COP27: How can the world fund the growth of nature protection?

A man looks out at the cloud forest standing atop a canopy at the buffer zone of Manu National Park in front of Huayquecha Biological Station near Paucartambo, Cusco December 5, 2014. REUTERS/Enrique Castro-Mendivil

What’s the context?

Too little money flowing to on-the-ground forest protectors and low carbon prices may impede progress, climate change experts say

- Forest conservation unites climate and nature agendas

- More countries are backing '30x30' land and oceans goal

- Nature-rich nations seen needing more financial incentives

SHARM EL-SHEIKH, Egypt - A push to conserve 30% of the planet's land and oceans by 2030 - a key pillar of a new global nature pact due to be agreed next month - has gained the support of about 112 nations, a big boost from 70 a year ago, leaders said at the COP27 climate summit.

But achieving that goal will be a challenge, they admitted - not least because countries that safeguard their nature get too few rewards for work that has a universal payoff, from storing climate-changing carbon emissions to protecting wildlife.

"We are providing a free service to the world without benefiting much from it," Tanzanian President Samia Suluhu Hassan - whose country has launched a national tree-planting drive - told a COP27 event on forest protection.

Interest among businesses in funding nature protection to help offset their own planet-heating emissions is surging, forest experts said, but channeling that money to people on the ground doing the work remains complicated, Hassan said.

She said her country had not gained from carbon credits, which require substantial measuring, verification and technical know-how "we don't have".

Protecting 30% of the planet by 2030 - the so-called "30x30" conservation goal - is seen as the cornerstone of a new global nature pact set to be finalised at a separate U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity summit (COP15) in Montreal, just a month away.

The COP27 climate talks, from Nov. 6-18, also mark a year since about 140 countries pledged to halt deforestation by 2030 at COP26 in Glasgow.

With growing awareness that limiting global warming will demand protecting nature - and vice versa - the overlap between the two COP gatherings is growing, with a heavy push for nature evident this week in the Egyptian resort of Sharm el-Sheikh.

More than 25 countries at COP27 on Monday launched a group called the "Forest and Climate Leaders' Partnership", which they said would ensure they hold each other accountable for the promise to end deforestation by 2030.

Private companies announced $3.6 billion in new funding toward the effort and, among governments, Germany pledged to double its spending on forest protection.

"We know there's no pathway to net-zero (emissions), no credible solution to climate change, that does not involve nature," said Zac Goldsmith, a minister of state in Britain's foreign affairs and development ministry.

Rainforests like the Amazon, for instance, not only store carbon but provide other crucial services, including regulating the rainfall that is vital for global food security.

If forests and other ecosystems continue to be damaged and even disappear - largely as agriculture expands to meet rising global demand for food - irreversible climate tipping points could be passed, scientists have warned.

"Nature is very, very resilient but humanity is very, very aggressive," noted Christophe Béchu, France's minister for ecological transition and territorial cohesion.

"If we don’t create some sanctuary, we won’t be able to succeed in fighting efficiently against global warming."

Steps forward

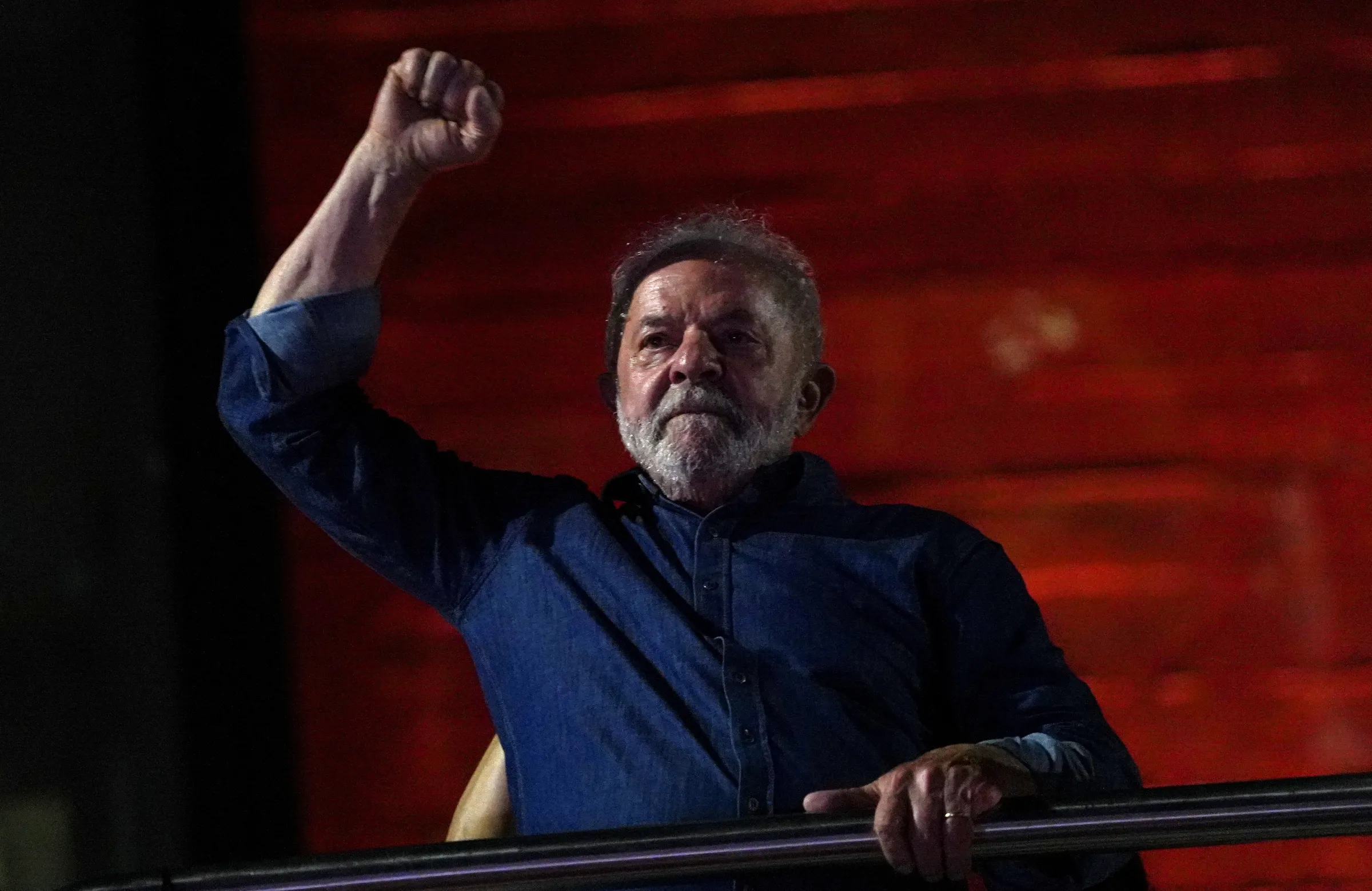

A few positive signs are emerging, officials and nature experts said. In Brazil, for example, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva last week defeated incumbent far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, whose backing of agriculture and mining in the Amazon has led to soaring forest losses.

President-elect Lula has pledged to "fight for" net-zero deforestation - although he faces a heavy political lift.

Colombia in August reached its "30x30" goal early, with 34% of the nation's land and seas put into protected areas after securing financial help from Britain and philanthropists, said former President Ivan Duque.

Deforestation in Indonesia, home to the world's third-largest tropical forests, also is at a 20-year low, while Africa's Gabon has committed to protecting the Congo Basin forests that cover nearly 90% of its land, forest experts said.

But boosting the number of countries willing to step up nature conservation will likely require economic incentives, such as access to international funding, including through carbon markets.

That finance could replace the money countries and communities might otherwise make cutting down their forests, providing motivation to keep them standing, the experts added.

An indigenous woman and her child walk in near-pristine Amazon rainforest in Colombia’s southeast Amazonas province, Miriti- Parana, Colombia, December 20, 2021. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

An indigenous woman and her child walk in near-pristine Amazon rainforest in Colombia’s southeast Amazonas province, Miriti- Parana, Colombia, December 20, 2021. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fabio Cuttica

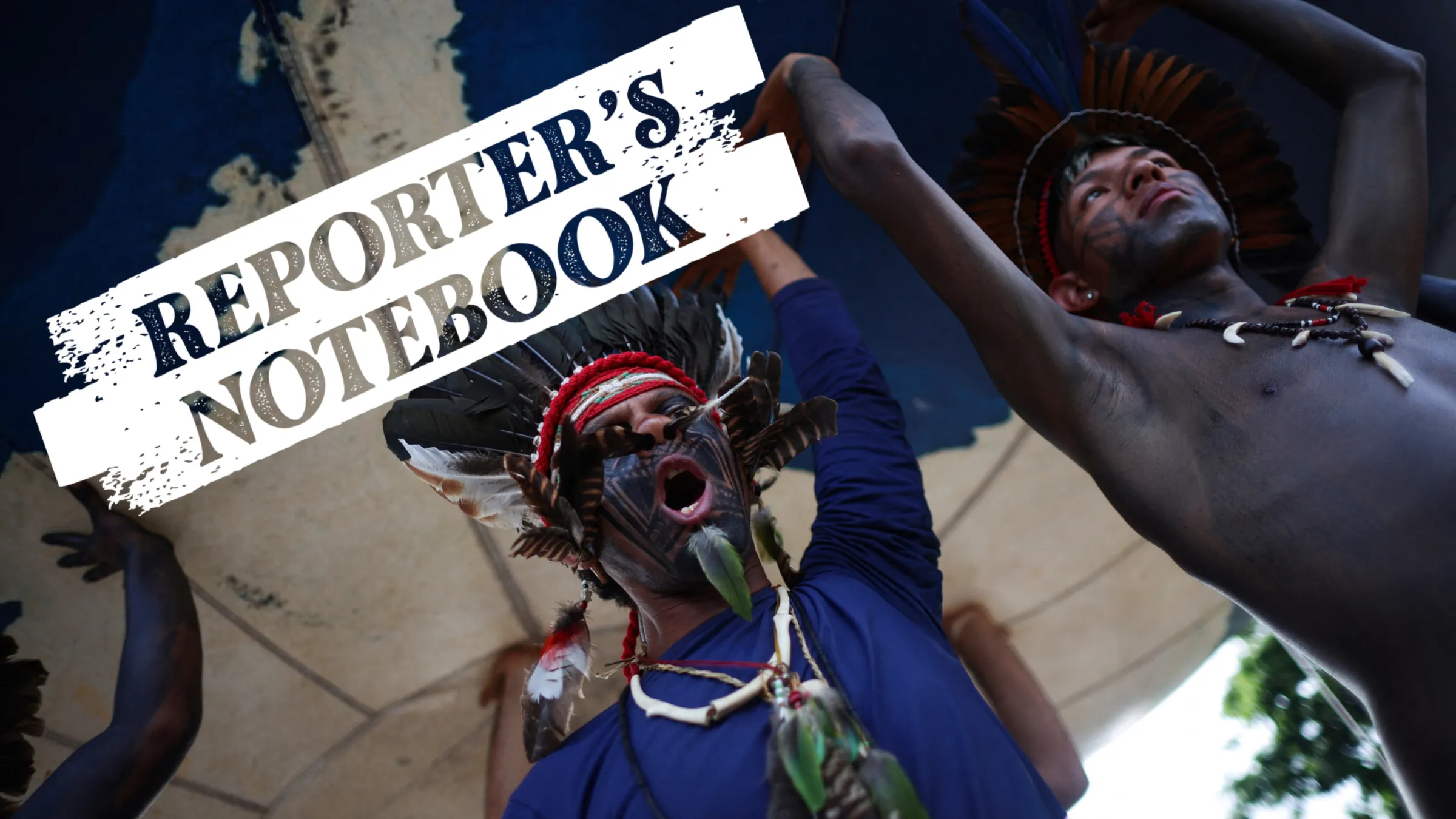

Indigenous cash

There is a particular need for money to trickle down to indigenous and local communities, whose land is home to much of the world's remaining intact nature - and who are widely credited as its most effective guardians.

"We need to invest in the people who are committed to protecting their territories, their resources, even at the cost of their own lives," said Jennifer Tauli Corpuz, a member of the International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity.

Colombian President Gustavo Petro said on Monday he would spend $200 million annually for 20 years - and look for additional international backing - to set up a fund to pay farmers and others to provide environmental services by protecting forests instead of clearing them.

One major obstacle to such efforts is that the value of storing carbon remains too low in an economic system that largely does not penalise climate polluters nor put an economic value on services such as clean air and reliable rainfall.

A price of at least $30-$50 per tonne of carbon stored is needed "to provide the incentives, means and predictability" for countries to invest in protecting forests, according to a U.N. Environment Programme report released this week.

Prices in most carbon markets today are far below that.

"We don't have clear signals from the market about what nature is valued at," said Monica Medina, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs.

An assessment last month of global efforts to halt deforestation by 2030 showed they are not on track, with forest losses declining - but too slowly.

Palau President Surangel Whipps Jr., whose South Pacific island nation recently made its own "30x30" pledge, said nature - and climate - protection is an urgent priority.

"We’re all seeing the impact of climate change on our homelands and our lives daily. What more, if we don’t take action today?" he asked.

(Reporting by Laurie Goering @lauriegoering; editing by Megan Rowling.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Adaptation

- Climate policy

- Forests

- Biodiversity

- Climate solutions