“I’ve seen hell”: Inside the global crisis of seafarer exploitation

Seafarers prepare to dock a Russian missile cruiser in Metro Manila, Philippines, January 6, 2019. REUTERS/Eloisa Lopez

What’s the context?

Seafarers are the backbone of the global maritime industry, but they're often illegally recruited, scammed into dangerous work and then abandoned at sea.

- Maritime shipping industry has 1.8 million seafarers

- Young seafarers are lured into dangerous work, then abandoned on ships

- A reliance on flags of convenience raises risk of the practice

NEW YORK - When coast guard officers boarded junior seafarer Omkar Pawar’s ship off of Trinidad and Tobago in 2020, one of them pointed a gun at his face.

“They searched the ship. After two days, they found 450 kilograms of cocaine in the tank,” said Pawar.

Pawar and the rest of the crew were jailed and interrogated in a Trinidadian detention center for 15 days. The ship’s captain and second officer were later prosecuted.

Pawar, who was 20 at the time, had no knowledge of the smuggling operation and was never charged. Still, he was detained at an immigration center for four months before being deported back to India.

His parents, who are farmers, scrambled to raise money to bring him home. Pawar was already in debt having borrowed $2,400 to pay recruitment fees for what he thought was the start of a promising seafaring career.

“I felt so bad,” he said. “Before this happened, I never imagined I’d be jailed.”

Pawar is one of thousands of young seafarers lured into dangerous or illegal maritime work, often through recruitment scams or misrepresented job offers. Many end up unpaid, detained or trapped aboard abandoned vessels for months, even years.

Abandoned at sea

Context interviewed maritime industry experts and 38 seafarers working on merchant vessels for this story. Their accounts reveal a growing problem of abuse, neglect and impunity.

An estimated 1.8 million seafarers are the backbone of the world’s maritime shipping industry, which accounts for 80% of global trade, including 90% of energy.

Many are routinely exploited, working under dangerous conditions with little recourse. And they are increasingly at risk of abandonment, left on board vessels after a shipowner fails to cover repatriation costs, provide essential support or pay wages.

In 2024, incidents of abandonment surged to a record high: 3,133 crew were deserted by shipowners, up 87% from the previous year, according to the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF). Many more cases likely go unreported, particularly when seafarers are stranded without internet, the means or autonomy to contact the authorities, according to ITF representatives.

The problem is only getting worse. Data released by the ITF in May showed that vessel abandonments have surged nearly 33% to 158 cases this year, up from 119 at the same point in 2024. More than 1,500 seafarers have requested assistance from the ITF.

Opaque company ownership structures and a reliance on flags of convenience - when ships are registered in countries with the most lenient labour laws and oversight - contribute to the practice. Popular flags of convenience include Panama, Liberia, UAE, Palau and Tanzania, according to the ITF.

While the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC) of 2006, known as the Seafarers’ Bill of Rights, sets global standards for conditions at sea, its enforcement falls largely to flag states and local port authorities.

“Unpaid wages are one of the biggest issues we see,” said Josh Messick, executive director of the Baltimore International Seafarers’ Center, an organisation that provides support to seafarers whose vessels dock at the Port of Baltimore in the United States. It also investigates ships for signs that the MLC is not being upheld.

“Their hours are logged incorrectly. They work overtime and don’t get paid for it. In a few months, they can lose thousands of dollars,” he said.

Such abuses often go unrecorded, because seafarers fear that filing complaints with the authorities may trigger their dismissal and leave them blacklisted from other work, said Chirag Bahri, operations manager at the International Seafarers' Welfare & Assistance Network.

Trapped in debt

Many of the seafarers interviewed for this story said they were required to pay illegal recruitment fees, often thousands of dollars, to secure jobs. These fees, banned under the International Labour Organization, can trap workers in debt bondage, making them more vulnerable to abuse and less likely to report violations.

The rise of unregulated ship management companies, which are contractors that run vessels on behalf of owners, has also fueled abuse, according to industry insiders.

“These companies are often run by people with no technical knowledge,” said Cris Partridge, managing director of Abu Dhabi-based consultancy Myrcator Marine & Cargo Solutions. “They take a massive fee, rip suppliers off and leave the ships falling apart.”

The UAE is a hub for global shipping companies, but has not ratified the MLC. The country is also accused of maintaining poor labour protections for migrant workers.

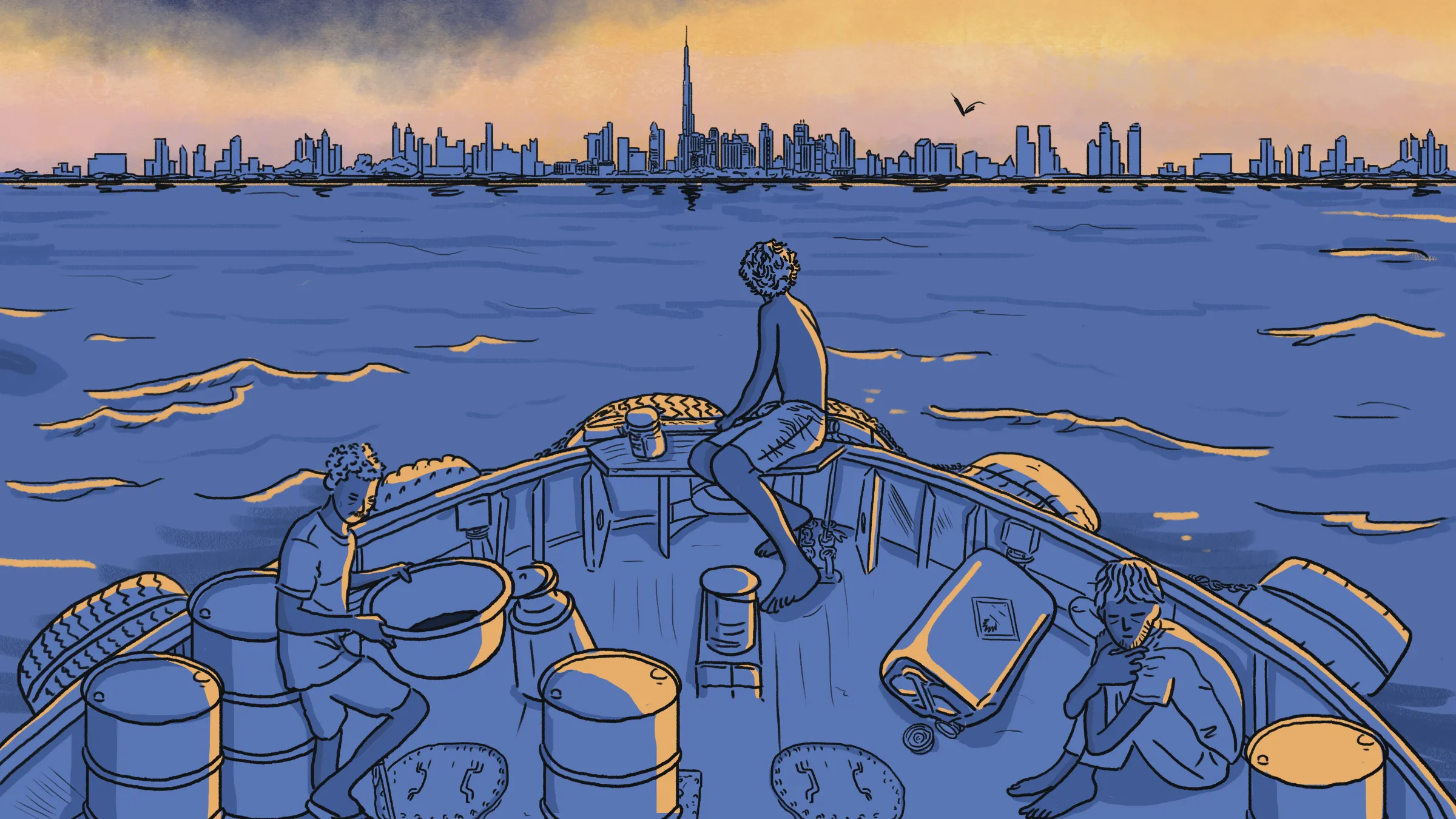

Vinay Kumar, a second engineer from India who worked on merchant vessels, joined the crew of a tanker run by a UAE shipowner in 2019. When the company ran into financial trouble, it stopped paying salaries, Kumar said, and he and four others were trapped on board for 21 months three miles off the Dubai coast.

“We didn’t have enough fuel to cook or run air conditioning. We took showers using sea water,” he said. “We were like slaves.”

With no electricity for a month, the crew depended on charities to survive. In January 2021, the vessel ran aground during a storm. Only after the ship was sold were the men allowed to go home, with just 70% of their owed wages.

“I don’t want to go back to sea again,” Kumar said. “I’ve seen hell.

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Ocean Reporting Network.

(Reporting by Katie McQue; Editing by Amruta Byatnal and Ayla Jean Yackley.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Workers' rights

- Corporate responsibility