Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

A view shows trees and vegetation burnt by a major fire in summer 2022, as underground fires continue to burn in Hostens, southwestern France. May 5 2023. Joanna Gill/Thomson Reuters Foundation

As drought-hit France reckons with another fire season, experts see opportunity to better adapt western Europe's largest man-made woodland to climate change

LA TESTE-DE-BUCH, France - The scented stands of pine trees stretching along France's southwestern Atlantic coastline were reduced to charred stumps and stacks of blackened timber by the massive fires that ravaged the tourist hotspots of the Landes forest last summer.

In July and August 2022, more than 30,000 hectares (74,132 acres) of forest went up in smoke - a record since mega-fires hit the region in 1949. The scars in the local community run as deep as those on the landscape.

"There has been a collective trauma," said Patrick Davet, mayor of La Teste-de-Buch, where thousands evacuated their homes as last year's fires threatened to engulf the town of about 26,000 inhabitants.

"There are people who have their bags ready to leave at any moment since last summer," he told Context.

Across southern Europe, an unusually dry winter has left tinder-dry forests at risk of blazes from Portugal to France, raising fears of a repeat of 2022, when 785,000 hectares were destroyed across Europe - more than double the annual average for the past 16 years, European Commission data shows.

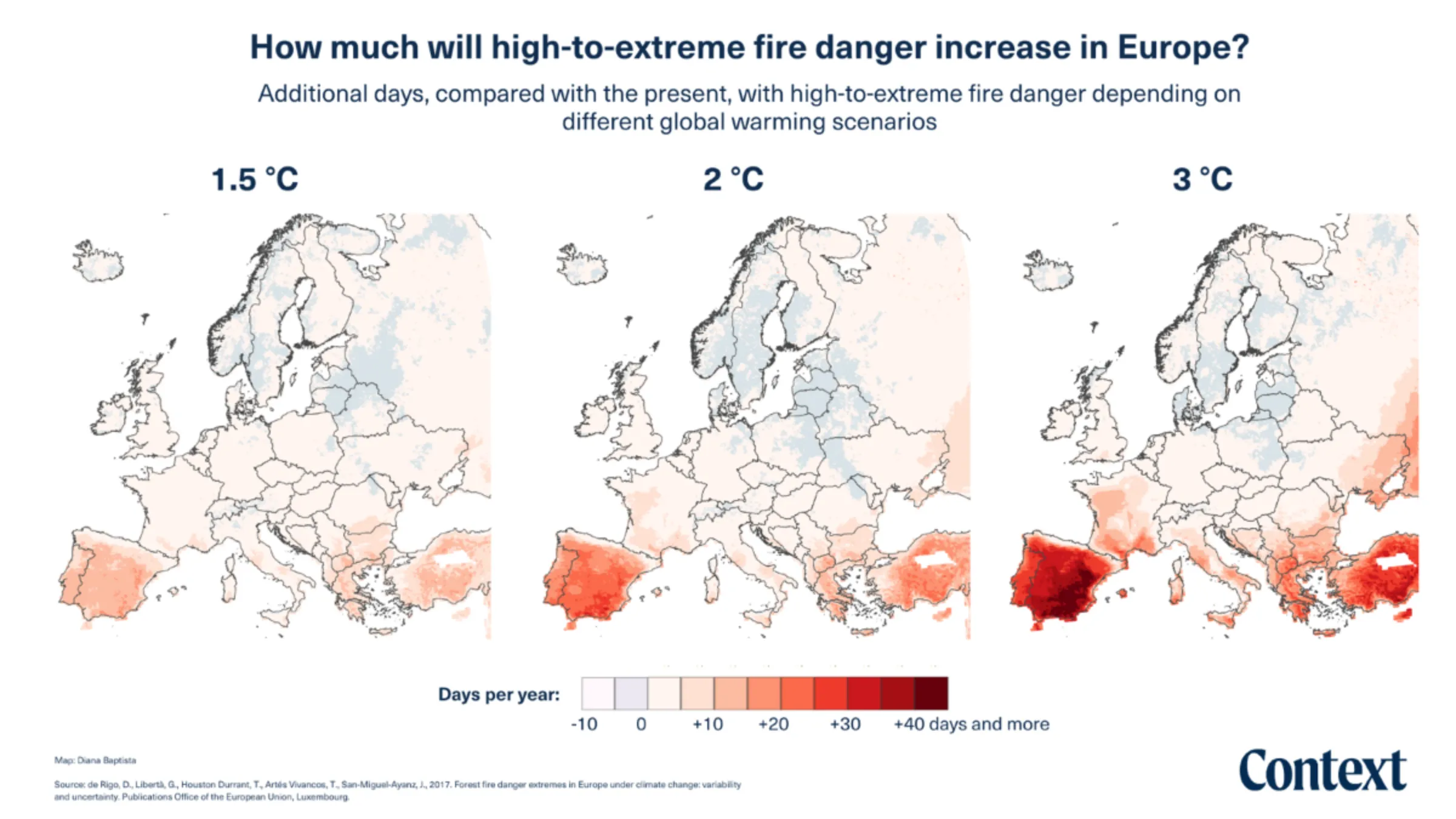

Diana Baptista/Thomson Reuters Foundation

Diana Baptista/Thomson Reuters Foundation

Globally, rising temperatures and land-use change are projected to result in a 50% rise in the number of catastrophic wildfires by 2100, according to the U.N. Environment Programme - and governments around the world are grappling with how best to protect their forests and local communities from the threat.

They also face tough choices over how to replant and regenerate burnt areas, including what tree species to use - and whether to introduce new ones in a bid to make forests more resilient to extreme heat and fire risks.

In the 1 million-hectare Landes forest, western Europe's largest man-made woodland, 87% of the trees are maritime pines, planted here since the rule of Napoleon III in the 18th century, to stabilise sand dunes and prepare the soil for farming.

Today, pine is a key raw material for the construction and paper industries, while its resin is used in varnish and paint. In the Nouvelle Aquitaine region, the forestry sector provides 50,000 jobs and an annual turnover exceeding 10 billion euros ($10.8 billion).

But pine is also highly flammable - and the single-species plantations common in the Landes consist of large stretches of trees of similar age and height, allowing fire to spread easily.

"For four generations, our elders warned (the pine forest) would catch fire, and they were right," said local carpenter Clément Raufaste during a break from repairing fire damage at a restaurant by Cazaux lake.

"Pine resin is like gasoline - once the tree catches fire it lights up like a torch."

Last summer's fires destroyed not just trees but the economic prospects of the tourist business in Nouvelle Aquitaine, one of France's leading holiday destinations.

Beach in Cazaux where wildfires destroyed buildings and restaurants during major wildfires summer 2022, France. May 9 2023. Joanna Gill/Thomson Reuters Foundation

Beach in Cazaux where wildfires destroyed buildings and restaurants during major wildfires summer 2022, France. May 9 2023. Joanna Gill/Thomson Reuters Foundation

In fire-affected zones, the hospitality industry saw an estimated 40% drop in earnings, according to the French sector's union UMIH, and there are worries 2023 could bring another hit.

Eric Wendel, who owns dozens of mobile homes at a campsite by the lake, was lucky as the flames stopped 12 km (7.5 miles) away on the other side, but convincing holidaymakers not to cancel bookings was a daily slog throughout July and August.

"We couldn't afford to lose customers (then) - that's when we make our living," he said.

Five campsites situated along Europe's tallest sand dune - which combined would usually host up to 6,000 people per day during the summer season - were reduced to ashes. They are set to run at around half of their usual capacity this year.

"They're going to have a tough summer, and they will suffer for one or two (more) years," said mayor Davet.

With the peak fire season coinciding with peak tourist season - and 90% of fires caused by human activities such as discarded cigarettes, fireworks or unattended barbecues - educating people is key to preventing blazes, he added.

Measures being put in place this summer include a smoking ban in forested areas, forecasts communicating weather conditions that stoke fire risk, and extra police patrols.

Stopping forests from going up in smoke is key to protecting people and incomes - but also to cutting planet-heating emissions, as trees release the carbon they store when they burn.

Last year's wildfire emissions in Europe amounted to 6.4 megatonnes of carbon, roughly equivalent to the annual emissions of 5 million cars, according to the EU's Copernicus atmospheric monitoring service.

Yet while there are ways to ease the threat in the short-term, debate about how to make forests safer in future rages on.

Last July, French President Emmanuel Macron announced a major reforestation plan that aims to plant 1 billion trees over the next decade, based on species and locations enabling forests to better withstand climate-driven threats, including wildfires.

Since then, "everyone has had an opinion on how to replant", said forestry expert Christophe Orazio, who heads the European Planted Forest Institute near Bordeaux.

In the Landes, the arguments turn on whether to let the forest regenerate naturally and ending the dominance of pine.

Conservationists want efforts to tackle problems they blame on industrial forestry, which favours single-species pine plantations, "meeting the needs of the timber market" at the expense of the environment, said Siim Kuresoo, a Brussels-based campaigner with FERN, a Dutch forest protection NGO.

Replanting monocultures of maritime pine means wildfires will continue to happen, he said. "It's not a question of if, but when and how severe," he added.

Lessons on how to reforest, meanwhile, can be found a two-hour drive south in Anglet, where 165 hectares burned in 2020.

Antoine de Boutray, director of France's National Forestry Office (ONF) in the Pyrenees-Atlantic region, worked on the replanting using cork oak and maritime pine, completed in March.

Regenerating the forest with a mix of species makes it more fire-resilient, as different types of "fuel" slow the spread of the flames and varied moisture levels reduce flammability, he explained.

"Biodiversity is our main ally in adapting forests to climate change - and the forestry industry will come to the same conclusion," de Boutray said.

Local forestry business Planfor, which specialises in pine, helped the ONF replant some of the charred forests.

The head of Planfor's tree nursery, Jean-Marc Bonedeau, agreed that pushing the sector towards greater biodiversity will be a win-win for the local economy and the environment, saying he sees a willingness to change among the company's clients.

"But you have to call a spade a spade - if there are no financial incentives, you won't achieve biodiversity," he said.

Economic innovation could also play a role in boosting local resilience to forest fires, said La-Teste-de-Buch mayor Davet.

For example, planting grape vines around the forest edges would introduce more fire breaks into the landscape, he noted.

"In the past, there were vineyards (here) - even if it didn't make for a great wine," he quipped.

Returning to present-day worries, Davet took a more serious tone as he recalled the lack of rain over winter and the hot summer days ahead, saying local people are scared - but stoic.

"Fear is only helpful when it protects us - so we remain vigilant," he emphasised.

(Reporting by Joanna Gill; Editing by Megan Rowling and Kieran Guilbert)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles