Q&A: Palau pledges cleanup of abuse-riddled ship-flagging system

President of Palau Surangel Whipps Jr. at the Buergenstock Resort in Stansstad near Lucerne, Switzerland, June 15, 2024. REUTERS/Denis Balibouse

What’s the context?

President Surangel Whipps speaks with Context about the challenges Palau faces in regulating ships that sail under its flag.

NICE, France - The leader of the island nation of Palau, whose ship registration system has come under fire for allowing rogue companies to fly its flag, has pledged to improve oversight of vessels to comply with international regulations.

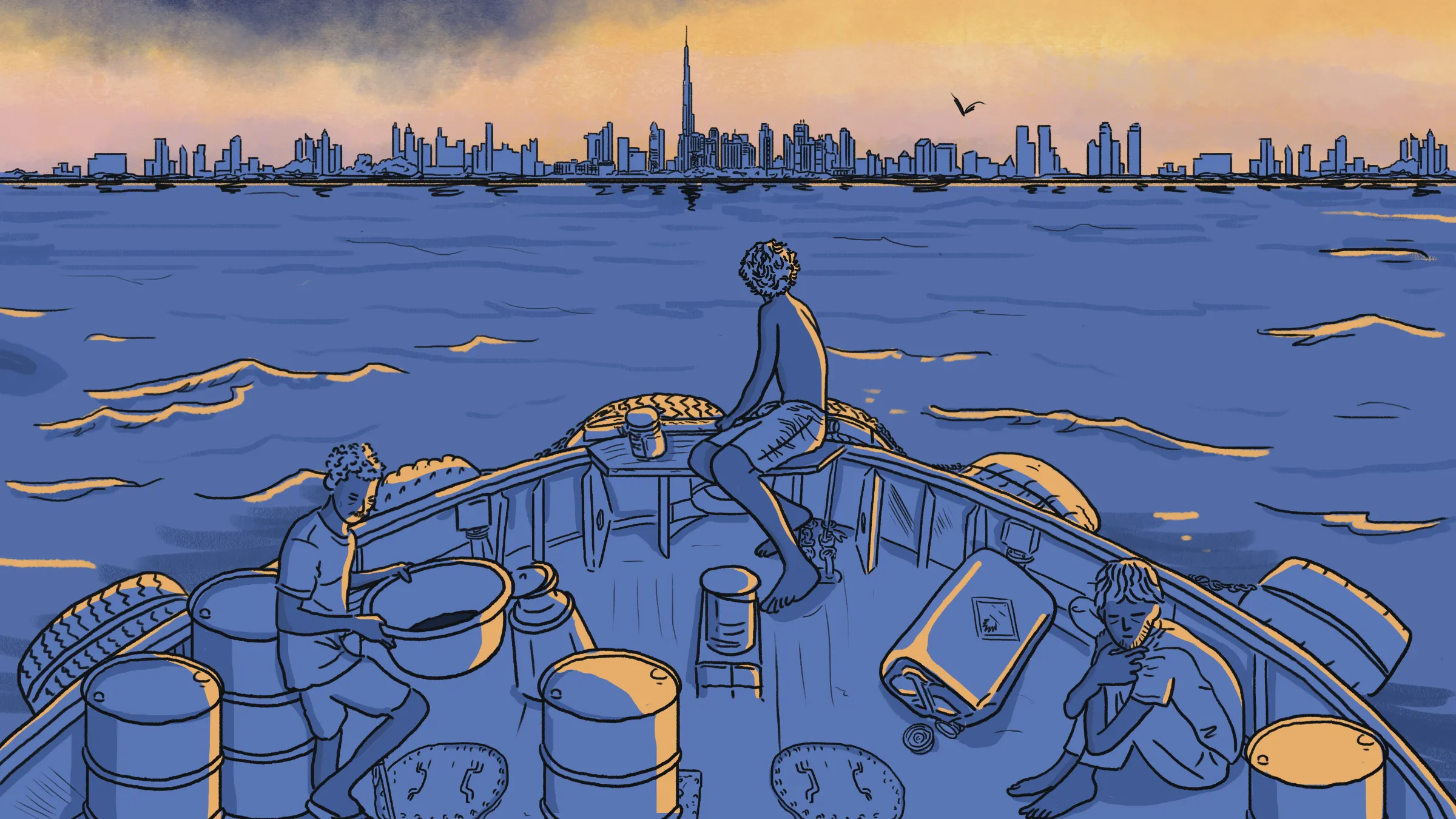

Palau is grappling with gaps in monitoring and enforcement, particularly around vessel abandonments and "dark fleet" operations, President Surangel Whipps told Context on the sidelines of the U.N. Ocean Conference in Nice, France, in June.

"We need to up our game," he said. "We need to be more diligent in checking and making sure that we don't have some (substandard) vessels registered."

Palau ranked among the four worst flag states for its registered ships' treatment of seafarers in 2023, according to the International Transport Workers' Federation (ITF).

Last year, Palau-flagged vessels accounted for the world’s second-highest number of ship abandonments, in which owners simply walked away from ships and crews, the ITF said.

"I didn't know about the issue" of ship abandonments, Whipps said. "We’ve got to clean that up. That's not good."

Palau operates an open registry, allowing foreign-owned ships to fly its flag, regardless of whether owners have any economic ties to the country.

Such flags of convenience are magnets for shipowners looking to skirt labour and safety standards, according to shipping experts.

International maritime organisations argue that the flag of convenience system undermines safety and labour standards by letting shipowners register vessels in countries with weak oversight and little enforcement.

However, registration fees can be a significant source of revenue for nations with smaller economies. Palau, whose economy is worth about $320 million, does not publicly disclose its earnings from the registry.

The International Maritime Organization has warned that countries operating such registries must still adequately control ships flying their flag, in line with Article 94 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Whipps acknowledged Palau has difficulties in verifying that the vessels carrying its flag are not engaged in illicit activity, citing a lack of resources and capabilities.

"We try to be on top of it. But it's a thousand vessels that are currently registered. We've got to do a better job," he said.

Figures from the U.N. Trade and Development agency showed 433 ships flew Palau's flag in 2023, out of an estimated global merchant fleet of 109,000 vessels.

The Paris Memorandum of Understanding, an international agreement that established a system of port inspections for foreign ships in participating countries, blacklisted the Palau flag in 2017, denoting poor safety and labour records.

Being blacklisted leads to more frequent inspections, higher detention rates and reduced trust in vessels flying the flag of that state.

Since July 2017, 67 ships flying Palau's flag have been reported abandoned by owners who have decided it is cheaper to ditch their vessel than to operate them, according to International Labour Organization data.

One of those was the Ula bulk carrier, abandoned off the coast of Iran after the ship's owner stopped paying wages and supplying food, water and fuel in 2019. The crew was stranded for more than 2-1/2 years.

The ITF criticised Palau for not providing assistance to the crew, and the government responded by delisting the Ula from its registry, effectively absolving itself of responsibilities to the crew.

Palau, which straddles more than 500 islands in the Pacific Ocean and has a population of fewer than 20,000 people, requires support from other countries to verify the vessels it registers due to a lack of expertise, Whipps said.

"It's tough,” said Whipps. "We've got to do everything. We've got to rely on intelligence, we've got to rely on other people sharing information, so we can make informed decisions."

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Ocean Reporting Network.

(Reporting by Katie McQue; Editing by Ayla Jean Yackley.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles