At COP28, it’s time to transform the global financial architecture

A truck unloads tonnes of coal inside a warehouse in Tondo city, metro Manila January 11, 2016. REUTERS/Romeo Ranoco

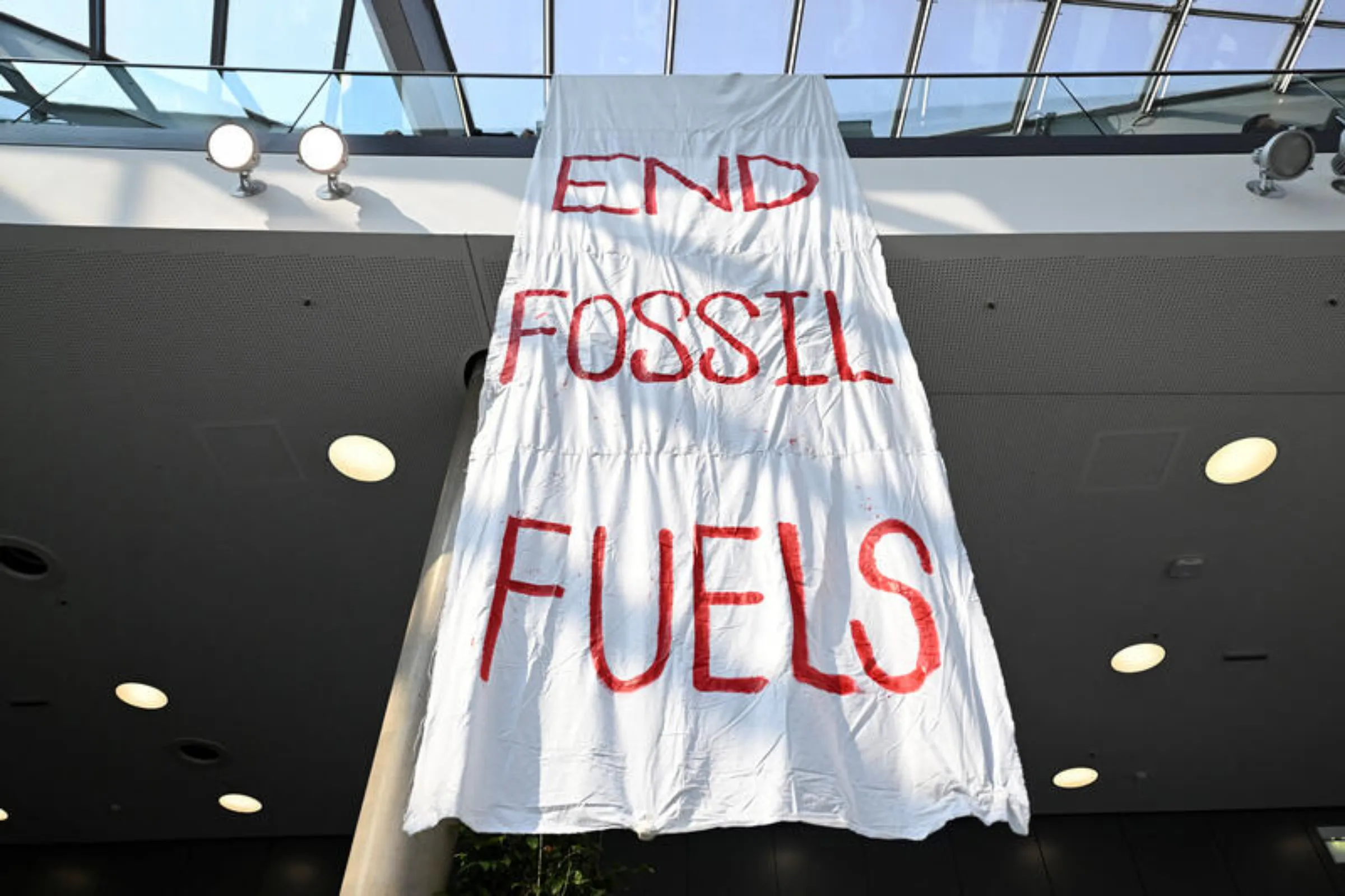

The global finance system is giving fossil fuels a lifeline, indebting vulnerable countries and delaying a just energy transition

Bronwen Tucker is the global public finance manager at Oil Change International, and Shereen Talaat is the director of the MenaFemMovement for Economic, Development and Ecological Justice.

In the wake of World War II, a new set of international economic rules and public financial institutions were created, with the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) at the centre.

This global financial architecture was set up with the aim of helping low-income and war-ravaged countries to rebuild and develop.

But this system had a fundamental flaw from the start, giving rich countries an outsized say in decision making. Eighty years on, the rules governing international monetary policy, trade, tax and debt are not just fuelling global inequality, but climate change too. They need a fundamental rethink.

In the last eight years, in spite of the increasingly visible accelerating impacts of climate change, and global consensus that we need to phase out fossil fuels, the World Bank has spent at least $17 billion funding oil, gas, and coal projects.

From the OECD to the World Trade Organization, the rest of the architecture is facilitating even larger fossil fuel subsidies.

The impacts of these handouts are clear. In 2023 alone, floods have devastated Kenya, Greece, Bulgaria,and Libya; tropical cyclones have torn through Madagascar, Mozambique and Malawi; and extreme heat, wildfires and droughts have spread across countless other countries.

At the heart of climate inaction is the fact that countries who are doing the least to cause climate change are experiencing the worst impacts. Responding to climate change and extreme weather has become unaffordable for low-income nations still reeling from Covid-19 and energy and food price hikes.

Many climate-vulnerable countries have looked to the IMF to finance the aid and adaptation necessary to protect their populations, but this has saddled them with huge debt, on which they pay exorbitant interest and surcharges.

On average, it costs African countries five times more to borrow money on international markets than rich countries, and low income countries overall spend 12 times more on debt repayments than addressing climate change.

To phase out fossil fuels and build a 100% renewable economy, the IEA estimates that low- income countries will need to spend $2.8 trillion a year on tackling climate change. That’s four times what is currently being spent. Trillions more are needed to address the climate impacts already locked in.

Given their historic responsibility for both climate change and our rigged financial system, it is rich country governments that must pay the bulk of these costs. But for decades, they have said they cannot afford to, proposing instead that small amounts of public finance can be used to attract private investment in what is needed.

But this approach has repeatedly failed to deliver the needed funds, and often added to unfair debt burdens.

The truth is, there is no shortage of public money to cover these costs. At COP28, we need wealthy country leaders to take some key first steps.

We need them to build on early progress to stop funding fossil fuels and put this money towards climate solutions instead. They must agree to reduce interest rates and cancel unfair debts.

And they must approve new sources of funding like levies on polluting industries, taxes on the super rich, and redistributing IMF reserve assets known as Special Drawing Rights (SDRs).

These measures will benefit all of us. Larger and fairer flows of international public funding for development and climate change will enable a global just energy transition, create jobs, and reduce the risk of conflict and forced migration.

It’s not just civil society asking for this. These calls have been voiced by Barbados’s Mia Mottley, Kenya’s William Ruto, Brazil’s Lula da Silva and Colombia’s Gustavo Petro, as well as leading academics such as Jaso Hickel and Mariana Mazucatto.

Together, our demands have created more momentum to change the global financial architecture than we have seen in decades.

Today is Finance Day at COP28. Wealthy country leaders have a huge opportunity to demonstrate political will and solidarity, and to increase momentum towards a democratic financial architecture fit to tackle the climate crisis.

Key moments to watch out for include the High Level Roundtable on Climate Finance and sessions on Climate Resilient Debt Clauses, SDRs and Innovation.

Climate-vulnerable countries need affordable and dependable finance, and international financial institutions need to transform to provide it.

With the world on track for a ‘hellish’ 3C of heating, this is the only way 1.5 will remain a possibility. Developing countries are on the frontline and the world owes them this.

Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Context or the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Tags

- Clean power

- Adaptation

- Climate finance

- Fossil fuels

- Net-zero

- Climate policy

- Climate inequality

- Energy access

Go Deeper

Latest on Context

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6