Lula's election promises rankle in Bolsonaro Amazon stronghold

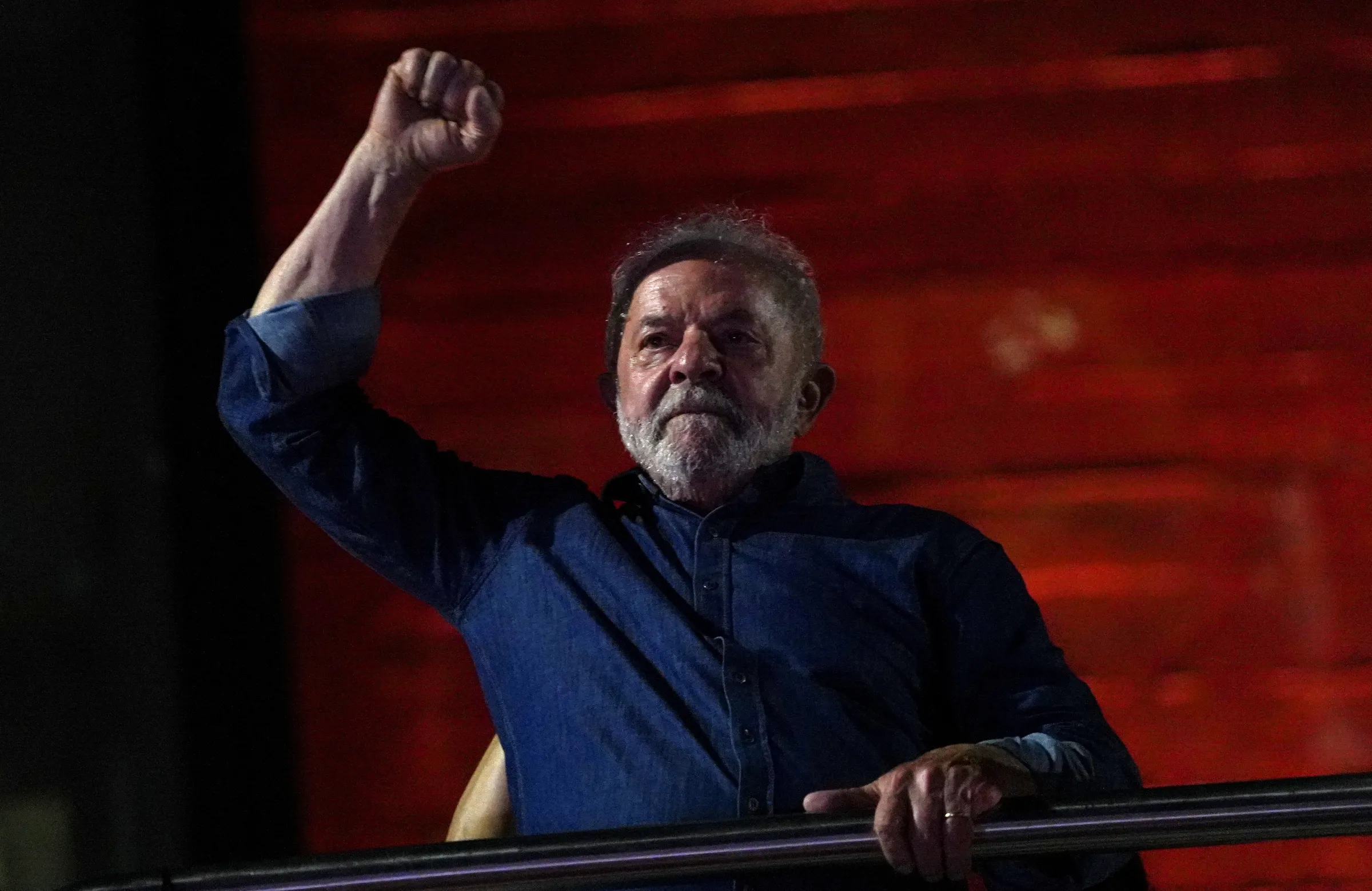

Brazil's former President and presidential candidate Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva reacts at an election night gathering on the day of the Brazilian presidential election run-off, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, October 30, 2022. REUTERS/Mariana Greif

What’s the context?

Lula has won Brazil's presidency, but his pledges to rein in forest loss and illegal mining still face tough political opposition

- Lula has pledged to rein in deforestation and illegal mining

- Promises face strong political opposition in northern Amazonia

- Bolsonaro strongholds to be challenge for Brazil's new president

BOA VISTA, Brazil - Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2005 oversaw the formal creation of the Raposa Serra do Sul indigenous territory in the northern Amazon state of Roraima, in his first term as Brazil's president.

The territory - which is home to five separate indigenous groups - is the biggest chunk of indigenous land in Brazil, at 1.75 million hectares (4.32 million acres), and a key legacy of "Lula" - as he is widely known - and his time in office.

The declaration of the territory - which, along with 31 other indigenous-held areas, adds up to 46% of Roraima's land - was strongly opposed by many of the state's voters, farmers and politicians, especially those forced to leave newly declared indigenous zones.

Today the political leaders of Roraima - many strong backers of President Jair Bolsonaro, who has encouraged farm, ranching and mining expansion in protected areas of the Amazon - are set to be a major thorn in Lula's side when he takes office in January, after winning a close election runoff with Bolsonaro on Sunday.

In declaring the reserve in 2005, "Lula committed the greatest crime in Brazil's recent history. It was a fraud," said Jailson Mesquita, who over his career has served as an assistant to several conservative politicians in Boa Vista, the capital of Roraima state, which borders Venezuela and Guyana.

Mesquita is the face of "Garimpo é Legal" - which translates as "Small-Scale Mining is Legal" - a movement he says has 2,000 members in Roraima state alone, and that has sprung up in the region as a growing number of small-scale miners prospect for gold, tin and other minerals, mainly illegally on indigenous land.

The mining process, in which heavy machinery is used to blast away soil and the beds of Amazon rivers, has caused widespread damage, deforestation and releases of toxic mercury - used to process gold - in the region's waterways.

The movement of miners into indigenous territories also has helped spread diseases, mercury poisoning and rising violence on indigenous land, indigenous groups say.

Lula has promised to rein in deforestation and illegal mining as Brazil's new president. But tough political opposition in areas where it is happening, as well as the difficulty of policing vast areas, could make fulfilling his promises a challenge, analysts say.

Besides miners, "agribusiness has been clearly adopting an anti-Lula stance," said Roberto Ramos, a social sciences professor at Roraima Federal University.

Destruction of Amazon forest has soared under Bolsonaro's administration, largely as lucrative cattle ranches and soy farming expand - often illegally - in forested areas.

In the second round of Brazilian elections, on Sunday, Roraima returned the worst results for Lula: Just 24% of people voted for him, compared to 76% for Bolsonaro.

The only municipality in Roraima where Lula came out on top was Uiramutã, which sits entirely inside the Raposa Serra do Sol territory.

But nationally, Lula took 51% of the vote, with Bolsonaro at 49% - though Bolsonaro had yet to concede the race on Monday morning.

During his campaign, Lula vowed to achieve net-zero deforestation in Brazil, with no more forest lost than can be replanted, and to shore up environmental protections weakened under Bolsonaro and eradicate rampant illegal mining in indigenous territories.

Mesquita has called that last goal "treason against the homeland" and alleged, without evidence, that it is part of a shadowy international effort to protect Brazil's resources so multinationals can extract them in the future.

Yanomami territory

Roraima, along with neighboring Amazonas state, is home to the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, where illegal small-scaling mining soared 3,350% between 2016 and 2020, according to data from MapBiomas, a network of research institutions and non-profits.

The Hutukara Yanomami Association, which represents the Yanomami people, has denounced a growing invasion of garimpeiros in its territory since 2019, when Bolsonaro and Roraima Governor Antonio Denarium, an ally of the president, came to power.

An April report estimates around 30,000 illegal miners are active in Yanomami territory, affecting over 270 communities on both sides of the border with Venezuela and leading to worsening violence as more miners and indigenous people meet.

In Boa Vista, a worker for Funai, Brazil's indigenous affairs agency, said many rivers in the territory are now contaminated with mercury, used in gold processing, making it difficult for indigenous communities to safely fish.

Malaria cases among Yanomami people have soared by more than 12 times since 2014 as illegal gold mining intensifies, health researchers said in April.

Hunting has also became harder, as animals flee mining disruption.

Mining town

Small-scale mining may be illegal in indigenous territories - but in Boa Vista it is not hard to find signs of it.

Parked by the Federal Police superintendent's Roraima office are more than a dozen pieces of mining-related equipment - from heavy trucks to small airplanes - seized by authorities from illegal miners.

There's also a helicopter painted in Brazil's national colors - green and gold - and used by one "garimpeiro" who ran for Congress this year as a form of advertising and protest.

He was not elected.

Equipment used in illegal mining - generators, motors, hoses and metal detectors - can be easily bought in the shops in Ville Roy Avenue, one of Boa Vista's main streets.

Edinho Macuxi, coordinator from the Indigenous Roraima Council (CIR), said several airstrips largely dedicated to gold smuggling sit just outside the city.

Under Bolsonaro, "we have a government policy which effectively feeds this spirit of invasion" of indigenous territories, he charged, adding that it is growing in Raposa Serra do Sol.

Near the city center, in Rua do Ouro ("Gold Street"), and in many other shops around the city, mined gold is bought and sold in jewelry shops.

And in the city's central square, in front of the state government office, stands a monumental statue of an old-fashioned garimpeiro, holding a sieve.

The overwhelming majority of the assembly's members, as well as Roraima's governor, are backers of mining.

Last year, the state assembly approved a bill simplifying environmental licensing for small-scale mining and allowing the use of mercury to separate gold from other substances.

At the time, Denarium promised the changes would "take mining out of illegality", benefit 50,000 people and generate jobs, income and taxes. Only two politicians voted against the bill.

In June, the assembly passed a second bill prohibiting the destruction of illegal mining machinery seized by state authorities.

Both laws were approved by the governor, but were later overturned by Brazil's Supreme Court.

Disputed land

Joenia Wapichana, the first indigenous woman elected to Congress, in 2018, traces strong support for mining and agribusiness expansion in Roraima to Brazil's former military dictatorship from 1964 to 1985, when settlers were promised access to the state's vast lands.

"Most of these people wanted to colonize the Amazon, to take possession of the land and open it to exploitation", said Wapichana, who lost her seat in this month's elections.

In spite of the state's pro-mining stance, she is optimistic that a Lula administration could end illegal mining in indigenous territories, noting how the creation of Raposa Serra do Sol was pushed through after over three decades of waiting, despite local objections.

One of the dictatorship-era immigrants to Roraima is Ermilo Paludo, who left his farm in southern Brazil and moved north in the 1970s.

With his family, he bought land from the government and occupied other pubic land, in order to request ownership be transferred to him.

For him, the battles over policy feel personal. In 1992, after democracy was restored in Brazil, he and his family's original farms in Roraima were reclaimed by the government and recognized as part of the Yanomami territory.

In accordance with Brazilian law, the government did not pay for the land, only for the infrastructure built, something he sees as deeply unfair.

"Can you imagine losing a 10 million (reais) property and receiving only 1 million in exchange?" he asked.

On his primary current 5,400 hectare (13,300 acre) farm, which he bought from the government and private owners a decade ago, he cultivates soy, sorghum and corn and runs 5,000 head of cattle.

He says he is not against his indigenous neighbors, but thinks that indigenous territories, forest conservation units and other legal limits on deforestation leave very little of Roraima's land available to farmers, who need space to thrive.

What farmers want most, he said, "is to be able to produce legally and predictably".

A Bolsonaro voter, he backs Denarium's efforts to transfer state-owned land to settlers who have occupied it since 2017 or earlier.

Last week, Denarium was busy doing just that, with a pile of newly signed land titles in his office in Boa Vista.

He hopes the federal government legalizes mining in indigenous territories as well.

"What good is it for the indigenous to have 10 million hectares of land and live in deprivation?" he asked, suggesting legalized mining could benefit them as well as miners.

Government data shows Roraima's deforestation rate reached a 30-year high in 2019, the year Denarium came to office and began signing land titles.

Since then, it has been the Amazonian state with the sharpest increase in deforestation from 2019-2021, compared with the previous three years, according to IPAM Amazônia, a non-profit sustainable development organization.

Denarium said he is not worried that many of his positions stand in opposition to Lula's.

"You have in Congress over 500 politicians. They are the ones who will make the laws", he said.

(Reporting by Andre Cabette Fabio; Editing by Laurie Goering.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Climate policy

- Loss and damage

- Forests