The declaration, championed by South Africa's presidency, represents both a symbolic and a practical step.

G20’s clean air declaration could be a turning point - if we act

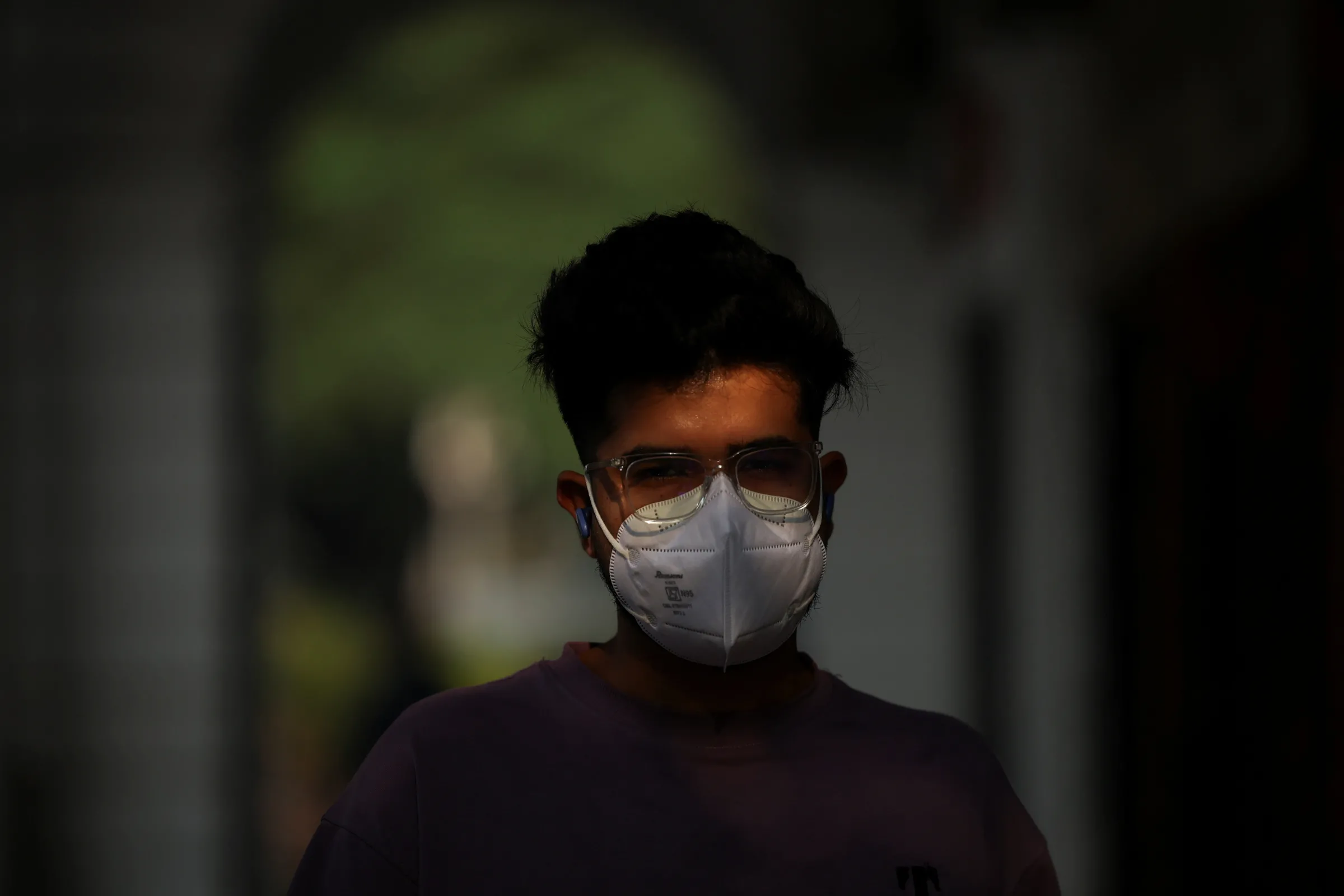

A man walks with a face mask on a smoggy morning after the air quality dipped, partly due to the use of firecrackers during Diwali in New Delhi, India, October 23, 2025. REUTERS/Anushree Fadnavis

G20 ministerial declaration on air quality could bring real change if we embed clean air into development projects and priorities.

Jane Burston is the CEO of the Clean Air Fund.

As the United Nations turns 80, much attention has focused on the state of global cooperation.

Many conclude that the multilateral system is unravelling - or at the very least, fraying at the edges. It seems increasingly characterised by disagreement, divergence, and disruption.

Against this backdrop, finding common ground on shared priorities has become fraught but ever more necessary. Last month, in Cape Town, something unexpected happened: the world's largest economies reached a rare agreement on an environmental issue.

For the first time in the forum's history, G20 governments adopted a ministerial declaration on air quality.

In a world where consensus is increasingly elusive, 20 of the world's largest economies found agreement on something that should never be controversial: the right to breathe clean air. They recognised the need for joint action on data sharing, technology transfer, capacity building, and finance to tackle a crisis that kills 7.9 million people each year.

Symbolic and practical

The declaration, championed by South Africa's presidency, represents both a symbolic and a practical step.

It shows that countries can still unite around air pollution even when broader global agreement on environmental issues can be challenging.

Within the wider global context, that kind of agreement should be celebrated, but the real test is how to deliver when development budgets are under such sustained pressure.

At present, only around 1% of international development financial assistance is allocated to projects with a specific aim to improve air quality — a pitifully small amount compared to the one in eight deaths worldwide caused by air pollution.

But there is good news - data from the Clean Air Fund’s latest State of Global Air Quality Funding report shows that in 2023 investment in projects that achieved air quality improvements alongside their primary objectives rose 7% to $29 billion, spanning sectors from energy to transport to urban development.

These projects demonstrate a crucial point: smarter project design can multiply benefits without multiplying costs.

Consider public transport schemes that cut traffic and emissions while improving access to jobs — like the widespread electrification of bus fleets in Breathe Cities such as Mexico City and Jakarta.

Or energy access projects that replace diesel generators with cleaner alternatives — improving air quality while delivering reliable, cheaper power.

For example, India’s Energy for Health programme is replacing diesel in 25,000 clinics with solar power. These examples prove that economic growth and environmental health can advance together when projects are designed with both in mind from the start.

Embedding air quality

The Cape Town Declaration provides the political pathway needed to embed this logic across the development system.

On a practical level, the declaration recognises the importance of promoting open and reliable air quality data and supporting air quality monitoring where it doesn't currently exist.

This directly addresses a fundamental barrier: 36% of countries, representing nearly one billion people, are not currently monitoring their air quality. Only one quarter of countries provide full and easy public access to useful air quality data.

South Africa has also committed to convening a technical workshop amongst G20 members, paving the way to institutionalising air quality as an ongoing G20 work stream.

The Cape Town Declaration provides the political pathway needed to embed this logic across the development system.

The path forward requires neither new institutions nor massive budget increases. But it does demand a shift in how development projects are conceived and evaluated.

Development banks are already considering how to embed air quality into their operations — from policy to project design.

The Cape Town Declaration provides an opportunity to build on that progress. Many are exploring how to integrate clean air as an explicit objective across development and climate projects, using tools such as the Air Quality Toolkit for Development Finance Institutions to support integration throughout project design and implementation.

They are also working to make air quality an institutional priority, embedding it within policies, staff training and project development so that cleaner air becomes a consistent outcome of good development practice.

The G20 has provided focus and momentum. The world's largest economies have agreed that air quality matters.

Now, through the development finance system, they must change how projects are designed, evaluated and implemented. At Clean Air Fund, we will transparently track whether the gap between commitment and delivery narrows or widens.

The declaration has created political space for action. Whether that space is used well will determine whether 2025 marks a genuine turning point in the fight for clean air.

Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Context or the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Tags

- Fossil fuels

- Climate policy

- Climate and health

- Climate solutions

Go Deeper

Latest on Context

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

Most Read

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5