A year on, Afghans hide out fearing death by data

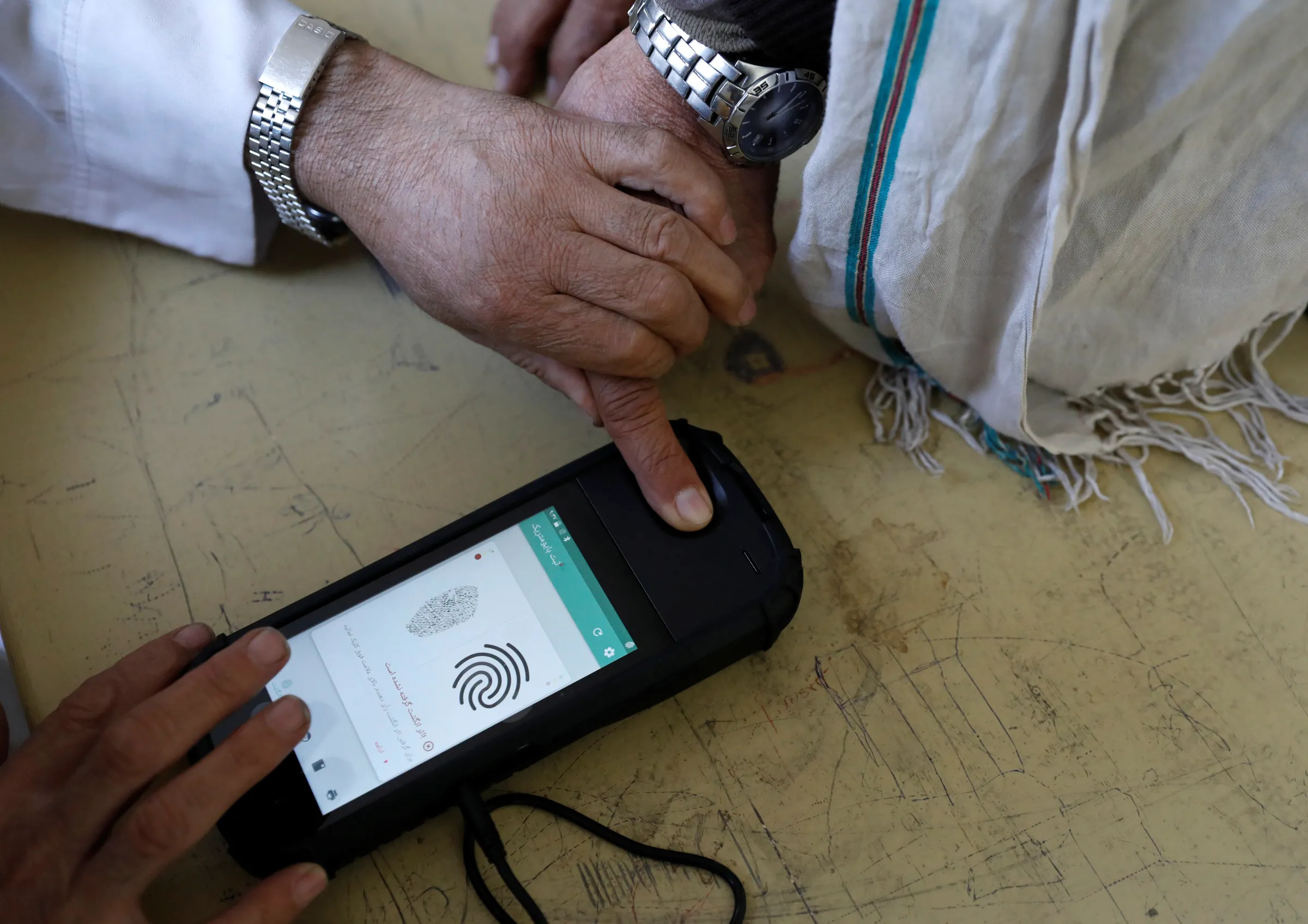

An election worker takes a picture by biometric device in the presidential election in Kabul, Afghanistan September 28, 2019. REUTERS/Mohammad Ismail

What’s the context?

A year after the Taliban takeover, thousands remain in hiding, fearful that biometric data can be used to track them.

- Thousands of Afghans lie low, afraid of detection

- Taliban has access to payroll data, digital ID systems

- Donors, aid agencies fail to secure systems, activists say

Sadaf was at work last year at the attorney general's office in suburban Kabul when her sister rang with news that the Taliban had entered the Afghan capital, and begged her to race home.

"Cover your face! And don't tell anyone where you work," her sister said, her voice shaking with fear.

Sadaf didn't know it then but this was the start of exile within her own country, a life of lying low to avoid death by data. Like thousands of Afghans, she has spent the past year hiding out in a series of safe houses, hoping to evade her digital trail and prevent the Taliban tracking her family.

When her sister broke news of the takeover, Sadaf grabbed her bag and rushed from the office, pulling her headscarf low over her face and tucking her office ID into her shoe.

Outside was chaos.

Streets were jammed with vehicles and people running in every direction, desperate to flee. After walking part way home, Sadaf hitched a ride and made it to her house two hours later.

She quickly hugged her three children, then shut herself in the bedroom, gathered all her identity papers and any documents related to work, and burnt the lot in the bathroom sink.

"I was very scared," said Sadaf, who had worked at the government office for more than 25 years - over half her life.

The 48-year-old, who asked that her last name not be used, knew only too well the danger she faced.

The Taliban had previously bombed their vehicles; Sadaf was injured in two of those attacks and had lost several colleagues.

"I didn't want anything to fall into the hands of the Taliban," she said by text message from an undisclosed location in Afghanistan.

A week after the Taliban took over, men knocked on Sadaf's door and spent hours searching her home. They knew where she worked, and left with a warning that they were watching.

The next day, Sadaf packed her belongings and fled, along with her children and husband, a carpenter. They have been in hiding ever since, lodging with relatives and friends, and never staying anywhere for more than two weeks.

"I am in danger because of my job," said Sadaf.

Taliban members take pictures with their mobile phones during the Taliban flag-raising ceremony in Kabul, Afghanistan, March 31, 2022. REUTERS/Ali Khara

Taliban members take pictures with their mobile phones during the Taliban flag-raising ceremony in Kabul, Afghanistan, March 31, 2022. REUTERS/Ali Khara

Digital danger

Sadaf is among the tens of thousands of Afghans - including former government officials, judges, police and human rights activists - who remain in hiding one year on, fearful of being tracked with digital ID and data systems that the militants gained with regime change.

In the past year, human rights groups and the United Nations have documented the killing or enforced disappearance of hundreds of former members of the security forces, as well as journalists, judges, activists and LGBT+ people.

A Taliban spokesman did not respond to a request for comment.

Like many poor nations, Afghanistan pushed to digitise its data in recent years with funding and expertise from the World Bank, United States, European Union, the United Nations' refugee agency (UNHCR), World Food Programme and others.

One such programme is the digital ID system known as e-Tazkira, which holds a wealth of personal and biometric data including a person's name, ID number, place and date of birth, gender, marital status, religion, ethnicity, language, profession, iris scans, fingerprints, and a photograph.

The ID is needed to access services, jobs and to vote. But it also exposes vulnerable ethnic groups, and people who worked in government or with foreign agencies, rights groups say.

"Everyone is vulnerable," said Aziz Rafiee, executive director of the non-profit Afghan Civil Society Forum, who gets hundreds of desperate messages every day from Afghans in hiding.

The systems were "a big mistake right from the beginning".

An election official scans a voter's finger with a biometric device at a polling station during a parliamentary election in Kabul, Afghanistan, October 20, 2018. REUTERS/Mohammad Ismail

An election official scans a voter's finger with a biometric device at a polling station during a parliamentary election in Kabul, Afghanistan, October 20, 2018. REUTERS/Mohammad Ismail

"In a country like Afghanistan, there is always the possibility that the information would end up in the hands of terrorists, and you could be killed," said Rafiee, who did not apply for an e-Tazkira, fearing this very outcome.

Earlier this year, Human Rights Watch confirmed that the Taliban controlled payroll data of the government and the supreme court, and biometric systems of the police and army, and those who worked with foreign governments and aid agencies.

"For those in hiding, there is no way to avoid detection because the Taliban is carrying out identity checks - with photos, fingerprints, iris scans - at checkpoints," said Belkis Willie, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch.

"So people are not able to leave the houses they are hiding in. In addition, anyone who goes to the passport office to get their passports to try and leave the country - their identity would be very clear to anyone," she said.

"It really isn't possible to avoid detection."

Life and death by data

Advocates for biometric registration say it enables more accurate counts and identification of people in need, ensures more efficient aid delivery, and helps prevent fraud.

But critics say registers can be misused for profiling and surveillance, and many exclude the most vulnerable of people.

The events in Afghanistan have underscored the risks of ID systems that are built without considering the possible impact on human rights, and without safeguards to prevent abuse, said Raman Jit Singh Chima at Access Now, a digital rights group.

Over the past year, digital rights groups have called on aid agencies, foreign donors, and telecom and tech companies to rethink how they gather biometric data, and to secure their systems to prevent harm.

But this has not happened, said Chima, a policy director.

"Digital ID programmes with grave implications for human rights are still being implemented, or encouraged, even in high risk or crisis hit environments," he said.

And in Afghanistan, Sadaf is still in hiding.

"Lack of employment and poverty on the one hand, and fear on the other hand, has made my life very difficult," Sadaf said.

"I wish this was a nightmare and that I could wake up."

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Consumer protection

- Digital IDs

- War and conflict

- Tech and inequality

- Tech regulation

- Social media

- Data rights

- Corporate responsibility