'I will keep marching': the view from Madagascar's streets

A protester reacts near a burning debris during a nationwide youth-led demonstration over frequent power outages and water shortages, in Antananarivo, Madagascar, October 7, 2025. REUTERS/Zo Andrianjafy

What’s the context?

Why are Antananarivo's young people on the streets? A protest organiser explains.

- Madagascar one of the world's poorest countries

- Malagasy youth call for an end to corruption

- Despite police violence, protesters vow to keep marching

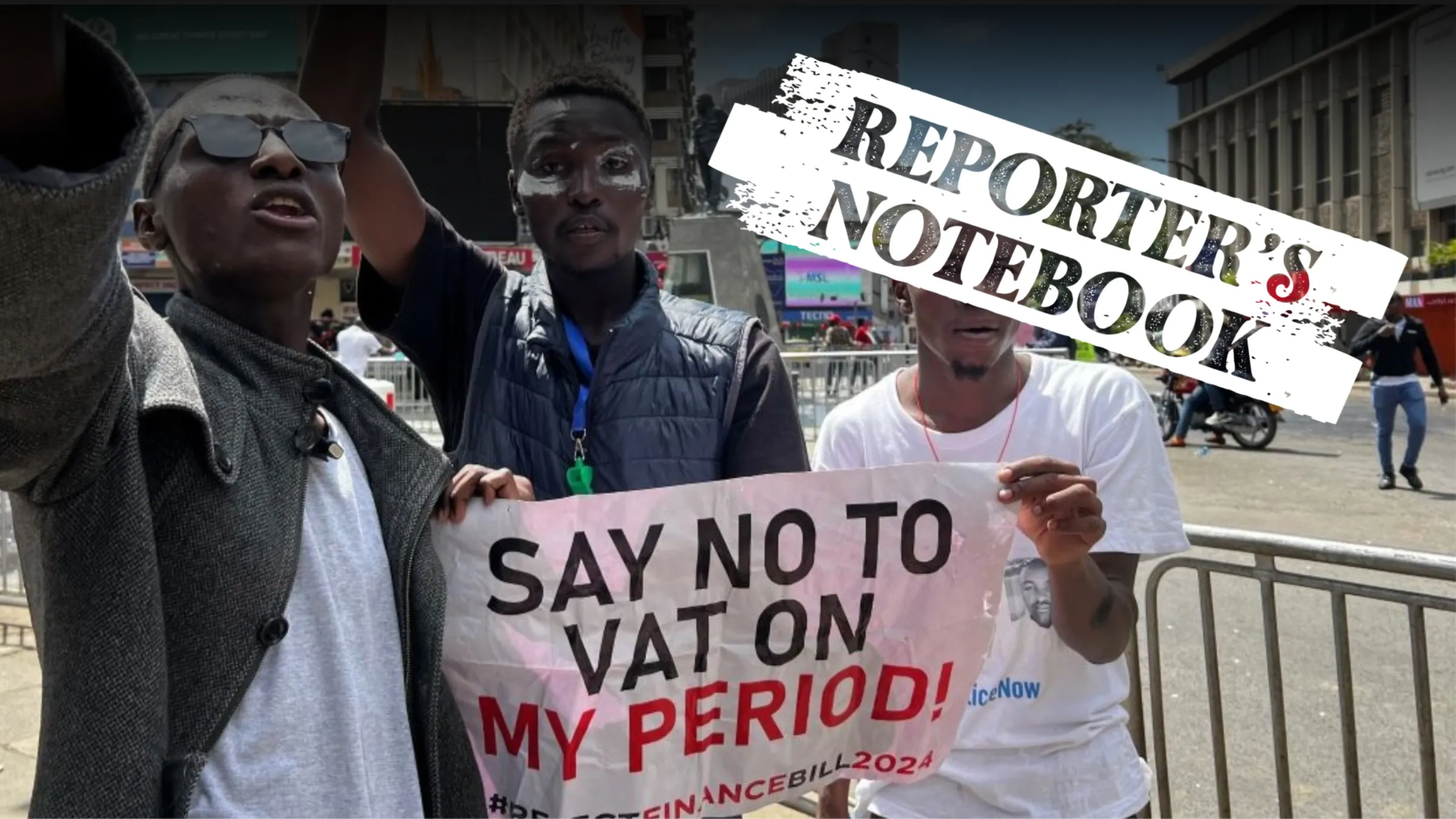

JOHANNESBURG - Inspired by Gen Z uprisings from Nepal to Kenya, tens of thousands of young Madagascans have taken to the streets in recent weeks to demand an end to broken promises, bust services and bankrupt rule.

The island nation - home to rich minerals and fertile land - is one of the world's poorest, and demonstrators blame corruption at the top for a life they say is blighted by ceaseless power cuts, deep poverty and a dearth of opportunity.

The United Nations say at least 22 people have been killed in more than three weeks of protests - some by security forces and others by gangs with no link to the demonstrations.

Protesters say the number is higher.

Despite boasting significant mineral wealth, biodiversity and fertile farm land, Madagascar saw its income per capita fall 45% in the 60 years that followed independence in 1960.

President Andry Rajoelina - himself no stranger to street protests - came to power in a 2009 coup, promising reform.

Now, the former DJ and media mogul is on the receiving end of popular anger and last month had to dissolve his government in response to protesters' demands.

This week he appointed an army general as prime minister and promised a "national dialogue" with spiritual leaders, students, youth representatives and others to hear their concerns.

Inspired by similar "Gen Z" actions - potent, youth-led movements often organised with speed on social media to fight inequality and corruption - the protests are the largest wave of unrest on the Indian Ocean island nation in recent years.

Context spoke to one of the protest organisers, 29-year-old Patrick, who asked to go by a pseudonym to protect his safety.

Here's his first-person account of life on the ground.

It started on Facebook Live.

The people who initiated the movement sent a live video inviting everyone to join them.

People joined because, here in Madagascar, we can't express our voices. When we speak about the reality, they put us in jail.

And the reality is that our water and electricity can cut out five to eight times a day.

News of the protests spread on Facebook and also TikTok.

At the beginning of his mandate as a president in 2018, Rajoelina said there would be no more electricity and water cuts and we are waiting every day, every day, and it's the same situation from his first mandate till now.

So the citizens are tired of his empty promises.

Before the protests started, the police took to the streets, waiting. We always called for peaceful protests. People gathered from all over the capital Antananarivo.

The police tried to block us, they used real bullets to fire into the crowd to try disperse us. They used tear gas.

I saw a one-month-old baby shot at with tear gas. The baby died the next day.

Soon looters started to attack malls, burning and stealing from the buildings. These were not protesters. We believe they were paid by government to discredit our peaceful movement.

But we continue to peacefully protest. It grew from just young people but now we have been joined by politicians, influencers, singers.

It's hard to know the exact figures, but I estimate at least 10,000 people protested in Antananarivo alone. In every capital of every province there were more protesters.

So the water and electricity were triggers, but we are protesting the whole political system.

The omnipresence of corruption affects all levels of government, but especially at the top.

But we are determined to keep demanding change, because it's our right to protest, it's in our constitution, in our law. Everyone should have the freedom to express themselves and not to be repressed by the government.

So what are we asking for?

We demand the full participation of young people in policy-making and national decision-making. We demand an end to nepotism and corruption - the separation of state and family privileges.

We demand transparency and equal opportunities. The right to peaceful protest and to be able to gather and express oneself without fear of violence. An end to threats and manhunts against those who speak out. Investigations into violence committed by law enforcement.

And a public apology from the president for this act of violence.

We call for urgent involvement of the African Union and the United Nations for impartial mediation and the protection of protesters.

I will keep marching.

I am afraid for my safety but I will face this fear for my future children to live in a better Madagascar.

For now, its a matter of survival. We are fed up. We have seen our future compromised and we demand to be involved in all the decisions that affect out country and our lives.

We won't stop protesting until we see that change.

(Reporting by Kim Harrisberg; Editing by Lyndsay Griffiths.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles