The Haida fought logging in Canada. Now they control its future

What’s the context?

Guardians of ancient Canadian cedars are divided over the future of logging on their windswept island outpost

On a string of wild and rocky islands off northwestern Canada, the Haida people revere the cedars that tower overhead as a nurturing older sister.

For millennia, the trees have given the Indigenous Haida timber to build beamed longhouses, blankets to weather winter, canoes to wend the waterways and shoes to shod their feet.

In the archipelago's rare, temperate rainforests - some of which are thought to pre-date the last ice age - mammoth red cedars dapple the damp undergrowth far below, land that is rich with huckleberry and ferns and carpeted in luminous moss.

But since the logging industry took hold a century ago, little of this pristine landscape is left.

Few old-growth cedars remain either.

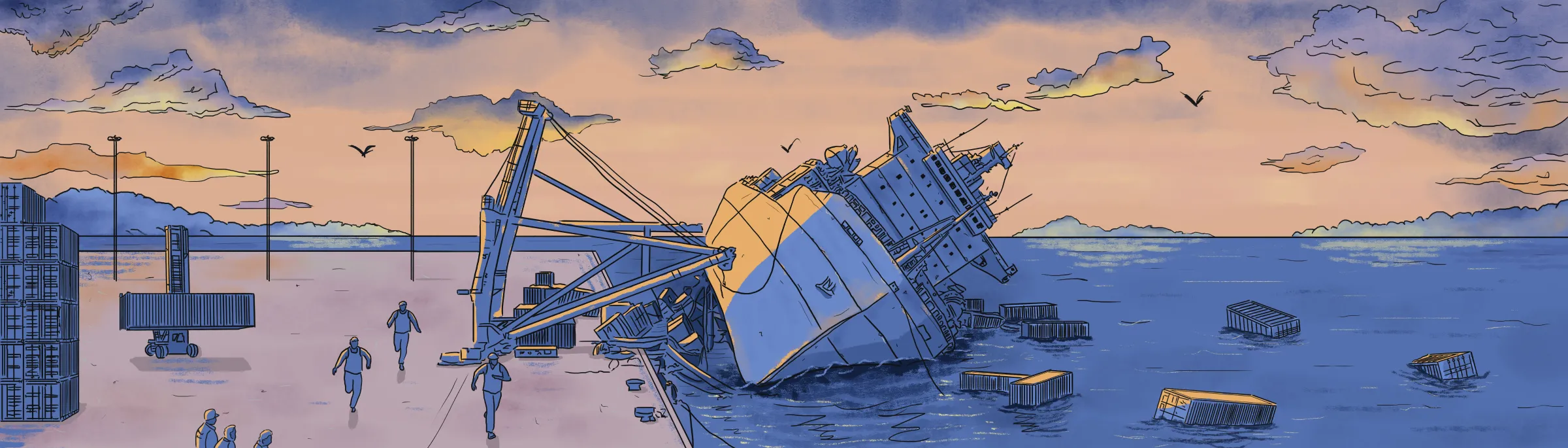

Locals have watched for decades as huge barges, brim-full with outsized logs, set sail from the windswept Pacific shore and head for the mainland 100 km (62 miles) away.

"Most people feel a sick feeling in the pit of their stomach when they see barges full of trees leaving the islands," said Gwaai Edenshaw, a traditional carver in Masset, a village in the north of the Haida Gwaii archipelago.

A logging truck transports second-growth sitka spruce logs for Haida-owned company Taan Forest, on Graham Island, Canada. July 24, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

A logging truck transports second-growth sitka spruce logs for Haida-owned company Taan Forest, on Graham Island, Canada. July 24, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

Armed with new powers over the forests, the Haida Nation has a dilemma of its own: to log or not to log.

"That's what we're having to face as a nation, you know, just this big question of who we are and what is necessary for us to exist as a nation," Edenshaw said.

Alongside his brother Jaalen, Edenshaw chiselled notches in a felled cedar to carve a traditional totem pole in honor of their father, Guujaaw, chief of the ancient village of Skedans.

The totem pole will be raised at a potlatch in October.

For now, though, the prostrate cedar fills their roomy workshop, a giant laid amongst tools and wood shavings, the air fragrant with cedar chips.

The precious wood was once used just by the Haida and in modest numbers only, meeting the daily needs and customs of an estimated 20,000 people.

In the late 19th century, diseases brought by European settlers cut the Haida population to less than 600.

Since then, industrial logging has cut 110 million cubic metres of old growth trees, each one about the size of a telegraph pole, according to 2023 analysis by the Gowgaia Institute, a non-profit on Haida Gwaii.

That's worth 16 billion Canadian dollars ($11.8 billion) in today's money, according to the data shared with Context, most of which went to people outside Haida Gwaii.

When logging peaked in the 1980s, the Haida staged a series of protests against the industry, from roadblocks to lawsuits, wresting more control over their land in the mid-2000s.

In May, the Haida people - who make up half the island's 4,500-strong population - won recognition of their land title over the islands from British Columbia, the first agreement of its kind to take place in Canada outside the courts.

"It's our island, it's our job to take care of, and that doesn't mean no logging or no development. It just means we're the ones who are charged with taking care of it, " said Tyler Hugh Bellis, a forestry advisor to the Council of the Haida Nation.

"Obviously, we've been shown other people can't do that."

Old growth

A centuries-old red cedar tree stands tall in the temperate rainforest of Haida Gwaii on Graham Island, Canada. July 25, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

A centuries-old red cedar tree stands tall in the temperate rainforest of Haida Gwaii on Graham Island, Canada. July 25, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

Old-growth forests - trees that are at least 250 years old - are crucial to absorb planet-heating carbon dioxide, and store far more carbon than equivalent younger forests.

The rainforests also protect vital biodiversity, including more than 6,800 species of plants and animals with sub-species unique to the islands, such as the Haida Gwaii black bear.

The Haida hope the title will give them greater control over their future, allowing them to run the forests as one unit, instead of having different firms hold licenses.

"Always before it was industry pushing, and us putting up rules to make sure to save our culture," Bellis said. "If it's all one collective, the sky's the limit."

Taan Forest workers show markings for protected trees in the temperate rainforest of Haida Gwaii on Graham Island, Canada. July 24, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

Taan Forest workers show markings for protected trees in the temperate rainforest of Haida Gwaii on Graham Island, Canada. July 24, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

Now, most logging is done by Taan Forest, a company founded in 2010 and owned by the Council of the Haida Nation.

Ever since, logging has been reduced under a land-use plan agreed between the council and British Columbia, with some protections for culturally-significant trees and biodiversity.

But there is intense debate on the islands about whether Haida people should be logging at all.

"We put so much of our identity into the battle and fighting against logging," said Edenshaw.

"It kind of created a division in our souls."

Sustainable logging?

Walking through densely-packed forests on Graham Island, the largest of the more than 200 islands, engineers from Taan Forest show which trees they've marked to protect them from felling.

These include "monumental" trees, big and of high enough quality to make totem poles or canoes, and trees already altered by Haida - such as those shorn of bark - in line with tradition.

A "monumental” tree – big and of high enough quality for traditional uses like totem poles or canoes – f is marked out for protection in Haida Gwaii, on Graham Island, Canada. July 24, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

A "monumental” tree – big and of high enough quality for traditional uses like totem poles or canoes – f is marked out for protection in Haida Gwaii, on Graham Island, Canada. July 24, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

Guy Lawson, who has been working with Taan Forest for 12 years, pointed to the buffer set around trees they cannot log, along with natural features like rivers and plants ringfenced for traditional medicines such as "devil's club" and crab apple.

"The way we're doing it now is a lot better than logging of the past," said Lawson, one of eight full-time Haida employees at Taan, which has 18 full-time staff and whose 46 contractors have a combined 236 employees.

"We're looking at the future and trying to change things. My uncle was a faller for years, and I can't blame him for what he did," he said.

Guy Lawson, working with Taan Forest for 12 years, identifies trees and other natural features like rivers they cannot log, on Haida Gwaii, on Graham Island, Canada. July 24, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

Guy Lawson, working with Taan Forest for 12 years, identifies trees and other natural features like rivers they cannot log, on Haida Gwaii, on Graham Island, Canada. July 24, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

An annual harvest limit is mandated under the land-use agreement, seeking to improve the health of natural ecosystems.

Taan can fell up to about 420,000 cubic metres a year, but the firm usually only cuts about half of its allowance, said Chief Forester Jeff Mosher.

The company is one of just three in British Columbia certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), widely seen as the strictest global forestry sustainability standards.

Among the benchmarks it judges, the FSC rates firms for community engagement, protection of at-risk species and landscape preservation for the good of connected ecosystems.

"I'm very confident that we have a very sustainable harvest rate where it's set right now, but there is a real strong push from the public, from the Haida Nation, to see that rate be reduced even more," Mosher said.

Even with such protections in mind, swathes of trees are lost in one fell swoop, with up to 40 hectares (100 acres) felled in a block.

Left behind is a grey wasteland that stands in ugly contrast to the vibrant greens and browns that grew before.

Taan is increasingly felling second-growth trees, which grew after older forests were felled decades ago, but old growth still makes up about half of its haul.

Rachel Holt, an independent ecologist in British Columbia for 30 years, said second-growth forests cannot replace the lost biodiversity and carbon.

"These forests are never ever coming back. They are ancient. They have value beyond anything anybody can imagine. And we continue to decimate them to make a bit of money," she said.

Taan Forest old-growth red cedar logs set aside for cultural purposes like totem poles and canoes in Haida Gwaii, on Graham Island, Canada. July 23, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

Taan Forest old-growth red cedar logs set aside for cultural purposes like totem poles and canoes in Haida Gwaii, on Graham Island, Canada. July 23, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

They are home to boundless biodiversity, and a carbon density to rival any forest in the world, Holt explained. Most of this is released into the atmosphere when they are logged.

Although half the island is protected, the richest ancient forests tend to be in areas where forestry is active.

Holt said felling was not inherently an evil, so long as at-risk forests are protected and local communities benefit.

"They do a better job on Haida Gwaii than in other places," she said. "But the question is, should you be doing it at all?"

Finding balance

Without felling ancient trees, the business as stands would not be viable, said Mosher, though Taan wants to change that.

Logging is a declining industry in western Canada, and new eco-standards only increase production costs.

About 9% of the islands' ancient forests can legitimately be cut, since 68% have been felled already and 22% sit in a protected area, according to the Gowgaia Institute.

For forest advocate Lisa White, a long-time campaigner on the islands, this calls for a complete rethink.

"I've heard people say a number of times that we've got to balance the environment with the economy. And to me I say 'we're really out of balance. They've been taking from our land for 100 years'," said White.

The current land-use plan is not strict enough "and it's not working, in my opinion," she said.

Instead she urged a switch in focus to nature restoration and ecotourism, restricting any logging to local use.

"Because people come here, they want to see nature. They don't want to see stumps," she said.

The stump of a tree covered in mosses on the Golden Spruce trail in Haida Gwaii, on Graham Island, Canada. July 23, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

The stump of a tree covered in mosses on the Golden Spruce trail in Haida Gwaii, on Graham Island, Canada. July 23, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

One of the frustrations for White and other Haida people is the lack of direct community benefits from logging.

Historically, pools and skating rinks used to be enjoyed in camps of off-island loggers, but the swimming pool in Masset closed years ago.

Taan Forest's council-owned parent company, Haida Enterprise Corporation (HaiCo), previously used forestry profits to invest in its ecotourism and fishing firms, and first distributed cash to the council in 2022, Mosher said.

However he pointed to other benefits - the jobs created, the roads and bridges maintained, along with extra community wood for heating, building and cultural uses.

The company is also seeking funding under carbon credit schemes to restore areas that were previously logged, with the hope of reviving more acres of forest than it cuts.

Brodie Swanson, Deputy Chief of Old Massett Village Council, said such work will eventually replace traditional logging.

"It's my firm belief that there's going to be a shift in the way forestry is looked at on Haida Gwaii as far as remediation and bringing forest back," Swanson said.

He explained second-growth forests are often barren compared to old growth, as little sunlight ever reaches the undergrowth.

"That's the great thing about old growth. It allows light in and different age trees all over the place. It's more hospitable to (the) ecosystem," Swanson said.

A new direction

With the land title secured, the community has a two-year transition period to create a new plan for forestry.

Garry Merkel, a forestry advisor and expert on old-growth forests, said the title gives the Haida a veto power rather than full jurisdiction.

This could lead to a new direction that "more accurately reflects the Haida view of the world and how you properly steward the land," he said.

It also means pushing for more value-added industries on the island, creating mills and other local enterprises rather than sending unprocessed logs to the international market.

Merkel said it would be hard to enact such a shift due to government policy and market forces that encourage high volumes of timber being sold as a commodity.

"This province was built on the backs of timber," he said.

In 2022, forestry provided 1.9 billion Canadian dollars ($1.4 billion) in provincial government revenues, and added 6.4 billion Canadian dollars ($4.7 billion) to the province's GDP.

But little of that value has been seen locally.

Standing on the dock in Skidegate, a village in the south of Graham Island, tree planter Glynn MacLeod hopes the land title may change that.

"They all made money. Now, where's our rec(reation) centre? Where's our swimming pool?" said MacLeod, who has been planting trees for forestry companies for 25 years.

He thinks companies should be made to hire locals, and wants the provincial government to introduce higher charges on firms for wasting wood so they use all the wood they cut down.

"Let's just scale it way down, produce the final product, employ everyone and not have to harvest so much," he said.

Up in Masset, Gwaai Edenshaw also sees new options - and says it might eventually make more economic sense to protect the forests than fell them.

"The question is, do we need to log to have money?" he said.

Working on his father's totem pole, Edenshaw explains why these ancient cedars are perfect for the job at hand.

An eagle flies past a totem pole carved by Haida carver Christian White in Old Massett, in the north of Haida Gwaii on Graham Island, Canada. July 23, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

An eagle flies past a totem pole carved by Haida carver Christian White in Old Massett, in the north of Haida Gwaii on Graham Island, Canada. July 23, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham

The wood, he says, responds predictably to tools, and its natural oils protect it from insects and fungi.

"So it can stand outside in the weather for a long time," he said. "Long as any of us will be around anyway."

The Forest Stewardship Council covered travel expenses for this story.

Reporting: Jack Graham

Editing: Lyndsay Griffiths

Photography: Jack Graham

Production: Amber Milne