Unprotected by laws, US workers pay the cost of record summer heat

What’s the context?

Workers deal with physical, psychological and economic consequences working in states with no regulations to protect them from extreme heat

Filiberto Lares spends his days in a truck with no air conditioning restocking airplanes with food and drinks at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport, where temperatures inside his cab can reach 120 degrees Fahrenheit (49 degrees Celsius).

Lares struggles to protect his soles from the scorching metal in the trucks, but is still often left with a painful burning sensation in his feet.

"I try to do my eight hours, run away to my car, take my shoes away and put on some sandals for my feet to recover, because I cannot handle it anymore," said Lares.

"It is not easy to be working in these conditions," he said.

Indoor and outdoor workers across the United States have suffered in this year's record summer heat, in many cases in states without regulations guaranteeing access to shade, air conditioning, fresh drinking water, or even regular breaks.

The lack of legal protection damages not only people's physical and mental health, but also their often already-fragile personal finances. Critics say it is also bad for businesses.

To tackle the issue, President Joe Biden's administration is advancing a first-of-its-kind proposal to safeguard indoor and outdoor workers from extreme heat, but it could be years before the new rules take effect.

In the meantime, a handful of states have set their own heat protection rules. But others, like Texas and Florida, have blocked local authorities from introducing regulations, including even rules on access to water and rest breaks.

"It is common sense that people working under the heat need water, breaks and shade. But when employers do not provide these simple measures, the cost is the worker's life," said Abigail Kerfoot, a lawyer with the Centre for Migrants' Rights, which has offices in Mexico and the United States.

Health risks

Kenia Rodriguez works in a warehouse making plastic goods in Houston, Texas. Four of her coworkers fainted in a single day because of the high temperatures, she said.

"I have been dehydrated, with dizziness, vomit and headaches. I have felt close to fainting, with my body dripping with cold sweat, but burning from the heat in the warehouse," Rodriguez said.

But as a mother of five children, Rodriguez needs to make a living and taking time off hurts her finances.

Other workers said they regularly experienced adverse physical and psychological symptoms from working in extreme temperatures.

If the human body remains at a high temperature for too long it can damage vital organs, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"It's not just heat stroke, you can have heat-induced cardiac arrest. The heat can combine with the issue of dehydration and cause kidney failure ... it can really sneak up on you," said Juley Fulcher with the advocacy group Public Citizen.

Worldwide, nearly 19,000 people die every year and 26.2 million people are living with chronic kidney diseases linked to workplace heat stress, according to the U.N.'s International Labour Organization.

In the United States, 986 workers died from exposure to heat between 1992 and 2022, with the construction industry accounting for 34% of all deaths, Bureau of Labor Statistics data show.

U.S. farmworkers are 35 times more likely to die from heat-related causes than other workers, studies have found.

A 2018 study by the Farmworker Association of Florida and the Emory School of Nursing found that 33% of farm workers had suffered acute kidney injury on at least one workday and 81% were dehydrated post-shift on a typical workday.

"Every week we receive complaints from workers saying that they're working under temperatures up to 40 degrees Celsius without any fans. It is inhumane and cruel," said Ernesto Ruíz, research coordinator at the Farmworker Association of Florida.

Cost and loss

Construction worker Elder Portillo has suffered headaches, fatigue and vomiting while working under temperatures of up to 95 F (35 C) in Newark, New Jersey.

"I feel my blood boiling, as if my skin was on fire. Even after taking a shower my body feels very tired and it is very difficult to wake up the next day," said Portillo, 37 and a father of two.

Portillo and his colleagues take half hour breaks when they start to feel nauseous or dizzy, but in the summer he sometimes stops work early, losing up to $60 for the three hours he misses.

"If it were up to our employer, we would keep on working - but we have to stop because the heat is unbearable," he said.

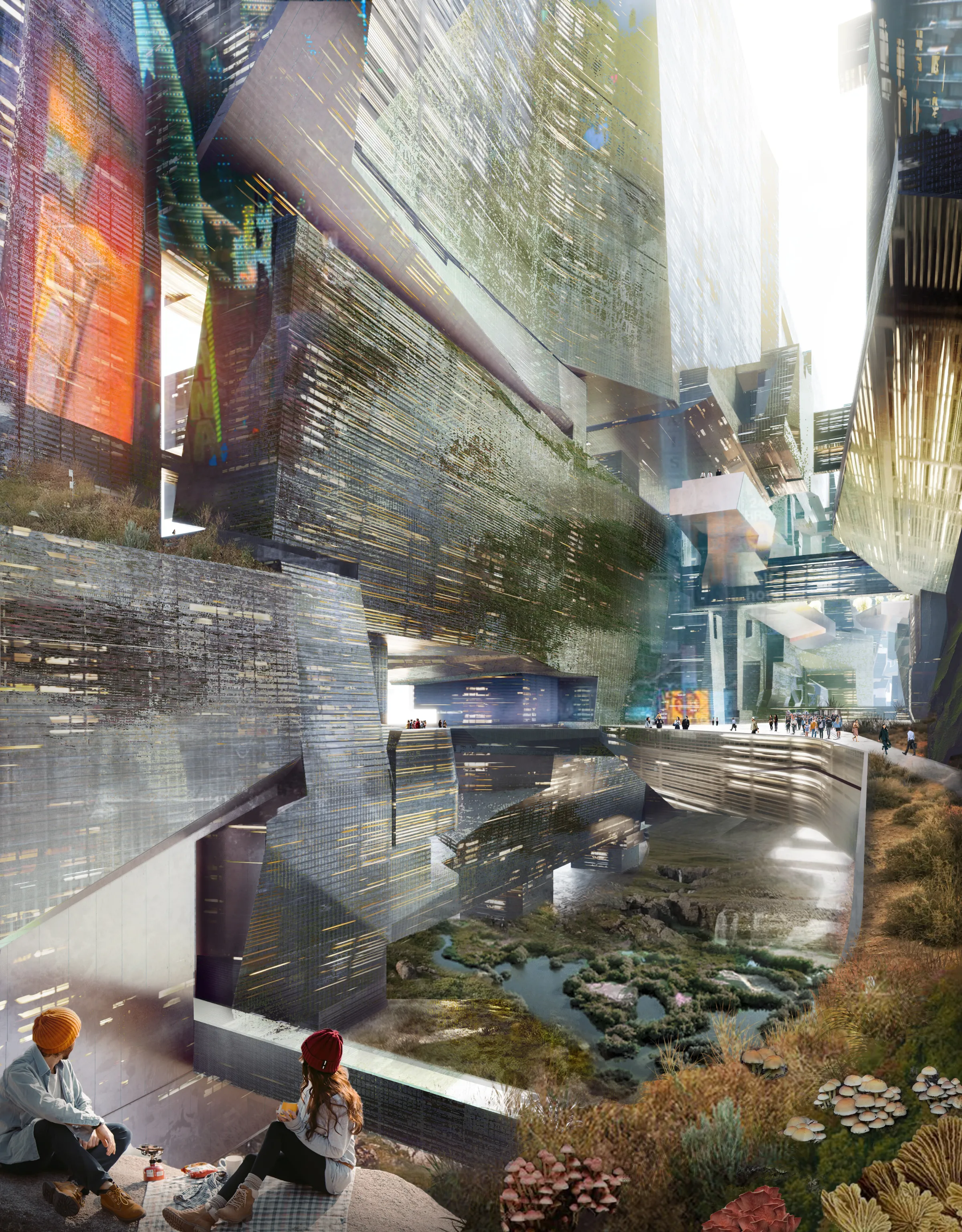

Farmworkers said they are forced to work under extreme heat without access to shade, regular breaks or fresh water. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Diana Baptista

Farmworkers said they are forced to work under extreme heat without access to shade, regular breaks or fresh water. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Diana Baptista

Fulcher said U.S. industry was losing nearly $100 billion a year due to workplace heat stress.

Labour productivity losses related to heat could reach nearly $200 billion by 2030, and $500 billion by 2050, a report by consultancy group Vivid Economics calculated.

The losses, said Fulcher, were due to workplace accidents, reduced productivity, absenteeism, higher worker's compensation payments, insurance costs, and damage to property and equipment.

"And they also lose money on, let's face it, lawsuits and public goodwill, which is what their business is based on in the first place. They're already losing money, and it would be much cheaper in the vast majority of these cases for them to put these protocols in place," said Fulcher.

In some industries, constant exposure to heat leaves workers fatigued and prone to mistakes that can cost lives, said Nathan Allen, who works in powerline tree clearance in Oregon and is affiliated with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers.

"If you're not 100% in body and mind, things get really dangerous, really quickly," he said.

The Biden administration's initial proposal in July would require employers to provide cool drinking water and paid break rests when the heat index, which measures what the temperature feels like, hits 80 F (27 C).

Additional measures like mandatory rest breaks of 15 minutes at least every two hours would be required at 90 F (32 C).

Business groups have argued such standards would add costs and that one-size-fits-all rules would not work in every industry.

U.S. Chamber of Commerce Vice President Marc Freedman said in comments submitted to the Department of Labor's Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in 2022 that "much of what makes an employee susceptible to heat illness is unpredictable, or out of the employer's control or knowledge, such as the employee's physical condition."

Retaliation

While working the sweet potato fields of North Carolina where temperatures have reached 110 F (43 C), José has experienced dehydration and dizziness, and even lost his toenails while working barefoot. Last year, he said a worker in the same field had died from heat stroke.

"We have to keep working regardless of how inclement the weather is. If you don't, you are fired and forced to sign a piece of paper saying you're not productive enough for the company," said José, who requested that only his first name be used for fear of retaliation.

Poor working conditions add to the effects of heat. José, a foreign seasonal worker on an H2A temporary visa, described working 40 hours a week without breaks, or access to shaded areas or clean water.

For such workers, getting fired means they cannot find another job in the country and their visa will not be approved next season - a massive economic hit for them and their families, as they can earn up to $500 a week.

"There is legitimate fear of employer retaliation, especially for workers who work on a piece rate, or workers who may be undocumented or on an H2A visa," said Alexis Guild with the advocacy group Farmworker Justice.

Migrants who complain about working conditions get fired, are not hired in following seasons, have their pay cut, and even receive physical threats, said Kerfoot, lawyer with the Centre for Migrants' Rights.

Migrant workers are protected by the same regulations as U.S. citizens, but the threat of retaliation silences workers across a myriad of industries, from agriculture to meat packing.

"The risk is so high that migrant workers are limited in their choice on what to do about a situation as difficult as working under extreme heat," Guild said.

Fighting back

Marcelo Tagle and his co-workers at a fast food chain have gone on strike to demand air conditioning in the kitchen, where temperatures get as high as 90 F (32 C).

"It is very stressful and uncomfortable to work under an unbearable heat in which you cannot even breathe," said Tagle.

But striking has only been partially helpful. Instead of AC, the restaurant installed fans which mildly cool the kitchen.

Federal law has a "general duty" clause requiring employers to maintain basic general safety standards, but enforcement is spotty and cases can be difficult to prove.

Even when workers know their rights and lodge a complaint, they can still come up empty. Frustrated by slow regulation, many workers are taking matters into their own hands.

Some told Context they were organising strikes to demand air conditioning and fans in their workplaces, or plan to collectively walk out of a job when temperatures are too high.

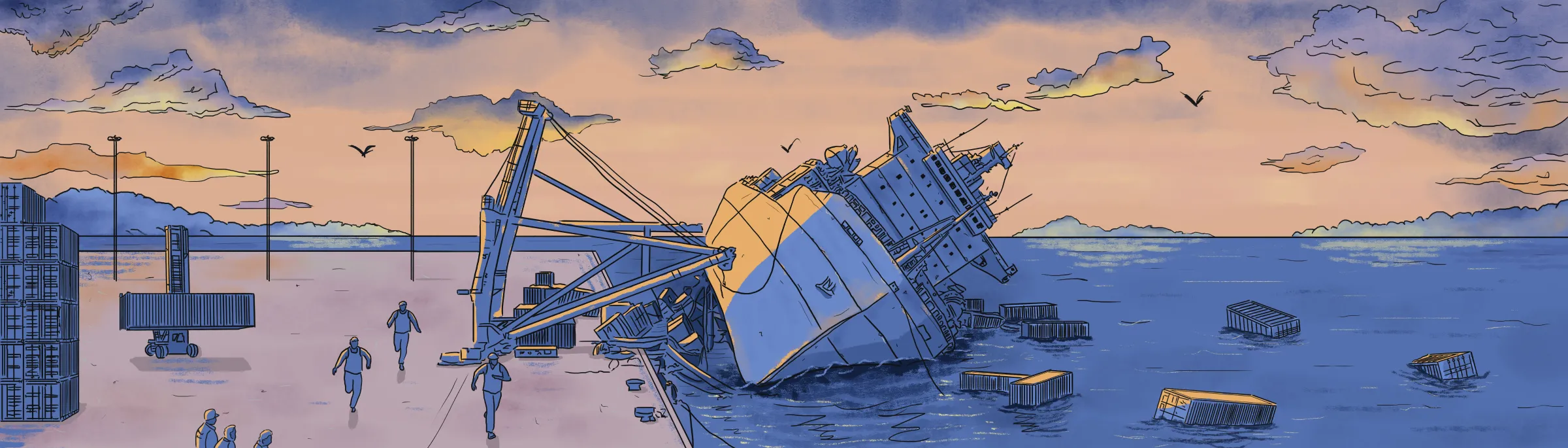

Workers in the U.S. have organized protests and strikes to demand employers with protections against extreme heat. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Diana Baptista

Workers in the U.S. have organized protests and strikes to demand employers with protections against extreme heat. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Diana Baptista

Farm workers are also boosting alternatives like the Fair Food Program, which strikes deals directly with major brands and consumers to guarantee workers safety from the heat.

In Texas, Veronica Carrasco distributes information to workers on how to work safely in extreme temperatures and helps them fight for consistent breaks.

Knowledge of the risks of heat means Carrasco turns down jobs that are dangerous and to avoid heat stroke she often takes unauthorised breaks.

"We keep believing and fighting for workers. We cannot work under extreme temperatures ... it is inhuman and it cannot carry on," said Carrasco.

Reporting: Diana Baptista and David Sherfinski

Editing: Jonathan Hemming

Graphics: Diana Baptista

Production: Amber Milne

Tags

- Extreme weather

- Gender equity

- Adaptation

- Climate policy

- Climate and health

- Workers' rights

- Corporate responsibility