Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

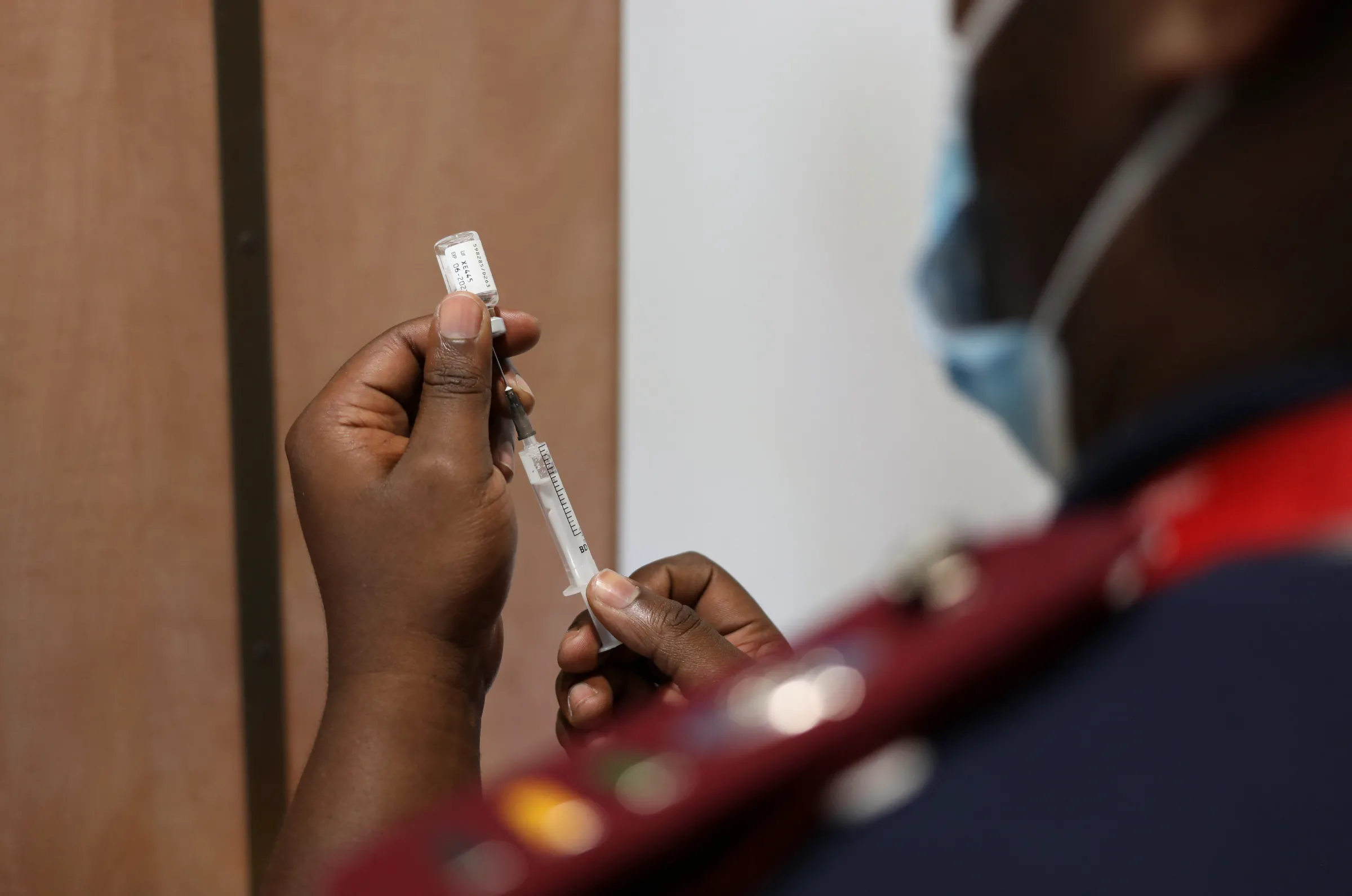

A nurse prepares a dose of a COVID-19 vaccine as the new Omicron variant spreads, in Dutywa, in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa November 29, 2021. REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko

Developing countries want the right to make their own COVID-19 vaccines, but opponents say there are better ways to boost supplies

By Emma Batha

LONDON - The emergence of the Omicron variant has reignited calls for patent waivers for COVID-19 vaccines to help developing nations get more jabs in arms as they battle to control the pandemic.

Supporters say a waiver would save lives in poorer countries and help prevent the emergence of more deadly and resistant variants that could pose a threat across the world.

But a handful of wealthy countries and major drug makers oppose such a move, saying it would harm future vaccine development.

Alarm over the spread of the Omicron strain has highlighted what the World Health Organization (WHO) has called "vaccine apartheid".

Low-income countries have only received a tiny fraction of the 8 billion doses administered globally in the last year.

As richer nations ramp up booster drives, some countries have not yet vaccinated even 1% of their population.

India and South Africa first proposed a temporary waiver to intellectual property (IP) rights for COVID-19 vaccines and treatments at the World Trade Organization (WTO) in October 2020.

Known as the TRIPS waiver in reference to the WTO's Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property agreement, it would give low- and middle-income countries the right to make their own vaccines.

More than 100 countries back the proposal for sharing technology and know-how, including the United States, which reversed its position in May.

They say there cannot be a repeat of the early years of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, when a lack of access to life-saving medicines cost millions of African lives.

The WHO and many former world leaders and Nobel Laureates are also pressing for a waiver, along with hundreds of aid agencies, civil society and human rights groups.

With COVID-19 having already claimed more than 5 million lives, many accuse those blocking the proposal of protecting big pharmaceutical firms' profits at the expense of public health.

Opponents include the European Union and countries including Britain and Switzerland, which host pharmaceutical firms.

Major COVID-19 vaccine companies include Pfizer and its partner BioNTech, Moderna, Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca.

They are generally against waiving their IP rights, although Moderna has said it will not enforce its COVID-19 vaccine patents during the pandemic.

Pharmaceutical companies say vaccine development is unpredictable and costly, and that strong IP protection helped drive the development of COVID-19 vaccines in record time.

A waiver could undermine efforts to adapt vaccines to new COVID-19 strains and impact research and investment for future medical innovation, they say.

However, supporters of a waiver argue that large amounts of public money also helped fund the development of the COVID-19 vaccines.

Vaccines normally take more than a decade to develop, but the first COVID-19 vaccines were ready within 12 months of the virus first being identified in China in December 2019.

Drug companies say a waiver would not fix the immediate problem of boosting supply in poorer countries, which would need time to set up manufacturing capacity.

They also argue that complex vaccines require strong cooperation between developers and manufacturers, and waivers could make it hard to control quality.

New variants are most likely to emerge in countries with low inoculation rates.

The Omicron strain was first reported in South Africa, where less than a quarter of the population has been vaccinated.

Public health experts say its emergence is evidence the world will not be able to beat the virus unless developing nations can access affordable vaccines.

U.S. President Joe Biden said Omicron underscored the importance of moving quickly on waivers.

The EU and other waiver opponents favour using flexibilities in existing WTO rules that permit countries to apply for "compulsory licensing" in a health crisis.

This allows countries to grant licences to manufacturers without the consent of the patent-holder, although they would still receive compensation.

Bolivia is trying to use this process to get 15 million doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine manufactured by a Canadian company.

However, compulsory licences are complex and time-consuming to apply for.

The EU has suggested simplifying the rules. Compensation could be kept to a minimum to ensure affordable prices.

Its proposal is part of a wider plan that would also encourage vaccine developers to enter deals with producers in developing countries and pledge increased supplies to vulnerable nations, as some have done.

The issue was due to be discussed at a WTO summit in Geneva starting on Nov. 30, but this was postponed due to new travel restrictions related to Omicron.

Since a waiver would need agreement from all 164 WTO members, it is now widely seen as out of reach.

WTO Director-General Okonjo-Iweala has called on members to redouble efforts to find a compromise by the end of February.

"The new Omicron variant has reminded us once again of the urgency of achieving equitable access to vaccines in every country in the world," she said.

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles