Trafficked cyber scam victims in SE Asia freed but cannot get home

Multinational victims of scam centres queue to get food at a shelter as they wait for their embassies to pick them up, in Tak province, Thailand February 19, 2025. REUTERS/Chalinee Thirasupa

What’s the context?

Rescued from cyber-scam centres in Southeast Asia, trafficking survivors find themselves mired in process of getting back home.

- Hundreds of thousands of victims trapped in scam compounds

- Cyber-crime economy contributed to $8 trillion losses in 2023

- Experts concerned that rescue efforts will discontinue

BANGKOK - Most of Jaruwat Jinnmonca’s anti-trafficking work used to focus on helping victims swept into prostitution.

Now, survivors of cyber-scam compounds dominate his time as founder of the Thailand-based Immanuel Foundation.

Hundreds of thousands of victims are trapped in cyber-crime scam farms that sprung up during the COVID-19 pandemic in Southeast Asia, according to the United Nations.

Conditions are reported to be brutal, with the detainees ruled by violence.

Photos on Jinnmonca’s phone show victims with purple and blue bruises, bleeding wounds and even the lifeless body of someone who had been severely beaten or was dead.

He has received reports of seven killings from inside compounds this year alone and reports of other forced labourers killing themselves, worn out from waiting for help that may never arrive.

“They want to go back home," he said, and if they do not follow orders, the gang leaders "will abuse them until they die.

“Some, when they cannot escape, they jump off the seventh or 10th floor. They want to die," he said.

Criminal gangs cashed in on pandemic-induced economic vulnerability and even now, workers come from as far as Ethiopia and India, duped into thinking a paid-for journey to Thailand will yield a worthwhile employment opportunity.

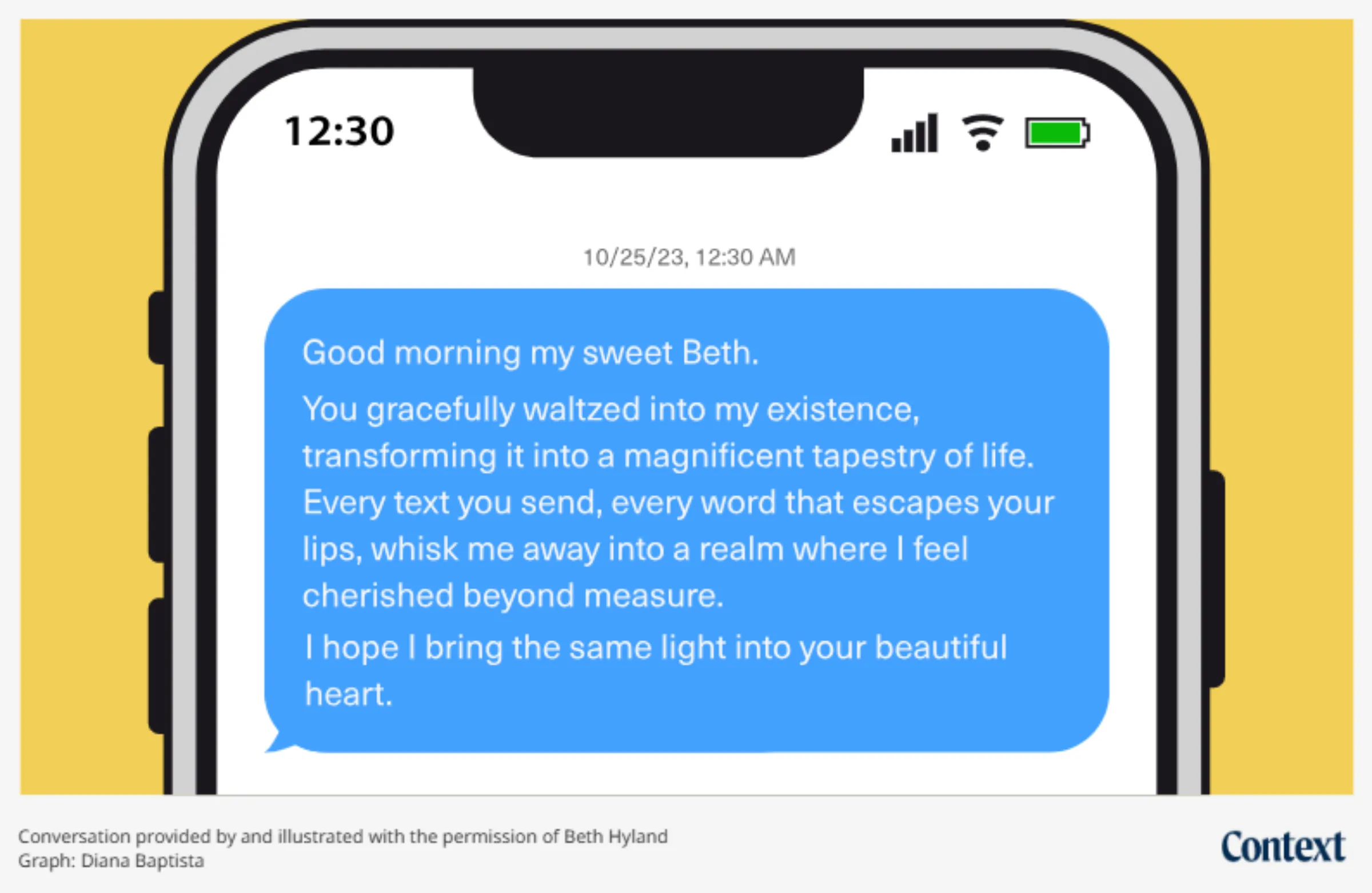

Instead they spend their days tethered to technology, generating fake social media profiles and compelling stories to swindle money from unsuspecting people, contributing to a cyber-crime economy that accounted for $8 trillion in losses in 2023.

In February, under pressure from China after a well-known Chinese actor, Wang Xing, was trafficked, Myanmar authorities and the Thai government collaborated in the biggest rescue operation yet.

By shutting down the internet and stopping fuel supplies and electricity in Myawaddy, Myanmar, authorities were able to debilitate several compounds, leading to the release of more than 7,000 workers.

Their ordeal, however, is not yet over. Many of them are waiting to be repatriated in holding centres where access to food and medicine is said to be scarce.

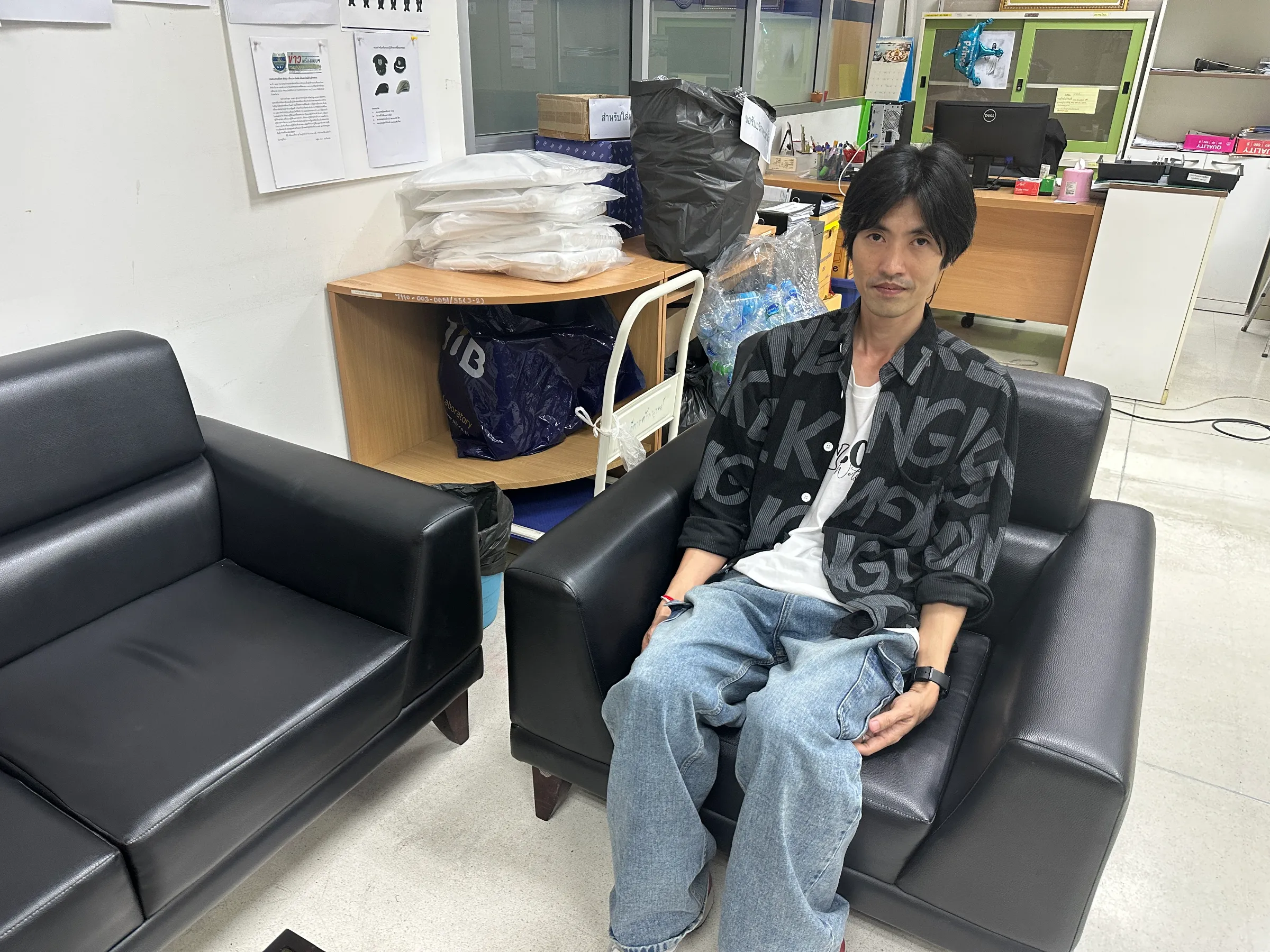

Jaruwat Jinnmonca, founder of Immanuel Foundation, received numerous messages everyday from people trapped inside scam centres looking for help, March 11, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Rebecca L Root

Jaruwat Jinnmonca, founder of Immanuel Foundation, received numerous messages everyday from people trapped inside scam centres looking for help, March 11, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Rebecca L Root

Rescue efforts

The Immanuel Foundation has rescued more than 2,700 people since 2020.

“We bring them to hospital for a health check and then take them to talk to law enforcement,” Jinnmonca said, as his phone vibrated for a third time in just 30 minutes.

The call was from one of his 12 staff members reporting that the team succeeded in extracting a Thai woman from a scam centre in Cambodia.

She was covered in scars from beatings but otherwise healthy, the team said.

Escaped workers say they were given little food or clean water and threatened with beatings or death if quotas were unmet.

For Palit, 42, a former clothing shop owner from northern Thailand, the risk of electric shock was never far away during his six-month detention.

He had been attracted to the promise of a high-paying administrative job in South Korea but instead was flown to Mandalay in Myanmar.

Fearing he was being trafficked for his organs, it was a relief to know he could keep them, he said.

Instead he was forced to spend his time creating fake profiles to engage a minimum of five people every day in online relationships.

“I would talk to the target like ‘Baby please invest in this, you will get good profit,’” said Palit, who wanted only his first name disclosed.

Well known among forced labourers, Jinnmonca’s personal Facebook pings with messages, typically four new people each day, begging for help and sharing stories like Palit's.

Is help coming?

The cross-border nature of trafficking rescue makes the repatriation process difficult and slow, said Amy Miller, regional director for Southeast Asia at Acts of Mercy International, which supports survivors.

“They are complaining about the wait time," she said. "There are people who are sick that are maybe not getting treatment.

“It's just a tinder box ready to go up in flames.”

The problem of how to process and provide for so many victims is deterring Myanmar’s law enforcement from further rescue operations, Miller said, so the potential for future operations is unclear.

“I don't feel super confident that this is actually a reform of the compounds or that they're going to shut down,” she said.

Targeting workers

Jinnmonca said he believes the most effective way to protect against trafficking and the scams is to imprison the masterminds at the top.

“If [we do] not fix this problem, it will only double,” he said.

Instead, he said, the workers are targeted by authorities.

When Palit, who is soft-spoken and quick to smile, was released from a scam centre in November 2023 alongside 328 other people, 10 of them were arrested.

They were accused of being complicit in cyber crime and kidnapping because their language skills gave them leadership roles in the compound’s living quarters.

But they were victims as well, said Jinnmonca, and such arrests mean workers rescued from the clutches of criminal gangs in one country may face prison in another.

(Reporting by Rebecca L Root; Editing by Amruta Byatnal and Ellen Wulfhorst.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Disinformation and misinformation

- Tech and inequality

- Tech regulation

- Social media