Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Venezuelan migrant Macyuli, traveling with her four children and husband, and other Venezuelan families, walks along the jungle path through the Darién Gap carrying her daughter. Darién Gap, Colombia, July 27, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

Panama's plan to cut off the dangerous migration route will collide with the desperation of people seeking a better life in America

Panama's new president, José Raúl Mulino, has vowed to stop hundreds of thousands of migrants travelling through the Darién Gap - a treacherous stretch of jungle straddling Colombia and Panama.

Just minutes after his inauguration on July 1, Mulino's government signed an agreement with the United States to halt illegal immigration through the Darién, a remote stretch of land that has become one of the world's most dangerous migration routes.

Under the agreement, the United States will cover the cost of deportation flights from Panama, which are expected to start in two to three months.

Panama's Public Security Ministry announced in July that barbed wire fencing had been placed to block at least five paths in the Darién Gap that spans about 100 kilometers (62 miles) across mountainous terrain.

Having traversed a stretch of the Darién Gap on the Colombian side when I walked alongside migrants in 2022, I can say that Mulino's plan has little chance of succeeding.

It's virtually impossible to close off the jungle.

No amount of barbed wire will be enough to stop migrants heading north to the United States in search of a better life.

Last year, a record half-million migrants risked their lives trudging through the rainforest on foot. So far this year, more than 170,000 migrants have crossed the Darién Gap, many of them families with children, Panamanian authorities have said.

Two years ago, I set off from the Colombian tourist beach town of Capurganá to walk with a group of people on the first part of their seven-day journey across the Darién.

Traversing slippery muddy trails through dense tropical forest, I spoke with numerous migrants, many of them looking for decent jobs and secure lives. Others hoped to reunite with family already living in the United States.

There were the two young brothers from a poor Nepalese farming family, numerous Venezuelan families with toddlers escaping an economic and political crisis in their homeland, and men driven from their homes by violence and conflict in Cameroon, Haiti and Afghanistan.

And there was Arnola, a former Congolese boxing champion travelling with three nephews and nieces under the age of 12 and a sister-in-law who was five months pregnant.

I walked right behind him and felt a huge sense of relief when he slashed a snake in half that had crossed my path with his machete.

I remember the long queues that would form at the summits of steep hills as exhausted migrants briefly rested to catch their breath.

Held down by heavy bags and bottles of water, migrants, some in beach sandals or barefoot, would struggle to find the strength to carry on.

They were all bound by the same insatiable determination and hope to reach the United States for a stab at the American dream.

Some attempts prove fatal. On July 24, Panamanian border police reported 10 migrants were found dead after drowning in a river as they made their way through the rainforest.

Despite the dangers, paths for migrants will remain open.

That's because this remote lawless stretch of jungle isn't under the control of Colombian or Panamanian security forces.

The Colombian side of the Darién Gap lies in the Urabá region, which is a major cocaine trafficking route.

It's largely run by the powerful Gulf Clan drug cartel, one of Colombia's largest organised crime gangs, which controls who enters the Darién Gap and a large chunk of the human smuggling business.

To stop the flow of migrants, governments would have to take on the cartels who have a vested interest in keeping the Darién Gap open.

Panama's president has alluded to the problem.

"I won't allow Panama to be an open path for thousands of people who enter our country illegally, supported by an international organisation related to drug trafficking and human trafficking," Mulino said after he was sworn in as president.

For Colombian smugglers, who call themselves "humanitarian guides," this is a highly profitable business.

Back in 2022, I witnessed smugglers charging migrants about $160 each to be led through the Darién Gap to reach Panama.

