On perilous Darién Gap trek, migrants risk all for American dream

What’s the context?

Betting on a brighter future in the United States, record numbers of migrants are crossing the Darién Gap - a treacherous stretch of rainforest straddling Colombia and Panama

Five-months pregnant and lugging a heavy backpack through a lawless stretch of Colombian rainforest, the migrant woman from Angola says "no" for a second time to the jungle porter offering to carry her bag for $20.

"It'll get harder, more mountains ahead," the burly local man warns her at the start of the 60-mile (96-km) trek through the wilderness to neighboring Panama. But she shakes her head and trudges forward along the steep muddy path.

In front of them and behind, a straggly column of dozens of men, women and children weaves its way into the Darién Gap - a perilous jungle route without roads that is being used by record numbers of migrants determined to reach the United States.

A Venezuelan migrant walks in socks alongside a child as they walk along a muddy path through the Colombian jungle bordering neighboring Panama at the start of a seven-day trek. Darién Gap, Colombia, July 27, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

A Venezuelan migrant walks in socks alongside a child as they walk along a muddy path through the Colombian jungle bordering neighboring Panama at the start of a seven-day trek. Darién Gap, Colombia, July 27, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Some hold babies and toddlers, others machetes to defend themselves from snakes, but many are poorly equipped for the seven-day trek during which at least 51 migrants died or disappeared last year, according to the U.N. migration agency.

The dreams and hopes of migrants from three continents converge in this humid cauldron for the coming days, bound together by a shared zeal - and the same destination.

Among the group are two young brothers from a Nepalese farming family. Using their small plot of land as security, their parents raised a $6,000 loan to pay for the brothers' journey in search of work in the United States.

There are also destitute Venezuelans fleeing years of political and economic chaos, a former Congolese boxing champion and young men driven from their homes by conflict in Cameroon and the Taliban's return to power in Afghanistan.

Many initially spent years in Brazil, among them dozens of Haitians who fled the Caribbean nation after a devastating earthquake in 2010.

Several of the African migrants said they had found work building the stadiums for Brazil to host the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics, but that finding well-paid jobs had since become difficult, prompting them to embark on the journey north.

A record 133,000 people crossed the Darién Gap last year, including 29,000 children, according to Panamanian authorities.

And in the first four months of 2022, the number of migrants and asylum seekers crossing the Darién almost doubled when compared to the same period last year.

In August alone, a record 32,000 migrants traversed the Darién, up 40-fold from the same month last year, according to Human Rights Watch.

Whether fleeing poverty or war, the dream of a better life, good jobs, and the chance to send back money home to relatives left behind pushes them to embark on the journey despite the considerable dangers.

Drenched in sweat and carrying a bag with a tent and canned food, Abdu, a 24-year-old agriculture student from Ghana, lived in Brazil for several years before deciding to head for the United States.

"I'm looking for greener pastures. A better life. I've been told the road isn't easy," said Abdu, who spent two weeks traveling from Brazil to Colombia by bus.

Ahead along the terracotta-colored trail carved through dense tropical rainforest is Augusto from Angola, who lived in Brazil for seven years doing back-breaking work for little pay.

"In Brazil they exploit you. As a welder, I only earned $200 to $250 a month," said the 25-year-old.

Saving for four years, he scrapped together about $3,000 for the journey to the United States, of which he had already spent $800 on bus fares and hostels before setting off on the Darién trek from seaside towns in Colombia's northern Urabá region.

Cashing in

For the tourist towns of Necoclí and Capurganá that are the gateway to the Darién Gap, a local economy replacing Colombian pesos with U.S. dollars has flourished to cater to the hundreds of migrants who pass through every day.

"We used to have to wait for the tourist season. Now we don't have to as there are migrants all year round ... migration will never end," said hostel owner German Julio.

It is a multi-million-dollar business and an increasingly lucrative sideline for the notorious Gulf Clan, Colombia's largest and most powerful drug cartel, local people said, though most were reluctant to discuss the details out of fear.

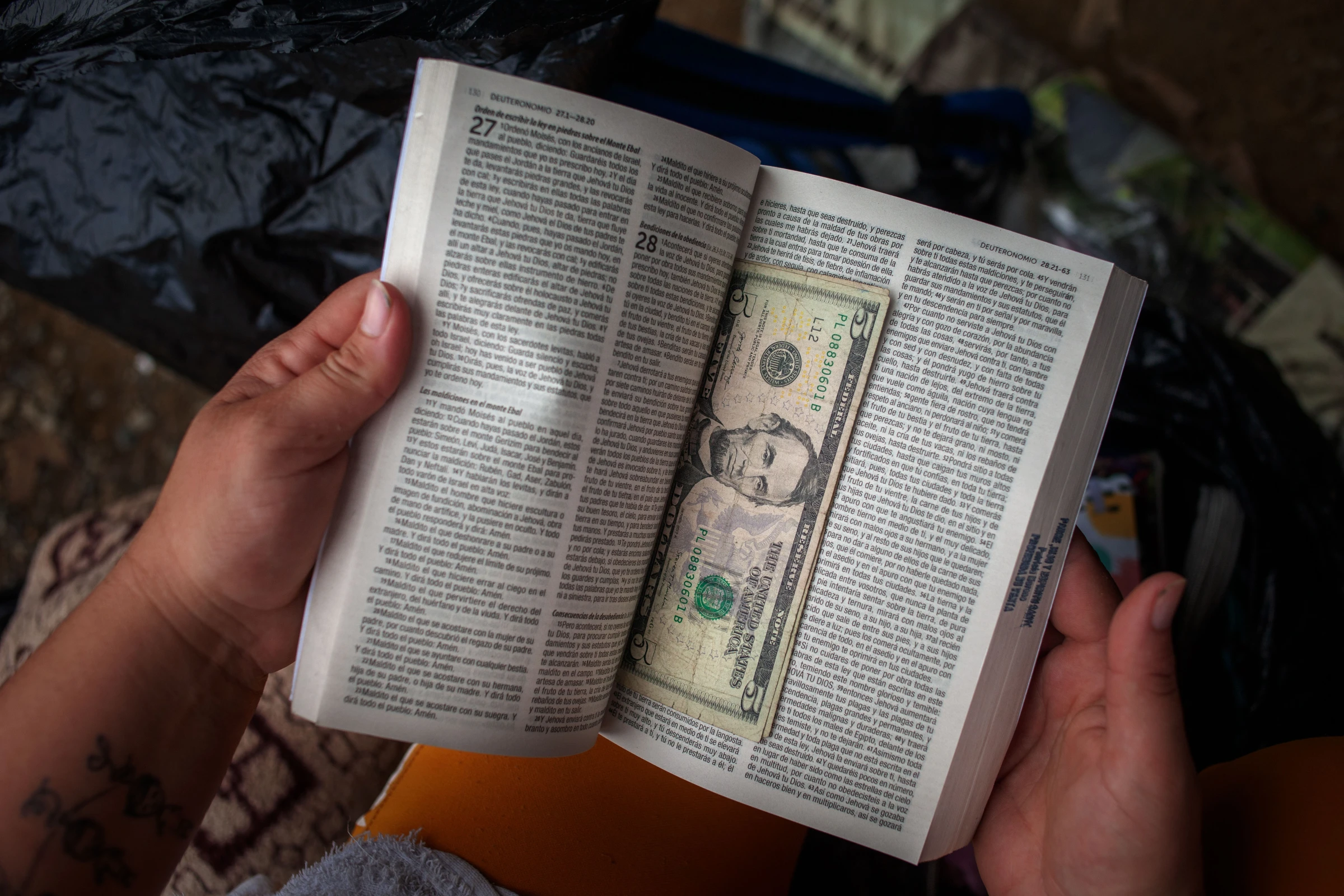

A Venezuelan migrant hides dollar bills in a bible carried in her backpack before negotiating a fee with jungle guides to take her and her family through the Darién Gap at a camping site in the Colombian town of Capurganá where migrants gather before setting off on the jungle trek. Migrants pay about $160 each to be led through the Darién Gap to reach Panama. Capurganá, Colombia, July 27, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

A Venezuelan migrant hides dollar bills in a bible carried in her backpack before negotiating a fee with jungle guides to take her and her family through the Darién Gap at a camping site in the Colombian town of Capurganá where migrants gather before setting off on the jungle trek. Migrants pay about $160 each to be led through the Darién Gap to reach Panama. Capurganá, Colombia, July 27, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Many migrants from Africa and Asia fly to Ecuador and Brazil where few visa restrictions allow an easy point of entry into the Americas.

But Venezuelans surpassed Cubans and Haitians as the largest national group making the crossing this year as new visa restrictions imposed by several Latin American countries make it harder for them to fly into Mexico and Central America. Some six million Venezuelans have fled their homeland since 2014.

Large numbers of them sought a better life in Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Chile, doing low-paid work as streets vendors, cleaners, washing car windscreens or laboring on building sites, but tens of thousands are on the move again.

With rising inflation and unemployment in Latin America and hopes that U.S. President Joe Biden will grant more Venezuelans Temporary Protected Status (TPS) or asylum, Venezuelans are heading north instead.

Wilbar, a 19-year-old Venezuelan migrant traveling with a group of Venezuelan families, at a camping site in the Colombian town of Capurganá, standing next to his backpack wrapped with plastic to protect it from the rain before starting the jungle trek through the Darién Gap. Capurganá, Colombia, July 27, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Wilbar, a 19-year-old Venezuelan migrant traveling with a group of Venezuelan families, at a camping site in the Colombian town of Capurganá, standing next to his backpack wrapped with plastic to protect it from the rain before starting the jungle trek through the Darién Gap. Capurganá, Colombia, July 27, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Wilbar, 19, who was traveling without a passport and had $90 stashed in his bible, left Venezuela when he was 15 and has been working on construction sites in Colombia since then.

To pay for the journey, he slept rough for several weeks to save on rent and camped on the beach in Necoclí where he earned $30 recycling plastic and cardboard for a few days.

"There are better opportunities in the United States. The possibility of a better life is there. My goal is to buy my mother and sister a house in Venezuela," said Wilbar, whose small backpack was wrapped in plastic to protect it from the humidity and frequent downpours in the forest.

"I hear there are jobs in New York. I will go where God guides me," he said.

Like many migrants, Wilbar has seen videos on TikTok of the treacherous journey showing migrants lying exhausted in the mud, or of children nearly swept away by the current of crocodile-infested rivers.

Moments earlier, a thin silver gray snake slithered over the muddy ground in front of him. Arnola - the Congolese boxer - swiftly slashed the snake in half with his machete, drawing cheers from a line of migrants behind him.

A former middleweight boxing champion who won national titles in his youth, the 34-year-old traveled from Brazil with his three nephews and nieces aged under 12 and his sister-in-law, the pregnant Angolan woman.

"My wife, who's in Angola, will sell our house and join me in the United States," he said, catching his breath as he rested on a rock.

Even for the relatively young and fit, the trek is an endurance test.

Less than an hour in, people weighed down by heavy loads and six-liter (1.3-gallon) water bottles were already struggling and needed frequent breaks.

Migrants from Venezuela and African countries take a break and bathe in a stream at the first camping site after a day of trekking in the Colombian jungle in the Darién Gap, Colombia, July 27, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Migrants from Venezuela and African countries take a break and bathe in a stream at the first camping site after a day of trekking in the Colombian jungle in the Darién Gap, Colombia, July 27, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Bags are made lighter. Clothes, shoes, and non-essential luggage are left behind, littering the forest with a trail of discarded belongings.

"How many more hills are left?," one Venezuelan migrant asks. His friend, who set off in beach sandals, walks barefoot in the slippery sludge.

"We haven't even started. The first day is the easy bit," a guide replies.

Among a group of young men from Nepal, is Rahul, 20, who is traveling with his older brother.

Sons of poor rice and goat farmers near Kathmandu, their voyage began two months ago leaving Nepal's capital by plane to reach New Delhi, then Madrid, and Sao Paulo from where they took buses to Colombia.

"It's a big journey," said Rahul, adding he aims to join his other brothers who are already living in New York. "It's hard to live in Nepal. Everybody wants to live in the USA."

Business hub

Moving migrants along the Darién Gap is a highly organized and slick business operation turning over hundreds of thousands of dollars a week and involving both Colombians and indigenous leaders in neighboring Panama.

In Necoclí, migrants have overtaken tourists as the main driver of the local economy.

Jungle guides and porters, boat companies, owners of hostels, restaurants and pharmacies, along with street vendors and money changers are all cashing in, often trading in dollars.

For street vendor Graciela Leon, 63, who runs a camping gear stall along Necoclí's beach boardwalk, the thriving trade that has sprung up around migrants has transformed her fortunes.

Street seller Graciela Leon sits next to her stall selling jungle kit to migrants in the Colombian beach town of Necoclí along the main beachfront promenade. About 750 migrants on average a day passed through Necoclí this year. Necoclí, Colombia, July 29, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Street seller Graciela Leon sits next to her stall selling jungle kit to migrants in the Colombian beach town of Necoclí along the main beachfront promenade. About 750 migrants on average a day passed through Necoclí this year. Necoclí, Colombia, July 29, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

"Before I was a housewife and didn't have a job," said Leon, who sells jungle kit including machetes, tents, rubber boots and snake repellent to migrants. She earns up to $70 on a good day.

Drugs also transit the area. The Urabá region is a major cocaine trafficking route, largely run by the Gulf Clan, which controls who enters the Darién Gap and takes a cut on the earnings of most local businesses, including those serving the migrants.

"A share does go to the illegal groups," said Wilfredo Menco, head of Necoclí's Ombudsman's Office, a government human rights agency.

Asking not to be identified for fear of reprisals, several people said the cartel charged a 20% protection tax, known locally as a "vacuna" or vaccine.

"Not a leaf moves without their permission," said one aid worker who did not want to be named.

Migrants from Nepal try on rubber boots and buy jungle kit to prepare for the jungle trek through the Darién Gap in the Colombian beach town of Necoclí. Necoclí, Colombia, July 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Migrants from Nepal try on rubber boots and buy jungle kit to prepare for the jungle trek through the Darién Gap in the Colombian beach town of Necoclí. Necoclí, Colombia, July 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

With some 1,200 combatants, the Gulf Clan is Colombia's largest organized crime gang and exerts territorial control over lawless parts of the Urabá region, where the military captured its leader Dairo Antonio Úsuga, alias Otoniel, last October.

But state authorities are largely absent in the area and tend to allow migrants to pass through towards the Darién Gap. There were no police or migration check points in Necoclí or Capurganá.

According to the human rights official Menco, 750 migrants on average a day passed through Necoclí this year, many spending a night or two in hostels charging them $7 per person per night.

Penniless migrants mostly from Venezuela who cannot afford a room sleep in the street or pitch tents on the beach under palm trees in between fishing boats and beach bars selling beer and shrimp cocktails.

Some Venezuelan families build sand castles and swim in the Caribbean sea while they wait for relatives in the United States to send money so they can continue their journey.

Douglas, a 31-year-old Venezuelan migrant traveling alone, poses for a photo on the beach in the Colombian town of Necocli before boarding a boat to Capurgana from where the jungle trek across the Darién Gap begins. Necocli, Colombia, July 29, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Douglas, a 31-year-old Venezuelan migrant traveling alone, poses for a photo on the beach in the Colombian town of Necocli before boarding a boat to Capurgana from where the jungle trek across the Darién Gap begins. Necocli, Colombia, July 29, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Douglas, 31, a Venezuelan father-of-three sold a speaker and a watch to afford food and hitchhiked part of the way from Peru where he worked as a painter and ice-cream seller.

He hopes to join family already living in Florida and send money home to help his son pursue a career as a baseball player.

"My American dream is to help my family so that my sons can fulfill their dreams. The U.S. would give me stability," he said.

'Hooded attackers'

From Necoclí, migrants wearing life jackets wait in orderly lines to board the same comfortable boats used by tourists to cross the Gulf of Urabá. They pay $40 for a two-hour ride to reach Capurganá, from where the jungle trek begins.

Here, they hand over about $160 each to be led through the jungle by organized teams of "guides" as the local people smugglers call themselves.

Migrants from Venezuela, Haiti, and parts of Africa and Asia walk along the pier in Necoclí to board a tourist boat to cross the Gulf of Urabá to reach Capurganá from where the jungle trek begins. Necoclí, Colombia, July 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Migrants from Venezuela, Haiti, and parts of Africa and Asia walk along the pier in Necoclí to board a tourist boat to cross the Gulf of Urabá to reach Capurganá from where the jungle trek begins. Necoclí, Colombia, July 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Based on a conservative estimate of 400 migrants crossing the Darién Gap daily, the guide business here is worth $64,000 a day.

Further along the route in Mexico, most migrants will end up paying another set of smuggler or "coyote" fees of up $15,000 to enter the United States illegally by crossing scorching desert and rivers to reach the southern U.S.-Mexican border.

In Capurganá, where the jungle trek begins, elected community leader, Carlos Alberto Ballesteros, is in charge of 30 guides, who each lead groups of about 25 migrants.

He was at pains to highlight that migrants are not abused, dumped or harmed along the Darién.

"We want it to be recognized that we take care of migrants and that this isn't human trafficking," he said, adding migration has created about 200 local jobs from boat ticket sellers to motorcycle taxi drivers.

Wearing life jackets, migrants from Venezuela, Haiti, and parts of Africa and Asia board a tourist boat in Necoclí to cross the Gulf of Urabá to reach Capurganá from where the jungle trek begins. Migrants pay $40 for a two-hour ride. Necoclí, Colombia, July 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Wearing life jackets, migrants from Venezuela, Haiti, and parts of Africa and Asia board a tourist boat in Necoclí to cross the Gulf of Urabá to reach Capurganá from where the jungle trek begins. Migrants pay $40 for a two-hour ride. Necoclí, Colombia, July 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Once they reach the border, the Colombian guides hand off the migrants to indigenous communities in Panama, who receive $10 from Ballesteros for each migrant who passes through their territory.

The Colombian porter who offered to carry the pregnant woman's bag said he had spent nearly two years in a Panamanian jail for working in the migrant business before being freed in July after prosecutors failed to provide evidence at his trial.

"I say I provide a service. I just carry bags if people want me to. Others say this is (illegal)," he said, asking not to be named. He added that he can earn between $150 and $200 during a trip.

Yet the United Nations and aid groups warn that many migrants experience extreme violence at the hands of armed bandits along the Darién crossing.

Migrants from Venezuela and African countries traverse dense jungle through the Darién Gap where people have died along the way and been targeted by attackers, according to aid groups. Darién Gap, Colombia July 27, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Migrants from Venezuela and African countries traverse dense jungle through the Darién Gap where people have died along the way and been targeted by attackers, according to aid groups. Darién Gap, Colombia July 27, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Medical charity Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), which runs two migrant reception centers in Panama, said 81% of its patients seen from April 2021 to June 2022 had witnessed and or were victims of some type of violence along the journey.

During that period, MSF dealt with 456 sexual violence cases, including mass rapes involving groups of 10 to 15 men, said Marisol Quiceno, head of MSF's humanitarian affairs.

Assailants, including "hooded attackers with guns" are known to check if women are hiding dollar bills in their vaginas, which is "another form of sexual violence," she said.

"Migrants have told us they have seen people being killed along the way. They have had their money stolen, and even food, medicine and boots taken away," said Quiceno.

'We want it to be safe'

Ballesteros, the leader of the guides in Capurganá, acknowledged that migrants have died in the jungle but said the deaths were due to injury, illness or heart attacks rather than violence.

"Migrants are treated well. We want the journey to be safe for migrants," said Ballesteros, as he handed out dollar bills totaling $5,000 to several Panamanian indigenous leaders drinking beers on the tiled porch of his upmarket house.

Colombian Carlos Alberto Ballesteros, an elected community and guide leader, hands out dollar bills to several Panamanian indigenous leaders on the porch of his home in the Colombian town of Capurganá. Indigenous leaders receive a share of guide fees for each migrant who passes through their territory. Capurganá, Colombia, July 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Colombian Carlos Alberto Ballesteros, an elected community and guide leader, hands out dollar bills to several Panamanian indigenous leaders on the porch of his home in the Colombian town of Capurganá. Indigenous leaders receive a share of guide fees for each migrant who passes through their territory. Capurganá, Colombia, July 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Indigenous leader Juan Martinez from Panama's Kuna rainforest tribe said his community helps migrants in need.

In July, a sick migrant arrived at his village barely able to stand and covered in mud.

"He had diarrhea and was vomiting. He was dying. We helped him to get better," said Martinez.

A new and easier route through the Darién lasting up to seven days started in November 2021, replacing a longer and more dangerous one that used to take nine, Ballesteros said.

Earlier this year, he built a shaded campsite in Capurganá where migrants can pitch tents, and access clean toilets and cellphone charging points before setting off. Several other campsites with tarp roofs exist along the route.

Back on the trail as dusk approached, at the first campsite, dozens of weary migrants pitched tents and lit camping stoves to cook while children splashed in a nearby river and others washed the mud from their arms, feet and legs.

"People say 'how can you do this with children?'. But it's more painful to leave our children behind in Venezuela. I told my daughter we're going to see Mickey Mouse's house," said Macyuli, a migrant traveling with her four children and husband.

Venezuelan migrant Macyuli, traveling with her four children and husband, and other Venezuelan families, walks along the jungle path through the Darién Gap carrying her daughter. Darién Gap, Colombia, July 27, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Venezuelan migrant Macyuli, traveling with her four children and husband, and other Venezuelan families, walks along the jungle path through the Darién Gap carrying her daughter. Darién Gap, Colombia, July 27, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

When they make it through the wall of jungle, migrants still face a journey of roughly 2,500 miles (4,000 km) and five borders through Central America before they reach the toughest barrier of all - the U.S.-Mexico border.

"We go with the hand of God. The lord is our guide," Macyuli said, resting on the riverbank.

New to Context? We'd love for you to find out a little more about what we do. Click here for a selection of our best work.

Reporter: Anastasia Moloney

Editor: Helen Popper

Photographer: Fabio Cuttica

Graphics: Tom Finn

Producer: Amber Milne

Tags

- Unemployment

- Wealth inequality

- Poverty

- Migration

- Economic inclusion

- Underground economies