U.S. firefighters on climate frontline face 'broken' health system

What’s the context?

As climate change makes wildfires fiercer and more frequent, firefighting work has never been more dangerous. But many U.S. federal firefighters feel let down by the system meant to protect them

Chris Carneal spent much of his working life fighting fires for the U.S. government, so when he was diagnosed with cancer he turned to a federal workplace compensation program for help to foot the bill.

Although his doctors said his kidney cancer was linked to smoke exposure from work, the program administered by the Department of Labor (DOL) initially refused to cover his care.

Carneal spent the last two years of his life struggling to pay medical bills and wrangling with a system that many firefighters say is failing to properly protect those who undertake one of the country's most dangerous and vital jobs.

A year before his death, Carneal pleaded via Twitter with then-President Donald Trump to pressure Congress to make it easier for firefighters to access care for chronic illnesses.

"Please help us," he wrote. "We give our life."

But it was only after Carneal's death in November 2020 that the DOL finally accepted his family's claim for work-related disease cover after concluding that his cancer was a result of his job fighting wildfires and other blazes.

For his wife, Dana, the hard-fought victory was "bittersweet".

Firefighters start a controlled burn near Sugarloaf as the Windy Fire expands in the Sequoia National Forest, California, U.S., September 26, 2021. REUTERS/David Swanson

Firefighters start a controlled burn near Sugarloaf as the Windy Fire expands in the Sequoia National Forest, California, U.S., September 26, 2021. REUTERS/David Swanson

"I was really disappointed they took so long and that he wasn't able to celebrate ... that win with us," she said.

"The whole time we were fighting for all this, he would always tell people 'I'm not looking for a ton of money ... I just want to pave the way for my brothers and sisters behind me if they should ever have to fight this fight'."

As climate change drives more frequent wildfires, firefighters for federal agencies like Carneal, a civilian who worked for the U.S. Army and fought scores of wildland fires, face a growing risk of work-related injury and illness.

But some find their claims for healthcare costs from the workplace compensation program get lost in a years-long bureaucratic process and sometimes are only paid or accepted after it is too late.

