Net zero credibility: 5 learnings and 3 calls to action on 1.5°C-aligned transition plans

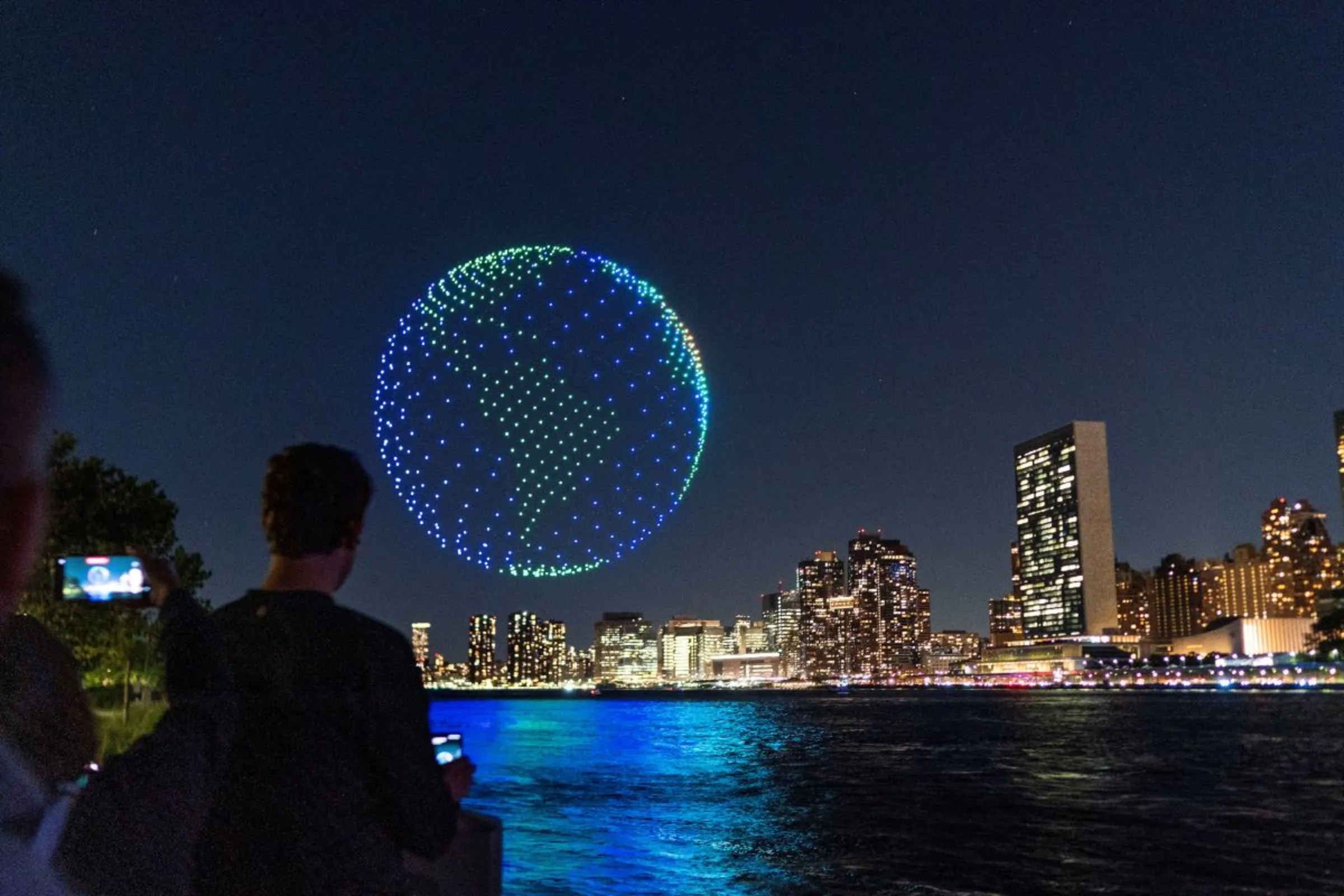

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres delivers a statement during the opening of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Summit 2023, at U.N. headquarters in New York City, New York, U.S., September 18, 2023. REUTERS/Mike Segar

With the Climate Ambition Summit, companies need to act now to align with a 1.5°C future

Claire Wigg is Head of Climate Performance Practice at the Exponential Roadmap Initiative. Johan Falk is CEO of the Exponential Roadmap Initiative

We got our marching orders from Antonio Guterres, the UN Secretary-General. He wanted to see company transition plans aligned with 1.5°C for his Climate Ambition Summit on September 20. The Exponential Roadmap Initiative team worked with more than ten companies to develop such plans. Here’s what we learned.

Learning 1: Transition plans use a new framing

Transition plans following the UN’s implementation checklist focus on phasing out fossil fuels from the value chain in addition to reducing emissions. This framing of net zero targets in terms of phasing out fossil fuels, as well as reducing greenhouse gas emissions, is new to many companies - and makes a difference.

For example, an emissions reductions target may be to reduce scope 2 emissions by purchasing renewable energy, or to aim for 100% of energy used by tier one suppliers to be renewable by a certain time. But a target for phasing out fossil fuels requires different language and targets.

The new framing also introduces a hierarchy of fossil fuels: number one, no coal, number two, no oil, number three, no gas. This means that companies need new ways of quantifying, measuring and reporting progress. They need to start seeing the fossil-based sources of the emissions they’re already seeking to reduce and identify where these are in the value chain, then set goals and take concrete action on these fossil fuels.

Learning 2: Transition plans are much more fundamental than copy-paste

The starting point for writing a company transition plan is often text from companies’ existing documents, for instance sustainability reports. But a good transition plan requires companies to produce new text covering points that existing documents do not address.

The transition plan also requires increased transparency about planned climate actions, particularly regarding scale: It matters whether a company plans to electrify 1,000 vehicles out of a 10,000-vehicle fleet, or out of a fleet of 100,000. Similarly, companies need to be more transparent about definitions and standards using certain key terms.

Learning 3: Transition plans are fundamentally about creating new business models

Transition plans ask whether a company’s business model is fit for purpose in a 1.5°C-world. Every company that operates today has to transition or in many cases to transform itself.

Only start-up companies that were set up with the 1.5°C-world in mind can skip this transformative process. These would for example be climate solutions companies that provide a product with a significantly lower carbon footprint than the business-as-usual solution being replaced, or that provide a service with the sole purpose of enabling others to avoid or reduce emissions.

Learning 4: How a company is owned and run matters to its transition options

If companies conceive of the transition plan as a transformation plan, it is beyond the usual scope of the sustainability officer’s work. Developing a transition plan requires addressing business strategy and formulating targets in a new and different way. That’s why a good transition plan may well require board-level decisions.

But, ownership, too, makes a difference because transition plans set the pathway for the next 10 to 20 years. That may be easier for companies in private or family ownership that tend to set strategy according to longer horizons than publicly-listed companies.

The transition options of a listed company could further be limited by majority owners’ views. That is especially true for the energy sector and other industries that are strategically important for governments. In many countries, governments hold a significant share in energy and other key infrastructure companies and companies’ transition plans may well be constrained by governments’ security interests.

Learning 5: Different sectors have different sticking points in the transition - but energy is always one

For energy companies, the transition is obviously all about energy. But for any telecoms or IT company, the transition is also all about renewable energy. For manufacturing, too, it’s about renewable energy - as well as materials.

Based on these learnings, here are three calls to action.

The first is to CEOs and Boards: CEOs and boards need to realise that the time to start transforming their businesses is now to align with a 1.5°C future. They need to start figuring out what the company’s business model can be in a net-zero world.

The second is to world leaders: Governments need to phase out fossil fuels from their grids and transport to stay attractive for companies. That’s particularly important in the global manufacturing strongholds that manufacture most of the textiles, electronics, cars and machinery consumed around the globe. But governments here need the support from those countries where large corporations are headquartered.

The third call to action is to the UN system: The UN should be creating fora in which leaders in government, financial authorities and financial institutions listen to the needs of businesses that are in the frontline: businesses that have credible transition plans in place, are ready to lead the transformation - but need enabling policies, regulations and financing.

Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Context or the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Tags

- ESG

- Finance

- Adaptation

- Net-zero

- Corporate responsibility

Go Deeper

Related

Latest on Context

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6