U.S. hurricane forecasters losing critical access to government data

People walk among the debris of their family's beach house, following Hurricane Helene in Horseshoe Beach, Florida, U.S., September 28, 2024. REUTERS/Marco Bello

What’s the context?

With the Atlantic hurricane season underway, U.S. Defense Department does about-face on ending data from three meteorological satellites.

- U.S. reverses decision to end meteorological data sharing

- Three satellites to share date till next year

- Data loss would have hindered hurricanes monitoring

LOS ANGELES - Ten months after Hurricane Helene ripped through Shirley Scholl's home in Florida, inundating it with four feet of storm surge and sewage, her family can finally see some rebuilding progress.

Crews working on the skinny island of Clearwater Beach just off the coast have started to elevate the remains of the structure more than 13 feet (4 metres) to meet new federal building regulations in response to the devastating hurricane.

The disaster in September 2024 killed at least 250 people and caused nearly $79 billion in damage, making it the deadliest hurricane in the United States in 20 years, according to the National Weather Service.

"We had to take everything in the whole house down to the studs," said Lisa Avram, Scholl's daughter, who is overseeing the reconstruction.

But as families rebuild from last year's storms, this year's Atlantic hurricane season is underway, with even more risk than before. Forecasters warn it will likely be busier than average, with three to five "major" hurricanes predicted.

However, meteorologists were surprised when the U.S. Department of Defense announced in June it was suspending data sharing from three of its meteorological satellites, cutting the available data that meteorologists use by about half.

After a last minute intervention by the space agency NASA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) announced the service would extend until no later than July 31 and was being suspended to "mitigate a significant cybersecurity risk".

On July 30, the U.S. Navy, which administers the programme the satellites are part of, reversed its decision "after feedback from government partners", and will keep "the data flowing until the sensor fails or the programme formally ends in September 2026", according to a statement.

It has previously noted that Congress voted to end the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) in 2015.

It is a reprieve, albeit a temporary one, for weather forecasters and climate scientists. The data has helped them accurately pinpoint the size, location and intensity of hurricanes for two decades.

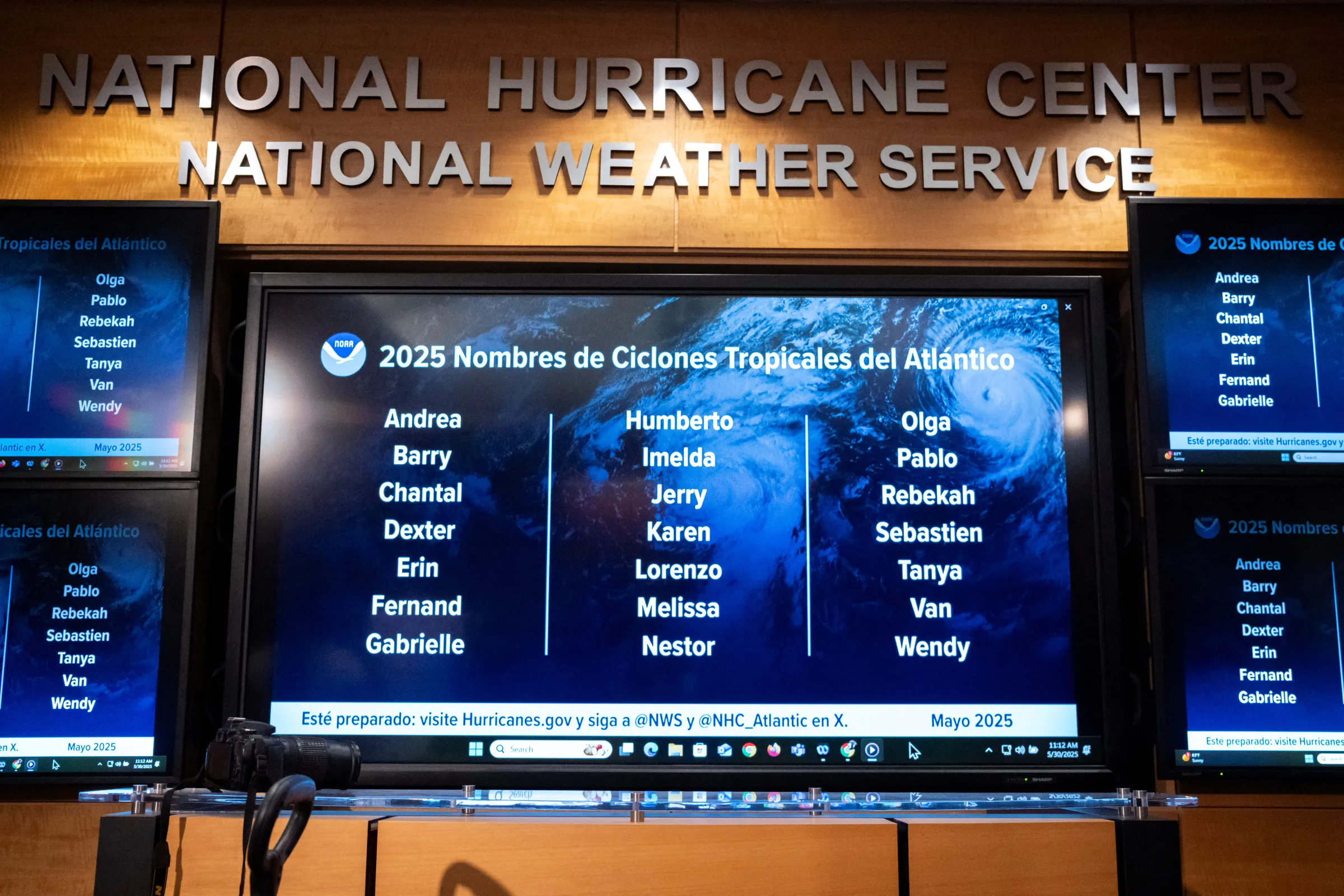

Monitors display the 2025 Atlantic Tropical Cyclones names at the National Hurricane Center (NHC) during a news conference in Miami, Florida, U.S. May 30, 2025. REUTERS/Marco Bello

Monitors display the 2025 Atlantic Tropical Cyclones names at the National Hurricane Center (NHC) during a news conference in Miami, Florida, U.S. May 30, 2025. REUTERS/Marco Bello

"It's all sorts of problematic," said Michael Lowry, a hurricane specialist with television station WPLG in Miami, Florida, and formerly of the National Hurricane Center, part of NOAA.

The data sets, Lowry said, "were really important for telling us how strong a hurricane currently is, but also how strong it might get".

These are not run-of-the-mill satellites tracking things from high above the clouds as seen on radar images, but operate in low polar orbits using microwaves to "see into" a hurricane in ways other satellites cannot, according to Lowry.

Without them, the ability for forecasters to issue early warnings would be hobbled, he said.

"With less time to prepare for a hurricane, people can't evacuate. You have a lot more people and lives that are at risk," Lowry said, adding that emergency management services cannot pre-position resources such as search-and-rescue teams that look for survivors.

The loss of data from the DMSP would mean the amount of remote sensing information forecasters can access drops by half, Lowry said.

With three fewer government satellites available to forecasters, the remaining satellites may only produce information on a strengthening hurricane every six to 12 hours instead of every few hours, giving storms a much bigger window to grow unobserved, he said.

Traditional satellites offer limited detail during the day and produce even less at night.

"The concern is what many in our community would call a 'sunrise surprise,' where you go to bed at eight o'clock at night and it's a tropical storm," Lowry said.

"And we wake up in the morning and it's on the doorstep, and it's a Category Three or Four hurricane," he said.

'Giant loss'

Thousands of miles from the tropical hurricane zone, sea ice is also closely tracked by the DMSP satellites.

Climatologists who study polar sea ice and climate change have used these data sets for decades, said Zachary Labe, a climate scientist at the non-profit research organisation Climate Central.

The idea of losing access this summer was "quite shocking," Labe said.

"I hope that in this case it is an example of effective pushback and having the media and others draw attention to the importance of this data," he said. "I am very happy to see that this data may still continue being available to support ... the most accurate weather predictions."

With the announcement of the extension, scientists have more time to put options in place by the fall of 2026.

"These satellites ... have really told the story of Arctic climate change for the last almost five decades now," he said.

"It's been a real key data for cryosphere science," allowing observation of long-term sea ice variability and trends, he added.

Coastal communities such as those in Alaska rely on sea ice information to help prepare for storms and flooding and make decisions about transportation and hunting.

Labe said other satellites controlled by countries such as Japan have the same capability.

But Japan's systems have not been operating as long, and there would have been "a scramble" this summer to match timelines of different satellites so there was no gap in the record.

Climate scientists need "more data, not less," and the satellites served a wide variety of climate research, he said.

In Florida, Lisa Avram and her family live day-to-day on tenterhooks, and is relieved the data will be there, at least through this year.

Losing satellite information in the middle of storm season seemed like a "seriously dangerous proposition" for herself and other storm survivors who have their houses.

This article was updated on Friday August 1, 2025 at 15:14 GMT to include latest development on government decision to end U.S. satellite program in September 2026.

(Reporting by Rachel Parsons; Editing by Ellen Wulfhorst and Jon Hemming.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Extreme weather

- Adaptation