Home sweet home? U.S. caps gas to cut indoor pollution

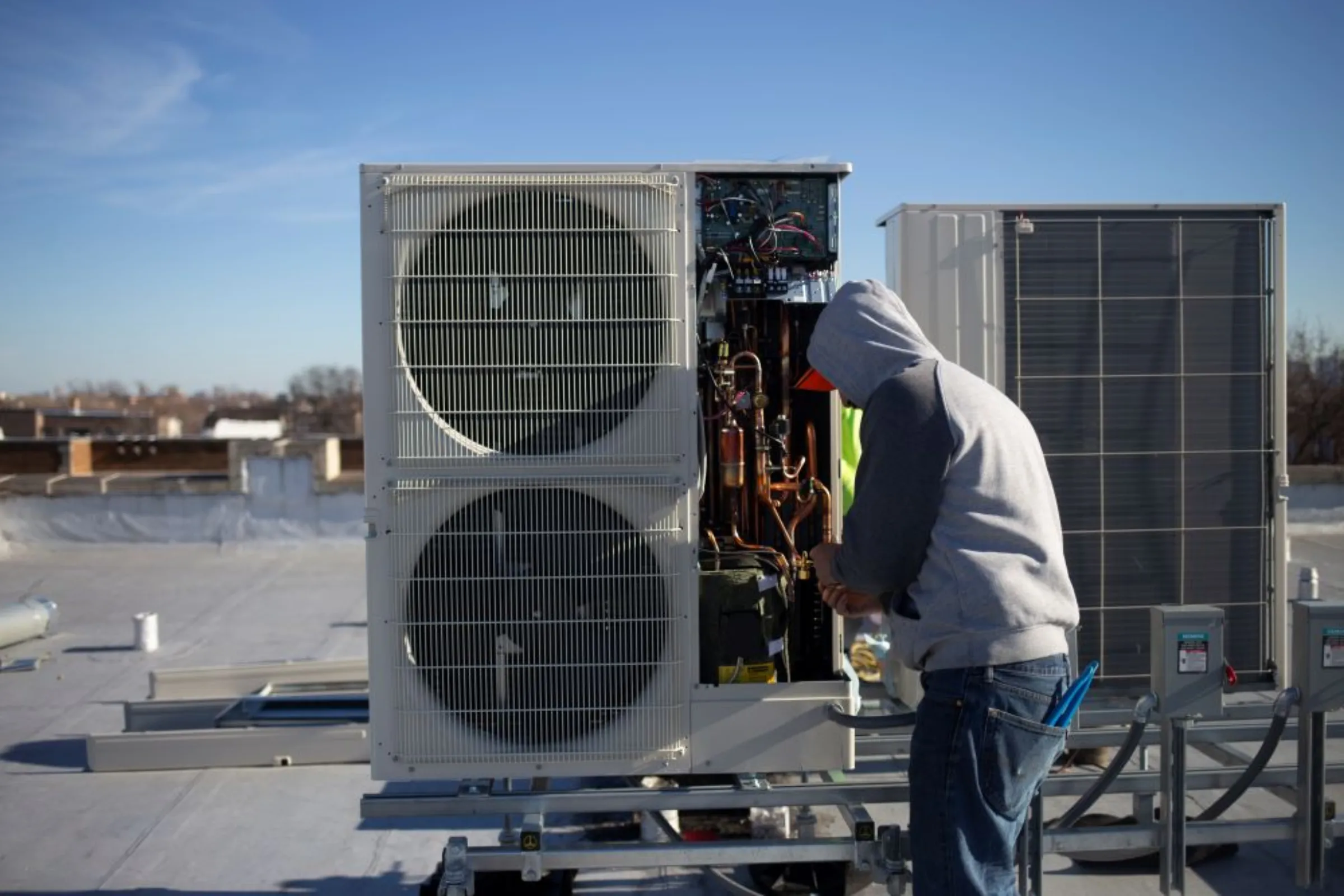

A worker installs a heat pump unit as part of a building electrification project in Chicago in spring 2022. Elevate/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

What’s the context?

New recognition of climate, health implications leads to federal investments

- Some 70 million U.S. buildings powered by fossil fuels

- A tenth of U.S. emissions come from heating and cooking

- States and cities push electric alternatives

WASHINGTON - Honnie Leinartas spends her days poking through the musty basements and drafty attics of the U.S. Midwest, taking a look at increasingly outdated and climate-polluting energy systems.

With many homes in the Chicago area built more than a century ago, there is a laundry list of potential problems lurking in every house she examines.

"I do assessments, which means going into the homes and looking at their existing heating and cooling systems. And their hot-water-heating systems – and cooking and clothes drying," Leinartas said.

Fuels burned in buildings make up about a 10th of all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, according to energy think tank RMI, with heating, hot water and cooking the main culprits.

So a new, nationwide push is underway to switch to cleaner appliances and energy sources in homes and commercial buildings, with pioneers like Leinartas at the forefront.

As lead engineer for electrification projects at Elevate, a nonprofit that helps weatherize and retrofit low-income housing, she helps Americans replace home appliances that burn fossil fuels with electric alternatives, such as heat pumps.

"There's so much more work that needs to be done," Leinartas said, estimating that some 350,000 homes need such upgrades in the Chicago region alone.

Refits are becoming increasingly common across the country.

Almost 100 local and state governments have endorsed moves to electrification, according to tracking by the Building Decarbonization Coalition.

Many now expect the trend to really take off, with tens of billions of federal dollars due to trickle down to the regions for mass weatherization and building electrification projects.

In December, the White House hosted an "electrification summit" - and triggered a powerful industry pushback.

The summit announced a suite of efforts to cut carbon from buildings and retrofit them with electrical appliances. It launched a coalition of more than 30 states and cities seeking to reduce climate-harming emissions.

This month, a regulator with the Consumer Product Safety Commission indicated his agency would study the impact of gas-burning cook stoves and consider a ban, sparking an outcry.

The American Gas Association has said banning fossil fuel gas would hurt communities, raising the price of housing while doing little to reduce overall U.S. emissions.

"The massive cost of complying with electrification mandates raises legitimate concerns about the amount of housing that can be built and maintained affordably under such a policy,” said Alex Rossello, who works for the Apartment and Office Building Association of Metropolitan Washington lobby group.

One legislator, Representative Ronny Jackson of Texas, warned in a tweet, "If the maniacs in the White House come for my stove, they can pry it from my cold dead hands."

Employees install an electric stove in a building in Chicago in 2021. Bickerdike Redevelopment Corporation/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

Employees install an electric stove in a building in Chicago in 2021. Bickerdike Redevelopment Corporation/Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation

A tenth of emissions

Advocates for change say the rising clamor on both sides reveals a new and growing awareness of the risks of inaction on global warming.

"There has been an awakening of public knowledge of the fact that natural gas is a fossil fuel that causes climate change and harms human health – and we have it inside our homes," said Mike Henchen, a principal on Colorado-based RMI's carbon-free buildings team.

The United States has about 70 million buildings that use fossil fuels, said Jenna Tatum, executive director of the Building Electrification Institute, and cities have been early movers on seeking alternatives.

"Most of them are initially motivated by their climate commitments, and looking at ways to drive down their emissions," Tatum said, noting that many cities have significant control over their building codes.

New federal money, approved last year, is expected to start flowing in coming months, accelerating the switch.

"It's a huge windfall, creating so much excitement and motivating many city and state staff to work on building electrification," Tatum said.

Yet with much of the money structured as tax incentives, she fears that funding could mostly flow to high-income homeowners and leapfrog poorer people, particularly renters.

Ensuring the benefits reach everyone has been a key priority for the city of Denver, which over the past year has been setting up one of the country's most expansive electrification programs.

By 2025, commercial and multifamily buildings that need a new furnace or water heater will be required to buy an electric option, as long as doing so is cost-effective, said Katrina Managan, director of buildings and homes for Denver.

Eventually the program aims to reduce energy consumption in buildings over 25,000 square feet by 30% by 2030, and 80% by the 2040, when the city also aims to have net-zero emissions, Managan said.

"We've designed the whole policy so it doesn't increase bills. The cost of operating should be very similar."

The same trend is taking place in Europe, where Russia's invasion of Ukraine has prompted a European Union-wide plan to double the sales of electric heat pumps.

Many countries have also banned standalone gas heating systems, said Jan Rosenow, director of European programs at the Regulatory Assistance Project, a Brussels-based NGO.

Heat pumps "had not been a technology that people knew much about, but that's changed. Now everybody is talking about the cost of heating," he said, predicting the focus would soon switch to the high environmental cost of cooking with gas as well.

Obstacles

In Denver, and in many parts of Europe, Rosenow and Managan said a lack of skilled installers was hampering electrification.

Housing design problems also can hinder progress, said Elevate's Leinartas, pointing to old wiring, electrical systems that could buckle under high demand, or exterior brick walls that can't be insulated.

"The biggest issue is the fact that I'm not sure the infrastructure is as ready as we need to go to scale," said Joy Aruguete, CEO of the Bickerdike Redevelopment Corporation, a Chicago nonprofit that manages affordable housing.

Over the past year, Bickerdike has been working with Elevate to retrofit a three-building complex, La Paz Place, and is hoping to do the same to two other projects.

But obstacles have cropped up.

Aruguete was unable to find electric hot-water heaters with enough capacity, while one project is facing a two-year wait for the utility to upgrade local transformers.

Still, La Paz Place residents now have new stoves, better insulation, air conditioning – and lower bills, Aruguete said.

"The residents are really happy. They love not having a gas bill, and even with the addition of air conditioning, their (electric) bills should be less than what they were."

The improvements also benefit the building's overall efficiency and operation, Aruguete said.

"That's good for us and for the residents."

(Reporting by Carey L. Biron. Edited by Lyndsay Griffiths and Laurie Goering)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Clean power

- Adaptation

- Fossil fuels

- Energy efficiency