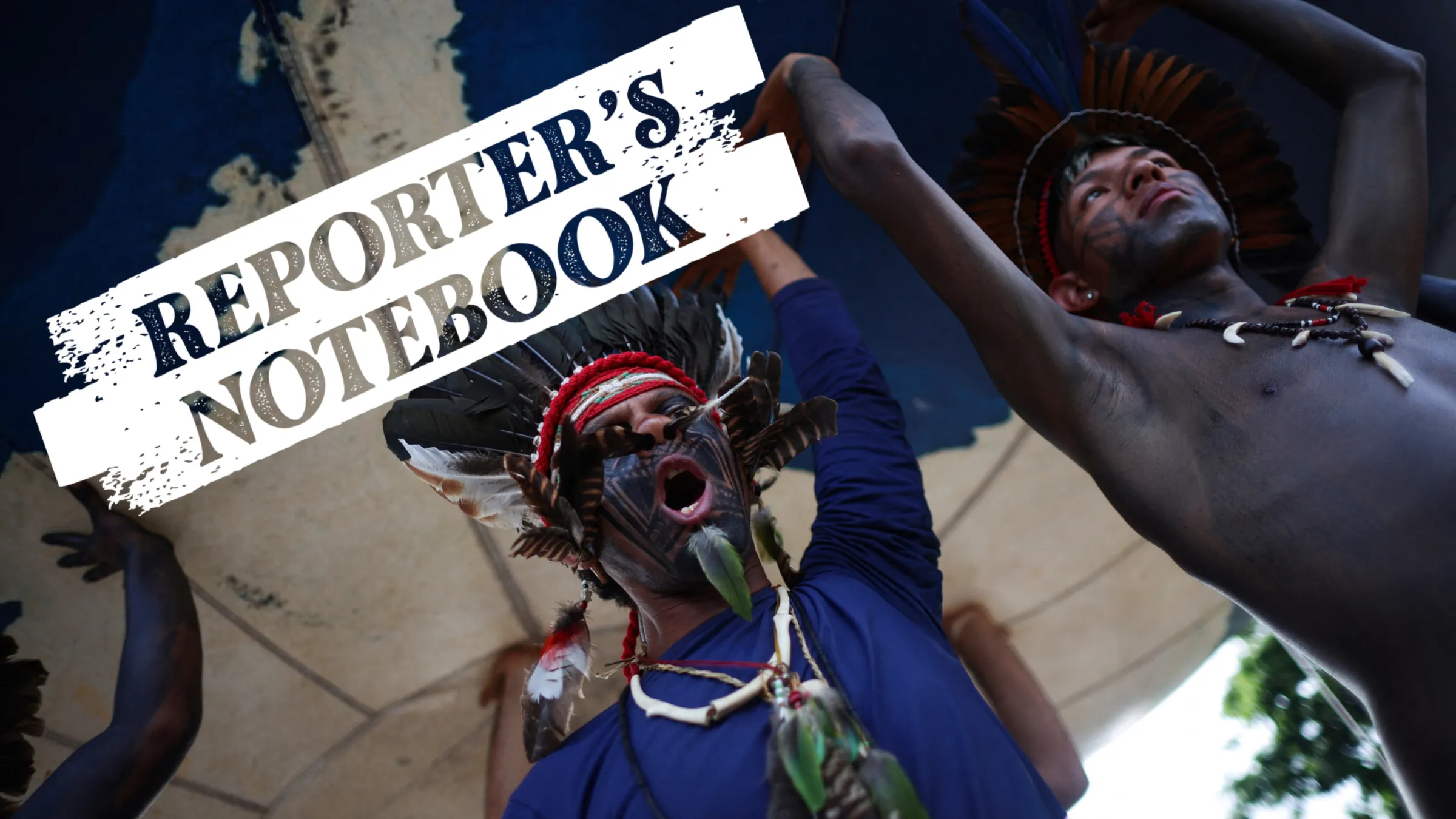

Indigenous stewardship is the ignored climate solution

A child climbs a tree in a village in Kaxarari Indigenous land, in Porto Velho, Rondonia State, Brazil August 11, 2024. REUTERS/Adriano Machado

Securing Indigenous land tenure offers huge climate returns at a fraction of the cost of large-scale forest protection programs.

Robert Muggah is the co-founder of Igarape Institute, a Brazilian think-think.

As the world stumbles toward climate tipping points, a growing body of scientific evidence suggests that among the most powerful defenders of nature are not satellites or carbon markets, but people - Indigenous peoples.

From the rainforests of the Amazon to the boreal forests of Canada, Indigenous stewardship may be one of the most high-impact and cost-effective strategies to mitigate climate change, preserve biodiversity, and disrupt environmental crimes.

Indigenous peoples occupy, use, or manage over a quarter of the Earth's surface, including many of its most ecologically intact regions. These territories often overlap with areas of high carbon density and biodiversity richness.

Where land rights are formally recognized, deforestation rates are consistently two to three times lower than in surrounding lands. In Brazil, for instance, forests inside demarcated Indigenous territories experience dramatically less forest loss than non-designated lands, a pattern echoed across Peru, Colombia, Mexico, and Canada.

According to a study by the FAO and FILAC, Indigenous and Tribal peoples in Latin America and the Caribbean manage nearly 36% of the region's intact forests. Between 2000 and 2012, forest carbon stocks in Indigenous territories remained stable, while those in other areas declined. The report also shows that recognizing land rights and supporting local forest governance is not only environmentally sound, it's economically prudent.

The cost of securing tenure is far lower than the billions spent each year on large-scale reforestation and protection schemes.

These forests are not simply left untouched, they are actively managed. As the Rainforest Foundation notes, Indigenous forest practices rooted in traditional ecological knowledge support sustainability and adaptation.

Community-based monitoring, rotational agriculture, and controlled burns reduce fire risk while supporting biodiversity. These systems are low-cost, flexible, and resilient, often functioning with minimal state support despite legal and physical threats.

In Canada, Indigenous leadership is central to the country's forest conservation strategy. According to Nature Canada, Indigenous-led restoration projects bring cultural values, territorial knowledge, and long-term ecological planning that technocratic approaches often overlook.

The Cree Nation's sustainable forestry model and the Haida Nation's stewardship of the Gwaii Haanas reserve are powerful examples of governance rooted in sovereignty delivering measurable environmental outcomes.

Scientific research supports these observations.

A peer-reviewed article in PNAS found that deforestation in Indigenous-managed protected areas across Bolivia, Brazil, and Colombia was significantly lower than in comparable areas not under Indigenous control. Legal recognition of collective tenure rights and support for local governance were key to these outcomes.

Underfunded, underprotected

Yet despite this overwhelming evidence, Indigenous communities remain underfunded and underprotected. In Brazil, less than 1% of climate finance directly reaches Indigenous-led projects. At the same time, illegal logging, mining, and land grabbing continue to encroach on Indigenous lands, often with impunity.

Since 2023, Brazil's Congress has advanced legislation, including the so-called "devastation bill," which weakens Indigenous consultation rights and opens the door to more lenient environmental licensing, moves that are both ethically questionable and economically shortsighted.

If the world is serious about achieving the Paris Agreement targets or halting biodiversity loss, this paradox must be addressed: the people best equipped to safeguard nature are often excluded from the decision-making table.

Rectifying this will take more than symbolic gestures. It requires legal land recognition, increased financing and technologies for Indigenous-led conservation, and the full integration of traditional knowledge into national and global climate frameworks.

There are signs of progress. Indigenous voices were more prominent than ever at COP26 and COP27. Brazil's upcoming COP30, to be hosted in the Amazonian city of Belém, presents a unique opportunity to make that visibility meaningful.

If international donors and national governments channel more funding directly to Indigenous communities and accelerate land tenure recognition, Brazil could emerge not just as a climate actor, but as a global model where nature and justice align.

For policymakers and investors focused on value for money, the case is clear. The return on investment for Indigenous stewardship is unmatched.

Indigenous territories store billions of tons of carbon, protect rich ecosystems at relatively low cost, and act as frontline defenses against environmental crime. In regions plagued by illegal mining, poaching, and logging, Indigenous patrols often provide the only effective enforcement presence.

None of this suggests that Indigenous peoples should be idealized or instrumentalized. They are not a monolith, and they face the same pressures of development, scarcity, and politics as any community.

But the evidence is unequivocal: where Indigenous rights, responsibilities, and resources are respected, ecosystems are more likely to endure. That makes Indigenous stewardship not just a moral obligation, but a strategic necessity.

In a world searching for scalable, equitable climate solutions, perhaps the most powerful thing governments can do is to give Indigenous peoples the tools and authority to continue doing what they have done for generations: take care of the land.

Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Context or the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Tags

- Indigenous communities

Go Deeper

Related

Latest on Context

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6