a death wish.”

For a survivor of forced scamming like Gavesh, UK sanctions and similar transnational measures offer some hope that the criminals who caused his suffering are now on global governments’ radars and will no longer be able to operate with impunity. Hopefully, the UK’s leadership will catalyse other countries to take a strong stand against the industry.

For these reasons amongst others, sanctions are an important move, but they represent only the first step towards disrupting the organised crime networks driving this brutal industry.

Ultimately, sanctions will only ever target a fraction of the leading criminals. It will fall to local justice systems to bring the majority of perpetrators to justice. Amongst other challenges inherent to this task, significant law enforcement coordination is needed between agencies and countries as this crime type crosses global jurisdictions.

As a coordinated law enforcement response mobilises, it will also be critical to strengthen our ability to disambiguate between the criminals with agency and forced criminals like Gavesh (who are in fact victims). Mass arrests, charges, convictions of scam centre workers will do nothing to disrupt the industry. It will however revictimize the large numbers of people who are engaged in criminal activity against their will.

Additionally, this new flow of trafficking victims is overwhelming already strained social services, which means that there is an urgent need for increased resources to strengthen survivor services.

Lastly, private sector corporations – especially those in tech, telecoms and finance – are inadvertently enabling this criminal activity. As such they hold some of the tools necessary to significantly disrupt its growth. The UK government can and should coordinate closely with the private sector to identify ways to mitigate the harm to UK citizens and deter the facilitation of serious human rights abuses that occur on these platforms.

In short, there’s much work to be done.

IJM commends the UK government’s demonstrated commitment to this issue. I am hopeful that in coming months we'll see more criminals sanctioned and other countries following suit. But this can only be the beginning. This is now a global issue. If we truly aim to disrupt this criminal industry and deter its abuses, it will require a global response.

Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Context or the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Tags

- Disinformation and misinformation

- Content moderation

- Tech regulation

- Data rights

Go Deeper

Related

Latest on Context

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6