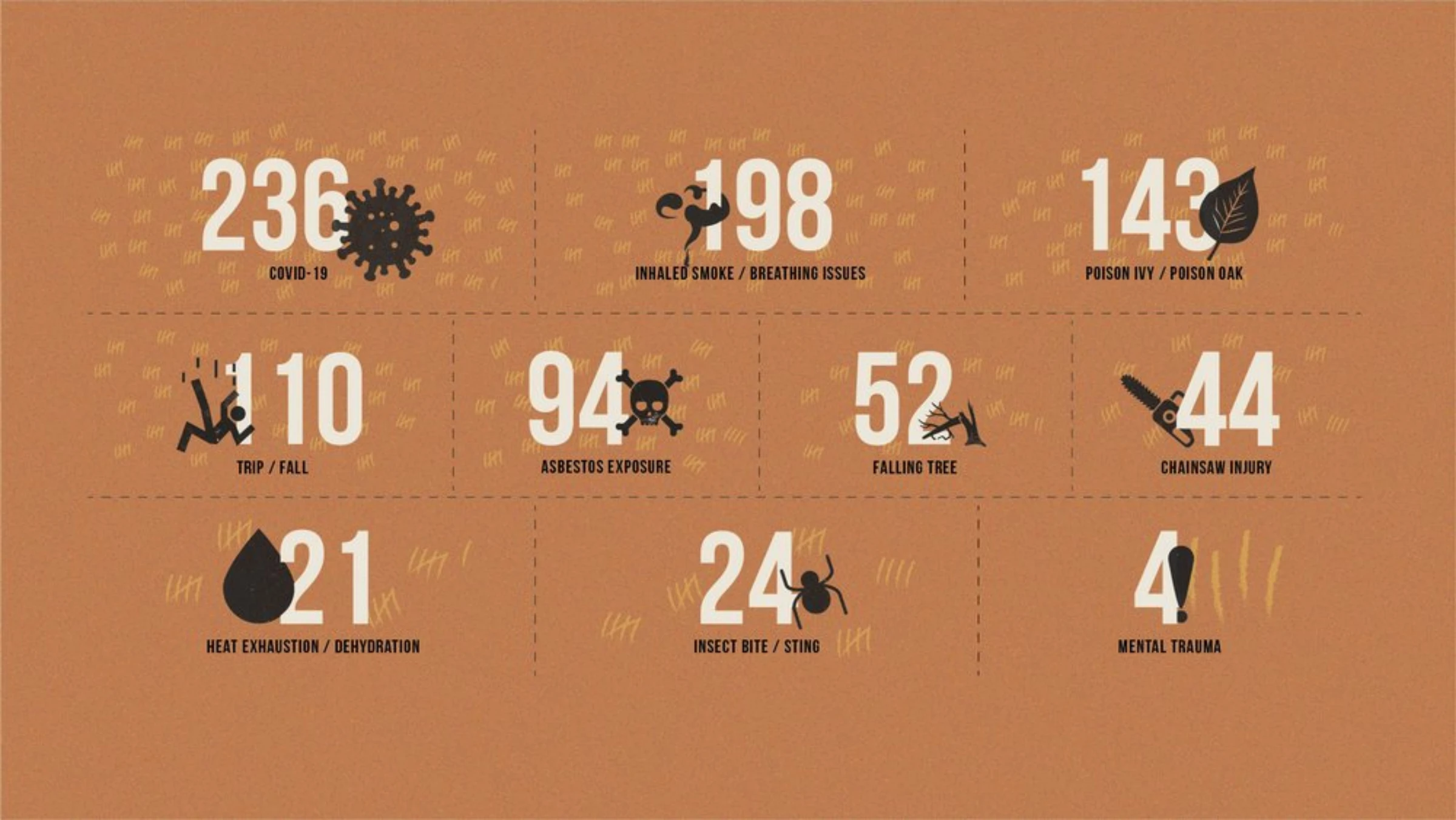

From 2017 to 2020, 2,500 work-related injuries or illnesses were reported on average each year by the roughly 10,000-strong U.S. Forest Service wildland firefighting force – the nation's biggest wildland force, a database provided to the Thomson Reuters Foundation showed.

"Our occupation is very risky, with high consequences ... We have to make sure we're taking care of people," said Kelly Martin, president of Grassroots Wildland Firefighters, a group lobbying for better workplace protections.

Too often, that is not the case, she said.

Number of injuries recorded by U.S. Forest Service wildland firefighting force 2017-2021

Number of injuries recorded by U.S. Forest Service wildland firefighting force 2017-2021

Federal firefighters are meant to have treatment for work-related health issues paid for by the government, but are often denied that care, more than a dozen current and former firefighters, their families, union officials and independent experts told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Case files, documents and medical records contain further criticism of the way in which the DOL - through its Office of Workers' Compensation Programs (OWCP) - handles claims from firefighters.

"It's a broken system," Martin said. "We're talking about systematic failures."

One firefighter, who like others requested anonymity for fear of reprisals, said he struggled to get the government to pay for the multiple surgeries he needed after he was hurt in a fall at the scene of a remote wildfire.

"It would've been way easier if I died on that mountain," he said.

Smoke exposure, panic attacks

Kirk McDusky, a member of the Prineville Hotshot Crew, walks past smoke rising from the Brattain Fire in the Fremont National Forest in Paisley, Oregon, U.S., September 18, 2020. REUTERS/Adrees Latif

Kirk McDusky, a member of the Prineville Hotshot Crew, walks past smoke rising from the Brattain Fire in the Fremont National Forest in Paisley, Oregon, U.S., September 18, 2020. REUTERS/Adrees Latif

From smoke exposure and exhaustion to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the Forest Service database paints a stark picture of the toll wildland firefighting work is taking on the firefighters on the frontlines of climate change.

"I worked from 6 a.m. until midnight at 9,000 ft (2,743 meters) elevation in temperatures reaching the mid 90s," reads one entry by a firefighter who was digging trenches to protect nearby homes.

A survey conducted by Grassroots Wildland Firefighters found that two-thirds of wildland firefighters had sought help for an injury or illness from a workplace compensation scheme.

For years, members of the U.S. Congress have pushed for federal legislation to make it generally accepted that certain diseases are caused by firefighting work.

