Trees, tech and people help Mozambican park reverse nature losses

What’s the context?

Mozambique's Gorongosa National Park is merging science with human-rights conservation to take on global warming

For over two years, park warden Pedro Muagura drove up a dirt road every month to Mozambique's conflict-ridden Mount Gorongosa to secretly monitor a daring experiment to reforest the mountain's parched land.

Equipped with coffee seedlings his mother gave him, he began planting, surrounding the cash crop with fast-growing indigenous trees he hoped would shield it and in time restore the mountain's forests.

Park warden Pedro Muagura stands beneath trees at Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique, May 30, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Park warden Pedro Muagura stands beneath trees at Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique, May 30, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Only once his first crop of green coffee beans began turning cherry red in 2011 did he reveal his plan, aligned with Gorongosa National Park's ethos of people-centred conservation: Give people a reason to protect forests and they will.

"People used to say 'the forest is for the future' - but here the forest is for now," said Muagura, seated beneath trees at the national park, just southeast of the 1,800-metre (6,000-foot) mountain where his planting began.

Last year, communities around Gorongosa planted more than 260,000 coffee trees and 20,000 indigenous trees, with their most recent harvest yielding 16 tonnes of green coffee from more than 800 small-scale farmers, 40% of whom are women.

Freshly-picked coffee beans dry in the sun on Mount Gorongosa in Mozambique, May 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Freshly-picked coffee beans dry in the sun on Mount Gorongosa in Mozambique, May 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

The park's own operations employ a total of 1,500 mostly local people, in jobs varying from maintenance and guiding to research, making it one of the biggest employers in Sofala province, in central Mozambique.

Among other tasks, the workers build schools and hospitals for local communities, help them to harvest honey, plant cashews - another cash crop - and train former wildlife poachers to become rangers.

The work to simultaneously protect nature and keep the local economy humming stems from the park's unusual conservation vision, which melds nature conservation, tech innovation and scientific research with community education and job creation.

Around the world, such ambitious efforts - at least successful ones - remain a rarity, particularly as international funding for nature protection falls short.

From the recent evictions of Maasai people from nature reserves in Tanzania to the battles of indigenous Batwa people in Uganda and San in Namibia to hold onto their land, local communities have often suffered at the hands of conservation projects that put animals before people.

Vanishing nature, threatened people

Julius Samuel, who helps lead a coffee-growing project on Mount Gorongosa, Mozambique, stands beneath indigenous trees growing over the tree nursery on the mountain, May 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Julius Samuel, who helps lead a coffee-growing project on Mount Gorongosa, Mozambique, stands beneath indigenous trees growing over the tree nursery on the mountain, May 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

In July 2021, the United Nations released a draft biodiversity framework calling for 30% of the earth's land and sea to be conserved by 2030, a so-called "30 by 30" plan.

Backers say that is crucial to protect nature and the essential services it provides, from producing oxygen and key ingredients for medicines to regulating rainfall and absorbing climate-changing carbon dioxide.

But the plan has drawn ire from human right groups who say it could lead to mass evictions of indigenous people.

A view of green hills on Mount Gorongosa, Mozambique, where agroforestry and reforestation projects are being carried out, May 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

A view of green hills on Mount Gorongosa, Mozambique, where agroforestry and reforestation projects are being carried out, May 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

"From its inception... conservation has understood humans as a threat to biodiversity and sought to exclude them from protected areas," said Chris Kidd, policy advisor for the human rights charity Forest Peoples Programme.

Gorongosa National Park, however, represents a shift away from the "fortress conservation" mentality that involves barricading communities away from nature reserves and the tourists who visit them.

Earning community trust has not always been easy. Early efforts to restore the park sparked fears in surrounding communities of evictions, academic research showed. But the fears were not realised.

Gabriela Curtiz, Gorongosa National Park’s first female guide, stands near the park’s head office in Mozambique, May 23, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Gabriela Curtiz, Gorongosa National Park’s first female guide, stands near the park’s head office in Mozambique, May 23, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

"We are a human rights national park," said 23-year-old Gabriela Curtiz, the reserve's first female guide, born in the nearby town of Vila Gorongosa.

Gorongosa's leaders believe the park - set in one of the world's poorest countries and faced with mounting climate shocks, including repeated cyclones - can be a conservation blueprint for other threatened parts of the world too.

"If you want to be successful, you can't create an island. The land must belong to the people," said Angelo Levi, director of conservation at Gorongosa.

Turnaround

Gorongosa National Park was not always a success story.

Sixteen years of civil war in Mozambique in the late 20th century killed an estimated 1 million people before a peace accord ended the fighting in 1992. Gorongosa, one of the conflict sites, was left void of almost all wildlife.

Population growth and urbanisation in surrounding communities threatened the remaining biodiversity as indigenous forests were cut down for firewood, agriculture and housing. Poaching remained a concern.

American conservationist and philanthropist Greg Carr looks at a map of Gorongosa National Park on the floor of a chalet in the Mozambican park, May 22, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

American conservationist and philanthropist Greg Carr looks at a map of Gorongosa National Park on the floor of a chalet in the Mozambican park, May 22, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

In 2004, American philanthropist Greg Carr visited the site, acting on an invitation from the Mozambican government, and decided to put millions of dollars into trying to do conservation differently.

He said he was inspired by Nelson Mandela's Peace Parks Foundation, an organisation that aims to use conservation and national parks to link and rebuild countries previously decimated by conflict.

"I'm just a person that came along and joined a movement that was already happening," he noted.

After seeing the park's largely empty grasslands, riverine forests and savanna woodlands, Carr said he understood its potential for restoration.

"This is a spectacular park and it could become one of the best in Africa with some assistance," he wrote in the park's guest book at the time.

In 2008 he signed a public-private partnership with the government to facilitate the restoration and protection of the park, covering nearly one million acres (405,000 hectares) of land. The contract was later extended to run until 2043.

Living classroom

Since the inception of the project more than 250 scientists from more than 40 universities and other research institutions have worked in the park.

It offers one of the first conservation masters' degrees taught fully within a national park.

For many scientists - and local people alike - the reserve has become a living classroom, and education starts young.

"What harms biodiversity?" Muagura, a former teacher, asked a room full of the students visiting Gorongosa to celebrate the International Day for Biological Diversity and enjoy a safari drive.

Little hands shot up, one by one. "Deforestation," said one child. "Poaching," said another.

On a near-weekly basis, children from surrounding communities are brought into the park to learn about conservation, go on game drives and meet animals such as pangolins rescued from traffickers.

Education for local people is crucial so they can better understand what is being protected and why, park staff say.

A student smiles while examining a seed handed to him during a lesson about biodiversity while on a visit to Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique, May 22, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

A student smiles while examining a seed handed to him during a lesson about biodiversity while on a visit to Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique, May 22, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

In the reserve's forested areas, scientists work plotting digital maps, analysing fossils, labelling insects and photographing bats in research laboratories close to nature.

A newly-built 'ambient lab' - with mesh walls for ventilation - allows researchers to study the impact of changing temperatures and water availability on plants and insects, providing clues as to what the future might hold as climate shocks become more common.

Using a locally designed biodiversity database, researchers have collected and documented thousands of species, including insects and frogs, and used a barcode system to allow researchers to quickly scan and identify the many species in the park's collection.

They aim to build a complete 'Map of Life' inventory of biological diversity in the park - a first for any protected area in Africa.

A Gorongosa pygmy chameleon (Rhampholeon gorongosae), balances on a finger in Mount Gorongosa, Mozambique, July 21, 2015. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Handout via Piotr Naskrecki

A Gorongosa pygmy chameleon (Rhampholeon gorongosae), balances on a finger in Mount Gorongosa, Mozambique, July 21, 2015. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Handout via Piotr Naskrecki

Scientists and researchers have documented over 1,500 species of plants in the park and found about 100 new-to-science insects, bats and frogs.

An ultra-sonic recorder collects bats' acoustic signatures in the field, helping scientists identify them.

Many animals - some not seen for the last century - have been rediscovered, including a rare crustacean and horseshoe bat.

"Each species that we add to the list is proof that what we are doing is working," said Piotr Naskrecki, associate director of the national park's science labs.

Piotr Naskrecki, associate director of Gorongosa National Park’s science labs, stands alongside pinned insects used for research at the Mozambique park, May 22, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Piotr Naskrecki, associate director of Gorongosa National Park’s science labs, stands alongside pinned insects used for research at the Mozambique park, May 22, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Understanding the reserve's ancient history is also a big focus of research.

One Mozambican student, Jacinto Mathe, is completing his doctorate degree in palaeontology at the University of Oxford - but comes back to the park to collect data.

"If we compare ancient changes to current climatic changes, we can better predict what the future will bring for biodiversity," said Mathe, 29, picking up bones and fossils lining the shelves of the park's palaeontology lab.

Storms and stoves

In the face of worsening droughts, floods and extreme heat in Mozambique - staff watched dead birds fall from the sky when temperatures soared in late 2019 - Gorongosa Park also has become a real-time experiment in dealing with climate change impacts.

Cyclone Idai in 2019 brought winds and incessant rain that killed hundreds of people, displaced thousands more and caused hundreds of millions of dollars in damage in southern African countries including Mozambique, with its long Indian Ocean coastline.

Another three tropical cyclones have hit since.

In the wake of Idai, the park's rangers and scientists morphed into ad-hoc humanitarian workers, using park-funded helicopters to reach flood-hit families stranded on rooftops or drop food for the hungry.

Members of Gorongosa National Park’s health and natural resource committee stand around a table of locally sourced food as part of a project to help improve nutrition in the buffer zone of the Mozambican park, May 24, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Members of Gorongosa National Park’s health and natural resource committee stand around a table of locally sourced food as part of a project to help improve nutrition in the buffer zone of the Mozambican park, May 24, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

All activity at the park was halted for five months to support about 50,000 flood survivors.

The park's "sponginess" - a term used to describe how trees, plants and wetlands help absorb excess rainwater - also saved lives.

Park managers estimate that the reserve absorbed up to 800,000 Olympic swimming pools of water during the deluge, preventing worse flooding nearby.

"Beira city was devastated compared to the villages around the park," said Eva Bernardo, 30, a member of a local committee working with the park to tackle poaching and deforestation through workshops, patrols and tree planting.

Tropical deforestation contributes about 10% of all human-created emissions driving global warming, according to the United Nations' anti-desertification agency.

A view of a waterfall on Mount Gorongosa, near a coffee plantation on the mountain in Mozambique, May 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

A view of a waterfall on Mount Gorongosa, near a coffee plantation on the mountain in Mozambique, May 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

That makes finding ways to curb it crucial both to protect the climate and nature.

Near Gorongosa, about 10,000 eco-friendly cookstoves have been donated to communities near the park to reduce the amount of firewood they need to cut to cook meals.

"It is not easy - but without the development of people, we cannot protect nature," said Elisa Langa, the park's director of human development, who leads projects tackling an array of social issues, including child marriage.

Tech and people

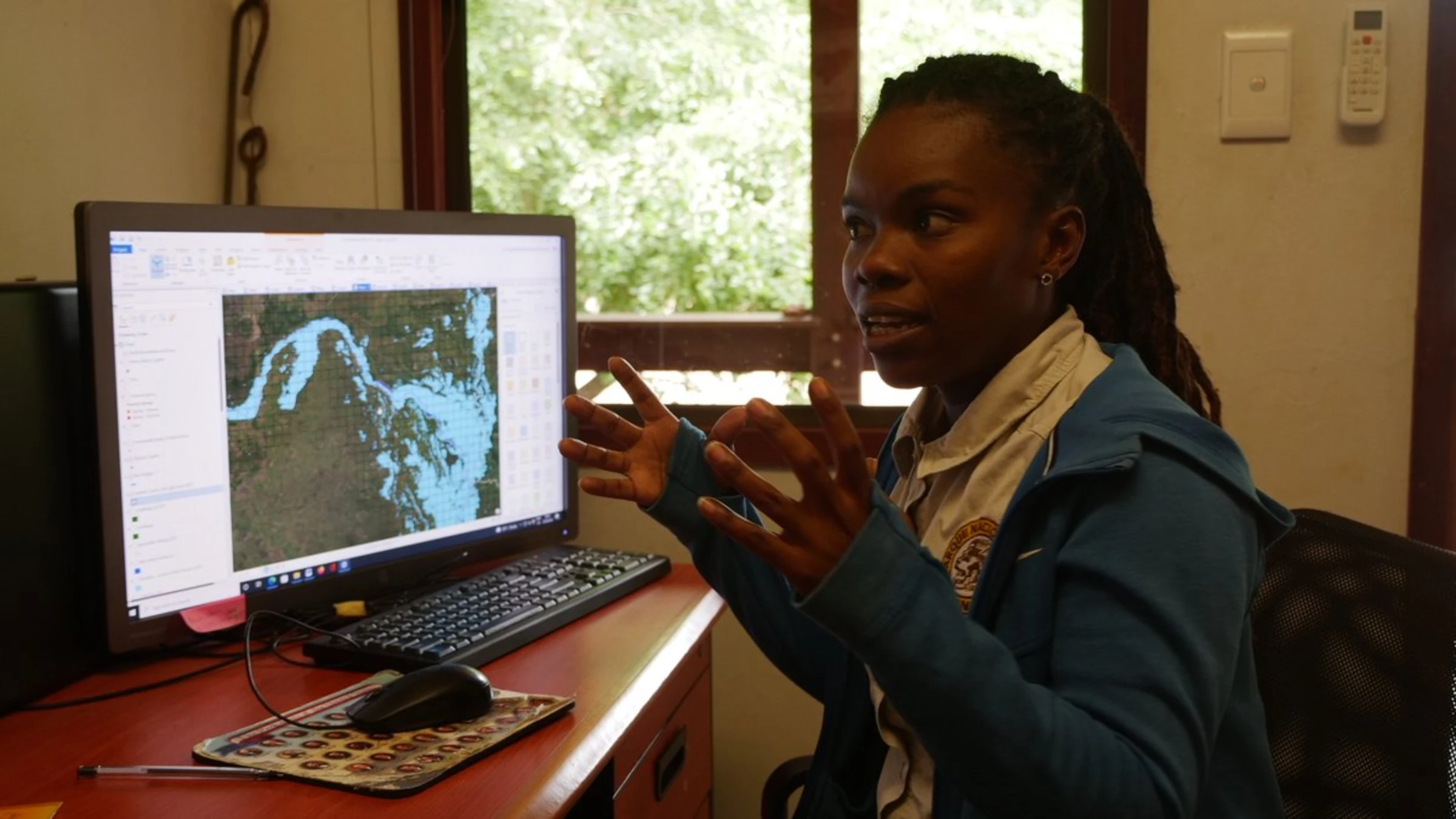

Margardia Victor, a Geographic Information System (GIS) expert working at Gorongosa National Park, shows how the reserve’s technology was used to map flood areas during Cyclone Idai, which slammed that area of Mozambique in 2019, May 23, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Margardia Victor, a Geographic Information System (GIS) expert working at Gorongosa National Park, shows how the reserve’s technology was used to map flood areas during Cyclone Idai, which slammed that area of Mozambique in 2019, May 23, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Near the park's famed pangolin rescue centre, where veterinarians tend to the world's most-poached animal, wildlife vet Mercia Angela monitors the movement of other threatened park species on a interactive digital dashboard.

"This technology makes our lives much easier," she said, demonstrating how she uses satellite communication services integrated through EarthRanger software to track collars placed on the park's most at-risk species including wild dogs, lions and elephants.

The system, installed in 2018, allows rangers to monitor animals' movements on a large screen from their offices.

Workers can set WhatsApp notifications to alert them when wildlife enter settlements or have stopped moving for long periods and might be in danger.

That allows them, for instance, to determine when to send rangers to check on an animal, or where to install beehives, which can help deter elephants intent on eating crops.

When elephants threaten a community's farms and safety, rangers sometimes resort to setting off fireworks and using flashlights and horns, called buzinas, to scare them away.

Wildlife veterinarian Mercia Angela and EarthRanger partnership manager Bruce Jones monitor the movement of threatened species on an interactive digital dashboard in Gorongosa National Park’s control room in Mozambique, May 25, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Wildlife veterinarian Mercia Angela and EarthRanger partnership manager Bruce Jones monitor the movement of threatened species on an interactive digital dashboard in Gorongosa National Park’s control room in Mozambique, May 25, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Partially in response to such stepped-up protections for communities, poaching has fallen by more than 80% since the public-private partnership was set up, said Marc Stalmans, the park's director of scientific services.

Despite the tech's success, rangers say technology alone is not the answer to improving conservation.

"We can roll out as much tech as we need, but the single best resource are the boots on the ground," said Jes Lefcourt, EarthRanger's senior director of conservation technology, from inside the Gorongosa control room.

Peace park

Mount Gorongosa is slowly turning green as its trees grow taller and locals report healthier soil and wildlife returning to the buffer zone around the reserve.

But ensuring ongoing conservation of the area as the local population grows - which can boost pressure for tree felling, farming and poaching - is a challenge.

"People need to eat, now," said Langa, the park's head of human development.

Community members walk towards a school funded by Gorongosa National Park in the reserve’s buffer zone in Mozambique, May 24, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Community members walk towards a school funded by Gorongosa National Park in the reserve’s buffer zone in Mozambique, May 24, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

As well, though fighting has largely ceased, conflict still flares occasionally between Mozambique's ruling Marxist Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO) and the anti-communist insurgent forces of the Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO).

The park was the site of a peace deal signing in 2019 which bought together the opposition groups, with both planting trees in the park as a peace gesture.

But even during periods of fighting between 2013 and 2018, women living near the town of Mount Gorongosa would sneak off when the guns quieted to water and weed the coffee bushes, keeping the project alive.

Now they are literally harvesting the fruits of their labour.

"We suffered a lot during the conflict," said farmer Imaculada Furanguene, taking a break from harvesting coffee beans on the 241-hectare (530-acre) plantation started with Muagura's secret planting experiment in 2009.

"But today I own a motorcycle, a sewing machine, have a house with iron sheets instead of mud and I send my children to school," she said.

Coffee farmers Imaculada Furanguene and Fatiange Paulino smile alongside drying red coffee beans on Mount Gorongosa in Mozambique, May 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Coffee farmers Imaculada Furanguene and Fatiange Paulino smile alongside drying red coffee beans on Mount Gorongosa in Mozambique, May 26, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

These are life-changing milestones in a country where 43% of people suffer from chronic malnutrition and nearly one in five girls are married before the age of 15, according to UNICEF, the U.N. children's agency.

Gorongosa park staff also facilitate "peace clubs" to help educate ex-combatants, their families and communities.

'Be respectful, be patient'

Since efforts to revive it began, the park has invested the equivalent of $30 million toward human and sustainable development projects for 200,000 people living in the reserve's buffer zone, its finance team said, with funding coming in from new donors beyond Carr.

Tourists visiting the park these days are encouraged to buy the coffee and honey produced by nearby communities, to plug money into a model backers hope will become self-sufficient in time.

Communities may also eventually benefit from a carbon credit scheme set to be rolled out, which would provide them with an income in exchange for protecting their indigenous forests, which absorb climate-changing carbon dioxide.

Young girls dance outside a classroom paid for by Gorongosa National Park in the buffer zone surrounding the park in Sofala province, Mozambique, May 24, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Young girls dance outside a classroom paid for by Gorongosa National Park in the buffer zone surrounding the park in Sofala province, Mozambique, May 24, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

One of Gorongosa National Park's greatest strengths, said Carr, its main funder, is that 98% of its staff are Mozambican and can operate in local languages and cultures in a way foreigners could not.

He said one of the most important lessons he has learned at Gorongosa is to "be respectful, be patient, let (locals) make the decisions" to try to ensure both biodiversity and people benefit in the long run.

"I think I could die today and this would all go forward," he said

A bird flies over a lake as the sun sets and turns the water and sky orange in Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique, May 30, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

A bird flies over a lake as the sun sets and turns the water and sky orange in Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique, May 30, 2022. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Moving at a patient pace can be a challenge for other conservation restoration initiatives, however, with many facing uncertain funding or pressure to show progress within the space of short-term grants.

Muagura, now famous locally for his tree planting and forestry expertise, says more successes like Gorongosa's are urgently needed.

"Protected areas are a way of giving the world a chance to minimise climate change," he noted. "These are our environmental banks."

Reporting: Kim Harrisberg

Text editing: Laurie Goering

Photography: Kim Harrisberg, with handout photos courtesy of Piotr Naskrecki

Videography: Kim Harrisberg

Graphics: Diana Baptista

Video editing: Jacob Templin

Producer: Amber Milne

Tags

- Clean power

- Climate policy

- Forests

- Green jobs

- Climate solutions