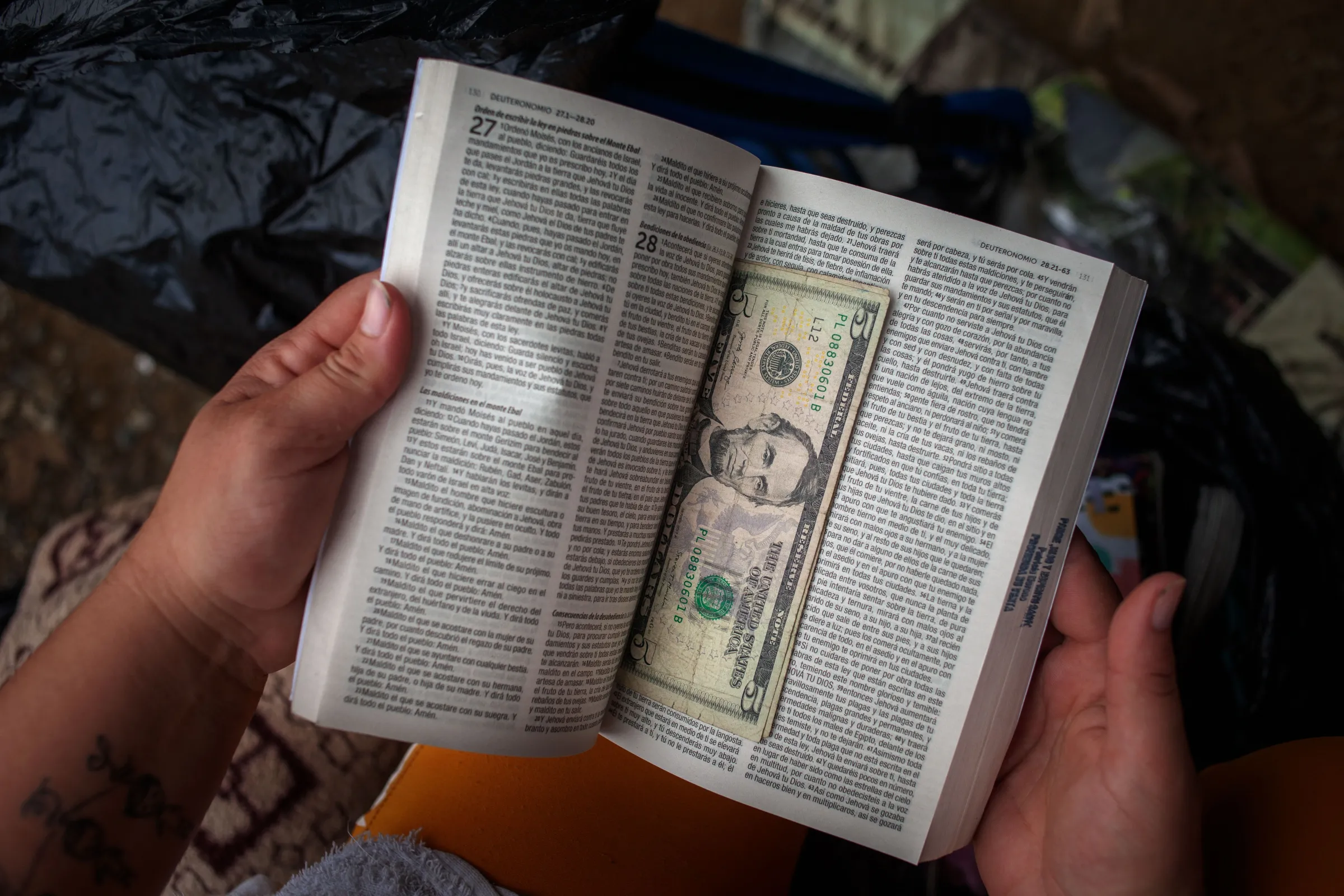

Dollar bills, some stashed away in Bibles, were scraped together by migrants and handed over to guides before setting off.

Based on a conservative estimate of 500 migrants crossing the Darién Gap daily, the guide business is worth $80,000 a day.

A Venezuelan migrant hides dollar bills in a bible carried in her backpack before negotiating a fee with jungle guides to take her and her family through the Darién Gap at a camping site in the Colombian town of Capurganá where migrants gather before setting off on the jungle trek. Migrants pay about $160 each to be led through the Darién Gap to reach Panama. Capurganá, Colombia, July 27, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

A Venezuelan migrant hides dollar bills in a bible carried in her backpack before negotiating a fee with jungle guides to take her and her family through the Darién Gap at a camping site in the Colombian town of Capurganá where migrants gather before setting off on the jungle trek. Migrants pay about $160 each to be led through the Darién Gap to reach Panama. Capurganá, Colombia, July 27, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

When there's a crackdown on migrant routes, smugglers respond by raising their fees. The barbed wire will be cut down, and new, longer and more dangerous routes introduced.

Already, there isn't just one way or path to reach Panama through the Darién. Several different routes and starting points along Colombia's coastline exist, with fees and the time taken to cross varying.

It's also difficult to close a shared border when the other side isn't on board.

Colombia's left-wing president, Gustavo Petro, has criticised Panama's attempt to close the Darién route.

"Barbed wires in the jungle will only bring drowned people into the sea," Petro tweeted on July 9 on his X account.

Panama's crackdown on illegal migration may slow the flow temporarily, but thousands of migrants will continue to get through.

Both smugglers and migrants will always find a way by foot or by sea, such is their desperation, and the pull of the American dream.

(Reporting by Anastasia Moloney; Editing by Ayla Jean Yackley.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles