"There's no other option" Black, Hispanic families worried by Medicaid cuts

A nurse takes the pulse of a patient inside the East Arkansas Family Health Center in Lepanto, Arkansas, U.S., May 2, 2018. REUTERS/Karen Pulfer Focht

What’s the context?

Historic changes under debate regarding Medicaid threaten healthcare for tens of millions in U.S.

- Medicaid cuts under debate would be largest ever

- Program covers 70 million poor people

- 60% covered come from communities of colour

WASHINGTON - For poor families across the United States, the sense of foreboding over possible major cuts to the government's Medicaid insurance program is worsened by the fact that, for many, no alternatives exist.

Congressional leaders want the issue settled by the end of May, creating a period of limbo for people like Julian Pineiro, a retiree in Florida who has been on Medicaid for a decade, along with his wife.

"I could rely on my family, but other than that there's no other option, and that's the story for all of my neighbours, too," said Pineiro, 78, who lives in a senior apartment building with about 20 other units.

In addition to their regular health checkups, his wife has had two surgeries in recent years paid for by Medicaid, said Pineiro, who worked for years in the warehouse of a department store chain.

"My retirement fund wasn't enough to afford health insurance. If it wasn't for Medicaid, my wife and I would have to choose between putting food on the table and getting the health care and medicine we deserve," he told Context through a translator.

Congressional leaders have said they do not intend to make large cuts to Medicaid, a decades-old insurance program that covers 70 million people with low incomes.

But experts say this would be the only way to pay for the tax and spending cuts that President Donald Trump has said he wants.

Balancing that equation would add up to cuts of $880 million to Medicaid over a decade, 29% of state Medicaid spending per resident, according to KFF, a health policy organization.

Medicaid helps people of all races and ethnicities, but has been particularly important to marginalized communities, said Stan Dorn, director of health policy with UnidosUS, the country's largest Hispanic civil rights organization.

"Folks in these communities are more likely, for reasons of historical discrimination, to have jobs that pay low wages and don't provide health benefits," he said.

Almost 60% of people who are now insured through Medicaid come from communities of colour – some 42 million people, according to a recent report co-produced by Unidos US.

"So, if Medicaid is cut, it will hurt people from all walks of life, but it will hurt communities of colour especially deeply," Dorn said.

Ultimately the decisions would fall to cash-strapped state and local officials to figure out how to backfill the gaps.

"Cuts would blow a hole in our local safety net," said Andrew Werthmann, city councillor in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, who recently co-sponsored a city resolution urging against Medicaid cuts.

"If Medicaid is slashed, more people will delay care until they're in crisis, overwhelming emergency services. Homelessness could spike as families lose health care or disability support."

Health equity

Medicaid has been a political football for decades, but experts say the cuts now being considered would be the largest in history.

The debate comes just as efforts have picked up to address racial health disparities, spurred by the pandemic.

"These disparities come from decades of policies, beliefs and attitudes that are embedded in our systems," said Latoya Hill, a senior policy manager with the racial equity and health policy program at KFF, who recently published on the issue.

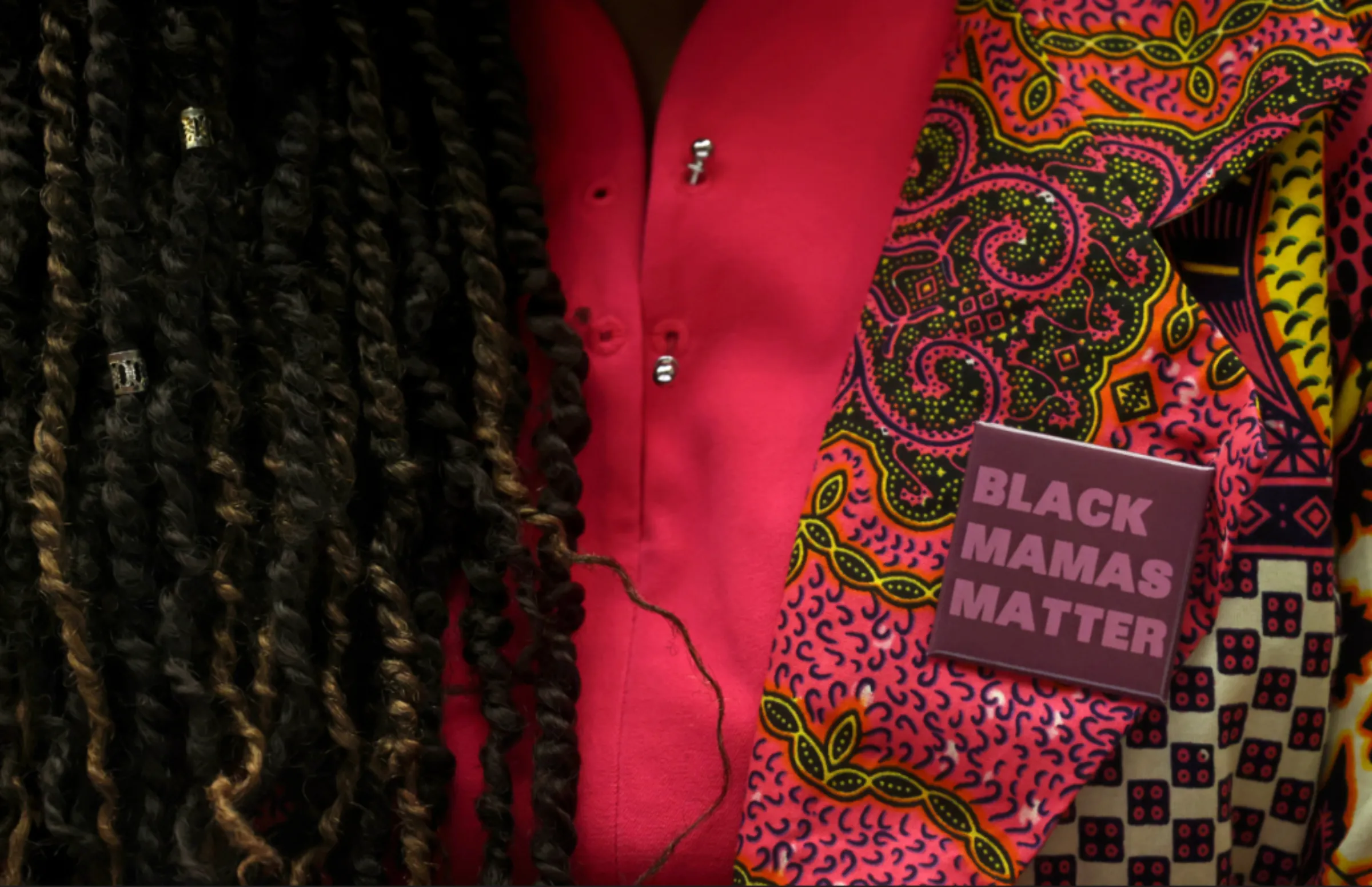

Black women, for instance, experience three to four times the rates of maternal mortality compared with white women, and the Biden administration started to make significant funding available to address such gaps, including through Medicaid.

The Medicaid debate also follows Trump's orders to eliminate diversity, equity and inclusion programs across the government, and mandate English as the country's official language.

Hill said the effects could show up in healthcare in a variety of ways, for instance, in the diversity of practitioners themselves, important for addressing community-specific issues.

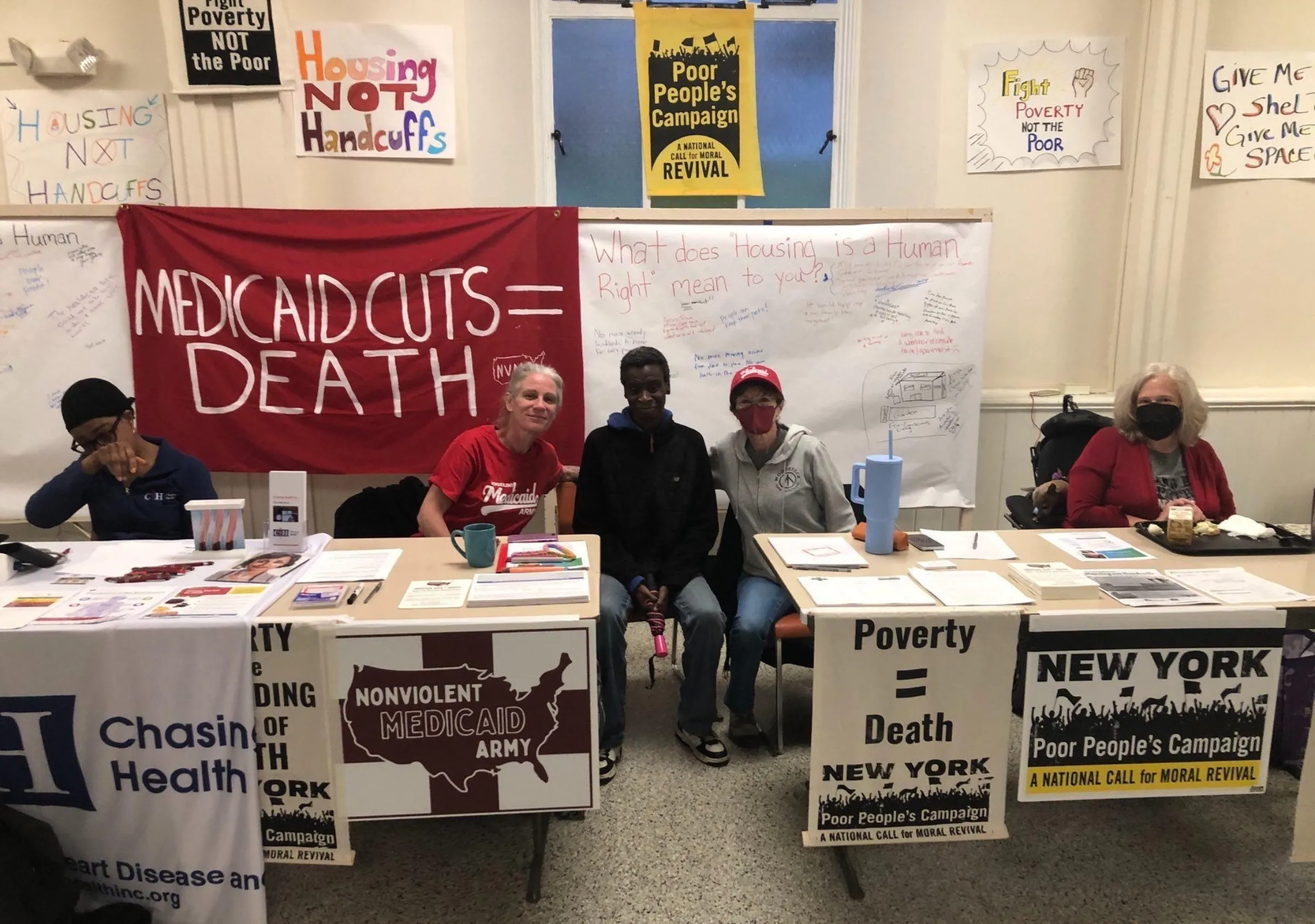

People take part in a free “people’s clinic” in Albany, New York, on September 25, 2024. Nonviolent Medicaid Army/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

People take part in a free “people’s clinic” in Albany, New York, on September 25, 2024. Nonviolent Medicaid Army/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

'Rumor mill'

For now, communities are doing what they can to prepare, and to clarify that no cuts have yet been made.

"There's a lot of rumour mill, misinformation going out," said Rocio "Rosy" Bailey, director of the health access project with Hispanic Services Council in Hillsborough County, Florida.

"Many are hearing that somehow using these safety nets are going to impact their naturalization process," she said. "We're having individuals, out of that fear, drop some of these safety nets without the proper information."

Others are encouraging recipients to see the current policy debate as part of a longstanding effort to shrink Medicaid, and to organize to make systemic changes.

"Who are the poor in the U.S. today? They're people who are on or have been unfairly excluded from Medicaid. That's a huge group of folks," said Nijmie Zakkiyyah Dzurinko of the Nonviolent Medicaid Army, a group that began in Pennsylvania in 2018 and expanded nationally during the pandemic.

The group is now taking part in town halls, putting on "people's clinics" and helping with Medicaid applications and denials.

"It's not just to fight back against this immediate attack, but to get people organized over the long-term, to bring in those who have never organized before," said Dzurinko, co-founder of Put People First! PA, the organization that launched the Nonviolent Medicaid Army.

The current debate over cuts has brought a huge amount of new attention to the issue.

"I've never heard the word 'Medicaid' come out of folks' mouths more," said Kelly Smith, a Medicaid recipient in New York who has worked with the Nonviolent Medicaid Army's people's clinics, offering health monitoring, and an opportunity for organizing.

"Medicaid cuts equals death. I am fortunately on it now, my kid is on it, but we're both terrified because it's so precarious."

(Reporting by Carey L. Biron; Editing by Jon Hemming)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Wealth inequality

- Race and inequality

- Poverty

- Cost of living