That would make it easier for firefighters like Carneal to access workplace compensation.

Many state and municipal firefighters already benefit from such "presumption laws", meaning they get more extensive cover than is usually provided by standard employee health insurance, firefighter advocacy groups said.

Amid a brutal 2021 wildfire season in the western United States, lawmakers in Washington, D.C., last month presented new legislation to boost federal firefighters' pay and benefits.

Crucially for federal wildland firefighters, the proposals include creating a presumption that illnesses including heart disease and some cancers can be "proximately caused" by the job.

"This is a no-brainer – why would we want to treat our federal firefighters (like) second-class firefighters?" said U.S. Rep. Salud Carbajal, a California Democrat who has long pushed for a legislative fix.

The DOL said it accepts, roughly, at least 86% of the approximately 2,900 annual claims it has received from firefighters, on average, over the last 10 years, noting that anyone rejected has ample avenues to appeal.

In some cases, however, doctors are unable to establish a clear link between workplace exposure and a particular condition, said Christopher J. Godfrey, director of the DOL's OWCP.

He acknowledged dissatisfaction among some firefighters and said he understood why many want to see legislative changes that would make it easier for them to have claims approved.

But he said the workplace compensation program was not "adversarial" and aimed to help people get the benefits to which they are entitled.

"We're not an insurance company – we don't get a bonus for denying someone a claim ... (but) we can't accept a claim because we feel bad for the individual," Godfrey said by phone.

Many injured firefighters, however, said the existing system forces too many people to fight for the care they deserve.

In the Grassroots Wildland Firefighters survey, most reported a negative experience, and more than 40% said they did not get the care or benefits they needed.

'Damaged goods'

Firefighter Daniel Lyon lies in a hospital bed after 65% of his body was burned in a fire in Washington state, in this undated handout photo via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Firefighter Daniel Lyon lies in a hospital bed after 65% of his body was burned in a fire in Washington state, in this undated handout photo via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Wildland firefighting is one of the most dangerous jobs in the United States, especially as global warming drives more frequent and intense forest blazes, experts said.

"A lot of things can just immediately kill you - a falling rock, or falling tree, you can be burned alive," said Kathleen Navarro, a researcher at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) who is studying wildland firefighting.

They also face invisible risks, such as exposure to toxins, she added.

But those injured, sometimes seriously, have their claims evaluated by the OWCP in a similar way to other federal workers with much more minor ailments - from mail carriers with sprained ankles to admin employees with carpal tunnel syndrome.

"We're the tip of the spear - fighting fires, fighting climate change - we're wildland heroes," said Bob Beckley, a union official representing federal employees, including some Forest Service workers.

"But when we're hurt, we're treated like we're disposable, damaged goods."

Although the OWCP has a dedicated office to handle paperwork from the Forest Service, firefighters who have been through the claims process said there is a lack of specialized training about the particular risks they face.

A DOL spokesperson rejected such criticism, saying the OWCP trains all its claims examiners on the links between workplace exposures and different medical conditions.

Godfrey noted, however, that the organization was working with NIOSH to establish a new claims handling unit that could deal with more difficult cases, like those involving certain cancers.

It might help in "getting someone to a doctor (in a) more timely (way) to get some of those difficult medical questions answered", he said, praising the work of current claims handlers.

But establishing a clear link between firefighting work and a particular condition is not the only challenge faced by sick or injured federal firefighters.

If they miss some element when they file paperwork, or neglect to file paperwork after a minor injury that becomes more serious over time, firefighters can struggle for years to convince authorities to pay for their full care, said Beckley.

Administrative hiccups are also a common problem, he said.

One firefighting supervisor told Grassroots the OWCP had denied coverage to a firefighter who was bitten by a highly venomous spider while urinating near a fire scene, on the grounds that she had neglected to wear protective pants.

"I guess she was supposed to pee in her pants," the supervisor wrote, adding that the firefighter had to spend $4,000 of her own money on medical care.

A Forest Service spokesperson said compensation and claims specialists are dispatched to major fire scenes to help firefighters file any injury claims, but that they are ultimately decided by the DOL.

The spokesperson declined to comment on individual cases, but said the "physical, psychological, and social safety of employees is a core value (of the agency)".

'Begging for help'

A firefighter covers his face while battling the Butte fire near San Andreas, California September 12, 2015. REUTERS/Noah Berger

A firefighter covers his face while battling the Butte fire near San Andreas, California September 12, 2015. REUTERS/Noah Berger

Several firefighters' families said they had only managed to get healthcare costs paid after appealing to elected officials.

I am begging for help," Michelle Ochoa wrote in a letter to Sen. Ron Wyden, an Oregon Democrat in March 2016.

It had been over two years since her husband Richard "Wally" Ochoa, a 21-year Forest Service veteran, was hit by a falling tree while defending a small Idaho community from a wildfire.

His face and shoulder were ripped open, both legs were broken and he suffered lasting brain trauma.

Richard 'Wally' Ochoa, a 21-year Forest Service veteran, stands in this undated handout photo via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Richard 'Wally' Ochoa, a 21-year Forest Service veteran, stands in this undated handout photo via Thomson Reuters Foundation

After Ochoa was released from hospital, the family's doctors recommended a full course of treatment at a brain injury rehabilitation center, but the OWCP refused to pay, without giving a reason, Ochoa said.

It was only after Wyden's office intervened that a partial course of rehabilitation was cleared, Ochoa said.

When it comes to injured wildland firefighters, "the very least we can do" is make sure there's quick access to workers' compensation, Wyden said.

"Change needs to happen across the board, from increased pay and better hours to better health benefits," Wyden said in emailed comments. "This is basic decency every worker in America deserves, including our firefighters."

Another firefighter who broke nearly a dozen bones during a fall in a mountainous fire zone said he had a surgery denied while he was on the way to hospital – a decision that was overturned following the intervention of his local senator.

"It's criminal that people have to go to their senators to beg for help," Martin said. "It should've been a warning sign that things are broken."

Richard 'Wally' Ochoa walks down a hospital corridor after being hit by a falling tree while defending a small Idaho community from a wildfire, in this undated handout photo via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Richard 'Wally' Ochoa walks down a hospital corridor after being hit by a falling tree while defending a small Idaho community from a wildfire, in this undated handout photo via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Godfrey, of the OWCP, said some claims are initially rejected before being approved later when more information is submitted.

"A lot of times that initial denial will happen, but someone will come back within the next month or two with a better, rationalized medical report on causation," he said.

Since Ochoa's injury, his wife Michelle and son Alex said efforts to get his care paid for have turned into a full-time job, demanding hundreds of hours of their time.

The family has had to delay shoulder surgery, pay for ear procedures out of pocket, and rely on the native tribe they belong to for help paying for medication. Ochoa said the family's ordeal had led him to contemplate suicide.

"You are like trash - they put you out on the curb, like you aren't worth anything," Michelle said. "You can't fight fires anymore? You're useless to us."

Profound risk

Firefighters monitor advancing flames of Caldor Fire north of Highway 50 near the town of Sciots Camp, CA, U.S., August 28, 2021. REUTERS/Fred Greaves

Firefighters monitor advancing flames of Caldor Fire north of Highway 50 near the town of Sciots Camp, CA, U.S., August 28, 2021. REUTERS/Fred Greaves

Researchers with the U.S. government have long shown links between some cancers and careers fighting wildland fires, where firefighters often spend weeks in smoke-clogged areas.

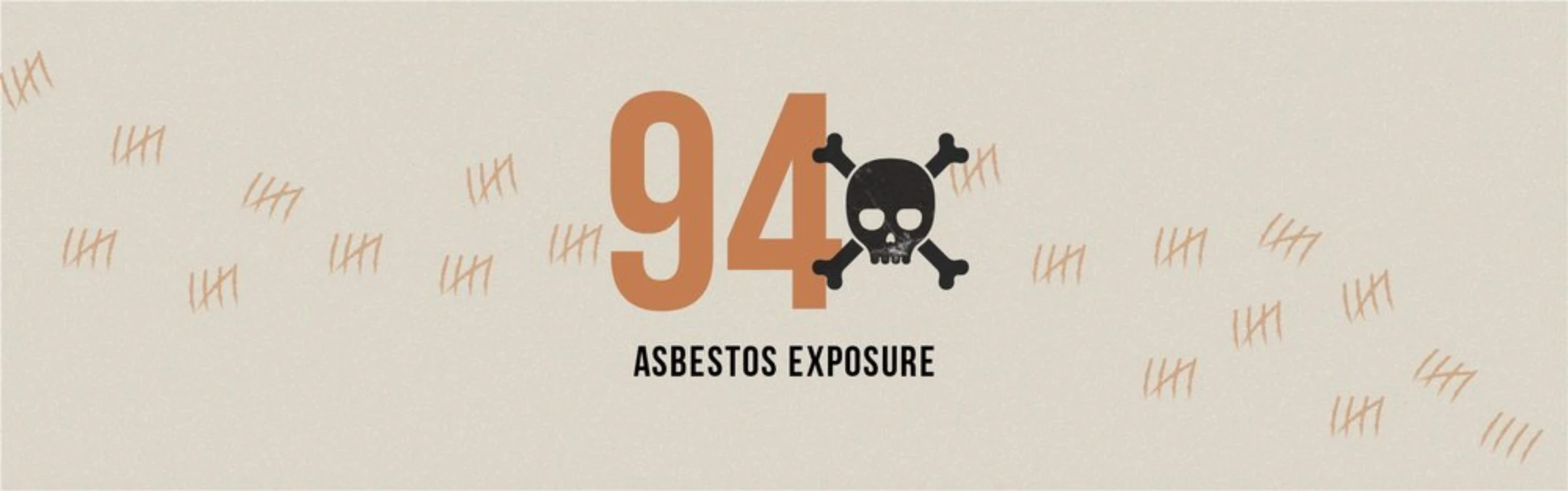

Fires in buildings or in forests can expose people to carbon monoxide, ammonia, sulphur dioxide, formaldehyde, and asbestos, among other toxins.

Forest Service firefighters have sought medical treatment costs for approximately 800 incidents or illnesses related to smoke exposure since 2017, the database shows, though experts said the true number was likely much higher.

Number of asbestos exposure injuries recorded by U.S. Forest Service wildland firefighting force 2017-2021

Number of asbestos exposure injuries recorded by U.S. Forest Service wildland firefighting force 2017-2021

"The risk is just profound," said George Broyles, a researcher who studies the health risks of wildland firefighting.

He co-authored a 2019 study that found a 10-year career led to a 22-24% increase in mortality from certain kinds of lung cancers and heart disease.

But despite such findings, federal wildland firefighters still have to prove such conditions are directly linked to their work.

Policy has not caught up to science, Broyles said.

Carneal, a former fire captain with Fort Carson Fire and Emergency Services in Colorado, and his doctors consistently maintained his cancer diagnosis at a relatively young age - early-to-mid 40s - was linked to the toxins he was exposed to as a federal firefighter.

His career working for the U.S. Army involved fighting more than 65 wildland fires, among other blazes.

The family was finally vindicated in July when the federal government accepted his claim on the basis of additional medical evidence and testimonials from Carneal's doctors.

Besides the emotional strain, Carneal's health problems took a heavy financial toll on the family. Facing hefty insurance co-payments for medical tests, the Carneals refinanced their home.

Asked about individual cases like Carneal's, the OWCP said privacy laws prevented it from discussing them without authorization.

'Travesty and dishonour'

Firefighters sleep by the roadside after fighting fires in Lake Hodges, near San Diego, California, October 23, 2007. REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson

Firefighters sleep by the roadside after fighting fires in Lake Hodges, near San Diego, California, October 23, 2007. REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson

Carbajal, one of a number of congressmen pushing to extend the "presumption law" benefits granted to state and municipal firefighters to their federal counterparts, called the disparate treatment a "travesty" and a "dishonor".

State, municipal and federal firefighters often work together at wildfire scenes, he noted.

A 2009 version of the legislation was projected to cost roughly $26 million over a 10-year period, according to Congress's budget scorekeeper - a tiny sum in the federal budget.

With wildfires raging from California to Texas and Washington this summer, pay for federal firefighters has also caught policymakers' attention.

President Joe Biden took steps over the summer to boost some firefighters' pay at least temporarily, calling the roughly $13-an-hour starting salary for some "ridiculously low".

Last month, U.S. Rep. Joe Neguse, a Colorado Democrat, introduced a bill to raise the annual wage for federal firefighters to at least $57,000. It also seeks to address complaints about the federal workplace compensation program.

"Getting treatment for work-related illnesses and injuries shouldn't be harder than fighting the actual forest fire," Rep. Katie Porter of California, a co-sponsor, told a congressional hearing.

Skeptical about finding support through official channels, some firefighters turn to charity organizations in an emergency.

"My phone rings 24/7 - I'll get calls when they're giving mouth-to-mouth on the forest floor," said Burk Minor, president of the Wildland Firefighter Foundation, which raises funds for firefighters in need.

In July 2018, Daniel Lyon wrote a note on his GoFundMe page - an online fundraising platform - updating the nearly 100 people who had donated

"About a month and a half ago, I received my 28th series of operations," he said. "I want to thank you all and appreciate each and every one of you."

It had been three years since the fire engine Lyon was riding in was engulfed in flames as he and his crew battled to protect remote houses threatened by a blaze in Washington state.

Lyon's three crewmates burned to death, and he staggered out of his fire engine, his entire body on fire.

Although his major surgeries were covered by OWCP payments, he struggled to get auxiliary services paid for, including massage to deal with the pain caused by burns over 65% of his body, and mental health counseling for PTSD.

"The bills just started piling up. Dealing with workers' compensation became my full-time job. I felt like I worked for them," he said.

"I don't think these higher-ups realize how screwed we are when we are injured on the job."

Like many injured firefighters, he turned to GoFundMe and private donors to make ends meet. The Wildland Firefighter Foundation helped him pay for the counseling he needed.

"We have to resort to nonprofits in our times of need - but those nonprofits are funded by donations from other firefighters," said Brandon Dunham, a former wildland firefighter who now hosts a podcast about the work.

Minor estimates his foundation alone allocates between $500,000 and $750,000 to the families of firefighters facing injuries and other hardships.

That is roughly 10% of what the Forest Service spent on medical care last year, according to numbers provided to the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

"People are afraid to speak up about this because they think they'll lose their jobs," Lyon said, a view echoed by half a dozen current and former firefighters.

A composite photo shows former firefighter Sara Brown (left) in a hospital bed and (right) walking on crutches, after breaking both legs parachuting into New Mexico to fight a fire in 2007, in this undated photo. Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

A composite photo shows former firefighter Sara Brown (left) in a hospital bed and (right) walking on crutches, after breaking both legs parachuting into New Mexico to fight a fire in 2007, in this undated photo. Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Former wildland firefighter Sara Brown has been wrangling with the OWCP for nearly 15 years since breaking both legs parachuting into a remote location in New Mexico to protect a cabin from a blaze in 2007.

"The OWCP process is incredibly adversarial," she said. "I had over 20-plus surgeries and procedures, many of which required multiple claims to be submitted. Many of those claims were denied, some repeatedly," she said.

Brown, who eventually had to have one of her legs amputated, said "not having treatments on the timeline that my doctors suggested would be most beneficial makes me wonder if long-term damage was done by waiting through the OWCP process".

The DOL spokesperson said the department had not heard complaints of "systemic failures" tied to the OWCP during recent outreach with groups representing federal firefighters.

The outreach has given officials an opportunity to hear about "the challenges associated with obtaining necessary medical opinions from physicians", the spokesperson added.

Brown, like many other firefighters, did not blame one individual or agency, pointing instead to factors including bureaucratic shortcomings and a lack of urgency to address the problem.

"There are no villains here," said Minor. "There are good-hearted people in these agencies."

But he said the situation was "only getting worse as the fire seasons get longer and longer".

"(Firefighters) are only humans, they're not machines," he added. "Something's got to give."

Reporters: Avi Asher-Schapiro and David Sherfinski

Text editing: Helen Popper and Laurie Goering

Graphics: Nura Ali

Producer: Amber Milne

This story was updated on Friday 12 November 2021 16:37 GMT to correct details of Sara Brown's amputation.