Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Context or the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Iran's water crisis is driven by bad policies, but tech can help

The Jajrood River that runs to the Latian Dam is dried up as Iran faces extreme drought, Lavasan, Iran, March 18, 2025. Middle East Images/handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Decades of poor decisions have turned a challenge into a disaster, but new tech and bold action could ease Iran’s water crisis.

Nima Shokri is the Chair and Director of the Institute of Geo-Hydroinformatics at the Hamburg University of Technology (TUHH) in Germany and the Executive Co-Director of the United Nations University Hub on Engineering to Face Climate Change at TUHH.

Imagine living in Tehran, a bustling city of around 10 million people, where the taps run dry for hours each day. Reservoirs that supply the capital of Iran are only 21% full, a historically low level, according to local media reports.

On August 11, Mohsen Dehnavi, spokesperson for the Expediency Discernment Council, a constitutional advisory body for Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, warned that “day zero” could be reached in a few weeks, meaning the city’s drinking water reserves would be exhausted.

Across Iran, millions of people face severe water shortages. This is not just a crisis – it’s a catastrophe, threatening lives, livelihoods, and socio-economic stability.

Climate change is making things worse. Droughts and lack of rainfall drive higher evaporation rates and reduced inflows - water entering rivers, reservoirs, lakes, dams and aquifers.

The numbers tell a grim story.

Since the 2025 water year – a 12-month period used by experts to compare water data - began in October last year, rainfall levels have plummeted to 141.7 millimetres - down 39% from the long-term average of 230.6 millimetres, and 40% less than last year’s 238 millimetres, according to Iran’s water records and data.

Authorities in Iran often blame drought or overuse of water for shortages, but the evidence points clearly to mismanagement, including excessive dam construction, failure to crack down on illegal wells and the expansion of water-intensive farming and industry.

This is not solely because of climate change; it is a textbook case of human error and choices that favour quick gains over long-term survival.

If Iran doesn’t act to end this mismanagement, the consequences will extend beyond its borders and will include forced migration, conflict, poverty and famine.

Decades of poor decisions have turned a challenge into a national disaster. Iran’s groundwater, a lifeline in this arid land, is vanishing fast.

Iran’s state media says the number of agricultural wells has skyrocketed from 47,000 to over a million in 40 years, with nearly half operating without permits.

This has drained aquifers, with estimates of 145 - 350 billion cubic metres lost.

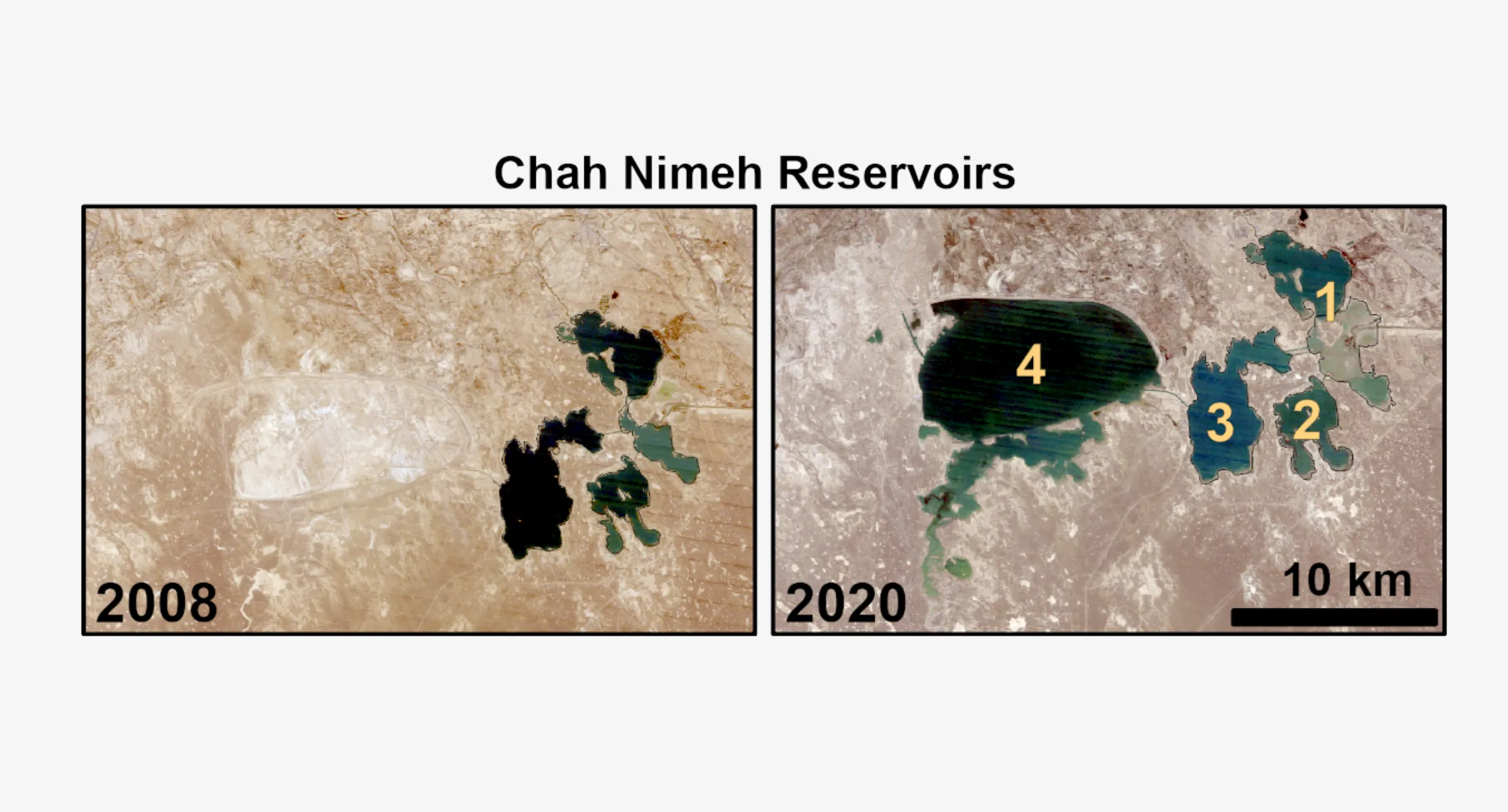

For example, in Chah Nimeh in the Sistan-Baluchestan province in southeastern Iran, near Afghanistan’s border, we found that four reservoirs could lose as much as 385 million cubic metres annually to evaporation, due to their large surface area, searing heat, and strong winds.

Landsat data showing Chah Nimeh reservoirs. Nima Shokri/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Landsat data showing Chah Nimeh reservoirs. Nima Shokri/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

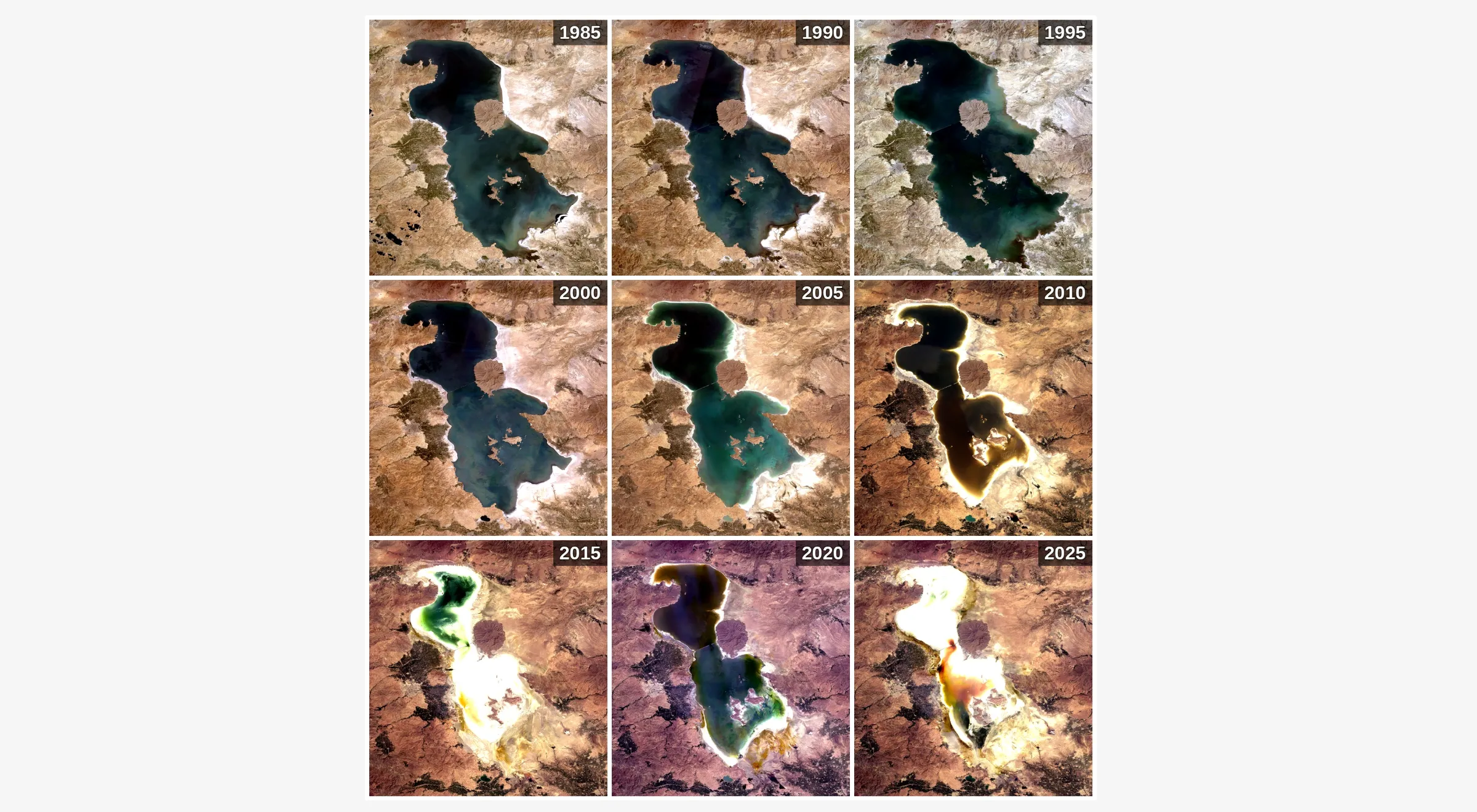

Or consider Lake Urmia, once the Middle East’s largest saltwater lake.

Its collapse is even more dire and there is a possibility that it could completely dry up by the end of summer 2025, according to the Department of Environment.

By August, water volumes had dropped to 500 million cubic metres from 2 billion last year.

A study published in the Nature journal last year, said 103 dams in the lake’s basin were choking off its water supply.

There are also around 48,000 illegal wells, according to the Agriculture Ministry, draining groundwater, and use of these wells has increased more than threefold since 1973.

Landsat data showing Lake Urmia over four decades. Nima Shokri/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Landsat data showing Lake Urmia over four decades. Nima Shokri/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

The fallout is heartbreaking. As Lake Urmia shrinks, dust storms from its exposed bed are choking nearby communities – a threat we predicted in 2020 when we modelled regions that would be affected if the lake dried up.

Farmers cultivating water-hungry crops, such as sugar beets, now also face ruin.

A path forward

Iran cannot undo decades of water mismanagement overnight, but technology offers a lifeline. Satellites can monitor reservoir levels and detect illegal wells in real time.

Artificial intelligence can predict droughts and optimise irrigation, cutting water waste in farming.

Big data - satellite imagery, hydrological sensors, and climate information - can pinpoint usage inefficiencies. Advanced analytics and AI models can then design tailored conservation strategies. These tools could save billions of cubic metres of water annually and guide sustainable policies.

Yet technology alone isn’t enough.

Iran’s water crisis, alongside frequent power cuts, heatwaves and economic pressures, risks sparking unrest and displacement.

The government must act boldly: seal illegal wells, halt excessive dam construction, price water realistically, scale up wastewater reuse and repair ageing infrastructure and water networks that lose water in transit.

Iran has the talent to embrace these solutions and the potential to forge international partnerships for access to cutting-edge tools and finance, which depends on pursuing sound foreign policy and international collaboration.

The skies may not cooperate, but human ingenuity can.

Tags

- Extreme weather

- Climate policy

- Tech solutions

- Water

Related

Latest on Context

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6