How anti-migrant hate speech is spreading online in South Africa

Sudanese refugee children who have fled the violence in Sudan's Darfur region, play a game on a mobile phone beside makeshift shelters, near the border between Sudan and Chad in Koufroun, Chad May 11, 2023. REUTERS/Zohra Bensemra

What’s the context?

Rights groups have shown through an online experiment that harmful content is easily approved for publishing by social media giants

Editor's note: contains offensive language

Social media platforms are approving xenophobic online ads and failing to take down other hate-filled content in South Africa, according to research published on Tuesday.

Social media firms are under scrutiny worldwide - from the United States to Kenya - for content moderation practices that rights groups say allow hate speech like racism and xenophobia to spread online.

In South Africa, U.N human rights experts have recently warned that the country is "on the precipice of explosive xenophobic violence".

Here's what you need to know about xenophobic hate speech spreading online in South Africa:

What did the South Africa research reveal?

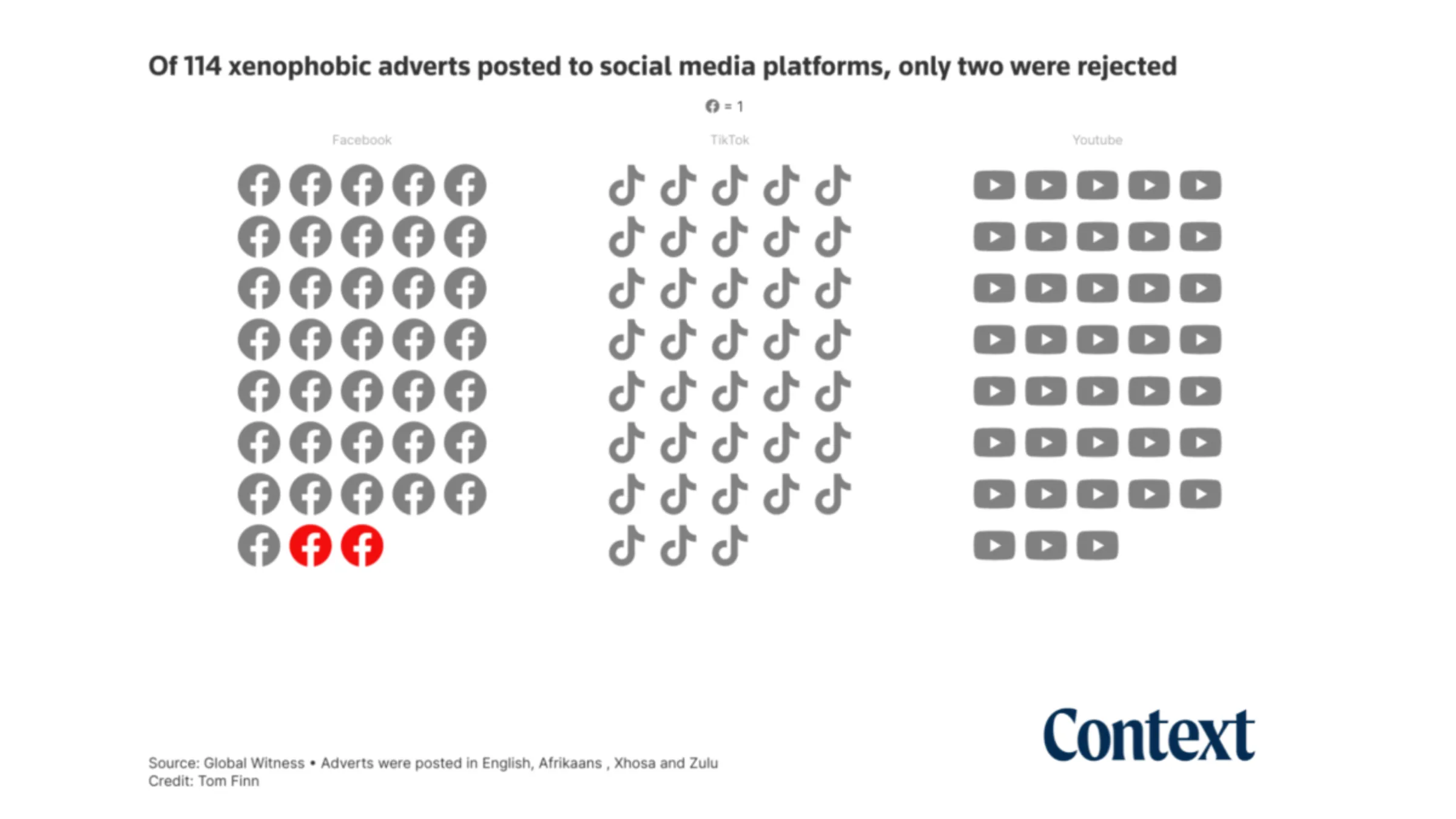

International rights group Global Witness and South African public interest law firm Legal Resources Centre (LRC) submitted 10 adverts to TikTok, Facebook and YouTube, translated into local Afrikaans, Zulu and Xhosa languages respectively.

The adverts incited violence towards foreigners, including calling on the police to "kill foreigners", and to use "force" against non-native South Africans who were referred to as a "disease".

Every advert was approved for publication by all three platforms, except for one which was rejected in English and Afrikaans, although it was approved in Xhosa and Zulu, revealed the study published on Tuesday.

Global Witness and LRC deleted the ads once they were approved for publication by the platforms, before they were publicly viewable.

"With rising tensions over the last couple of years and in the lead up to an important election year for South Africa in 2024, we are deeply concerned that social media platforms are neglecting their human rights responsibilities here," said Sherylle Dass, regional director at the Legal Resource Centre.

"We know from history that social media campaigns can result in real-world violence, so it is imperative that the platforms don't overlook South Africa and take proactive steps now to protect livelihoods and lives in future", she said in a statement.

In response to the findings, Meta and TikTok told Global Witness and LRC that the hate speech in the ads violates their polices, that their systems are not perfect and that ads go through several layers of verification.

A Meta spokesperson said that "both machines and people make mistakes. That's why ads can be reviewed multiple times, including once they go live."

Neither Google nor TikTok responded to Context requests for comment.

.

.

How common is online hate speech across South Africa?

Migrant rights groups say foreigners are often scapegoated for economic woes in a post-apartheid context.

Social media in South Africa is rife with hate speech towards foreign nationals, with hashtags such as #PutSouthAfricansFirst and #ZimbabweansMustFall frequently trending online.

For 47-year-old Zimbabwean domestic worker Nora, who asked to use a pseudonym, scrolling through Facebook, Twitter or WhatsApp often leads to a flurry of accusations towards migrants in the country.

She pointed to the end of 2022 when the permits of an estimated 180,000 Zimbabweans living in South Africa were set to expire and social media was a hotbed of xenophobic hate speech.

"At that time, but also since then, we are told online that the country is a mess because of us, that we need to go home, that we are not welcome," she said in a phone interview.

"It is scary to leave the house, and we never tell anyone we are not from here."

Where else have social media firms come under fire over content moderation?

Global Witness has run more than 10 similar tests in countries including Brazil, Ethiopia, Ireland, Kenya and Myanmar.

For each of these the rights group reported large gaps in social media companies' moderation methods, allowing harmful content to slip through undetected across platforms.

In 2022, a lawsuit by two Ethiopian researchers and Kenya's Katiba Institute rights group accused Meta of allowing violent posts to flourish on Facebook, inflaming civil conflict in Ethiopia.

The plaintiffs are demanding that Meta take emergency steps to demote violent content, increase moderation staffing in Nairobi, and create restitution funds of about $2 billion for global victims of the violence incited on Facebook. The case is ongoing.

In late 2021, a $150 billion class-action complaint was filed against Facebook by Rohingya refugees who argued that Facebook's failure to moderate its platform contributed to extreme violence against the Rohingya community in Myanmar.

Global Witness pointed out that in richer countries like the United States, content moderation has shown to be more robust, "suggesting an inequality at the heart of how such hate is addressed".

How have social media companies pledged to tackle online hate speech?

A day after the Rohingya lawsuit was filed, Meta said it would ban several accounts linked to the Myanmar military, and that it had built a new artificial intelligence system that can respond to new or evolving types of harmful content faster.

Facebook says a global team of over 15,000 reviewers work to constantly assess the content shared on their platform and that the same policies apply to all countries.

TikTok encourage users to report possible hate speech to them so they can "continuously review and improve" their policies, systems and products.

Google says it has removed more than 217,000 videos from YouTube that qualify as hate speech in its most recent data analysis.

(Reporting by Kim Harrisberg; Editing by Zoe Tabary)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Disinformation and misinformation

- Online radicalisation

- Content moderation

- Tech and inequality

- Tech regulation

- Social media

- Data rights