Can gas-guzzling Formula One ever go green?

Formula One F1 - Mexico City Grand Prix - Autodromo Hermanos Rodriguez, Mexico City, Mexico - October 29, 2023 Red Bull's Max Verstappen passes the chequered flag to win the Mexico City Grand Prix. REUTERS/Andres Stapff

What’s the context?

F1 says it wants to reach net zero by 2030 but can the sport be sustainable and help tackle climate change?

- F1 pledges net zero by 2030 and touts tech solutions

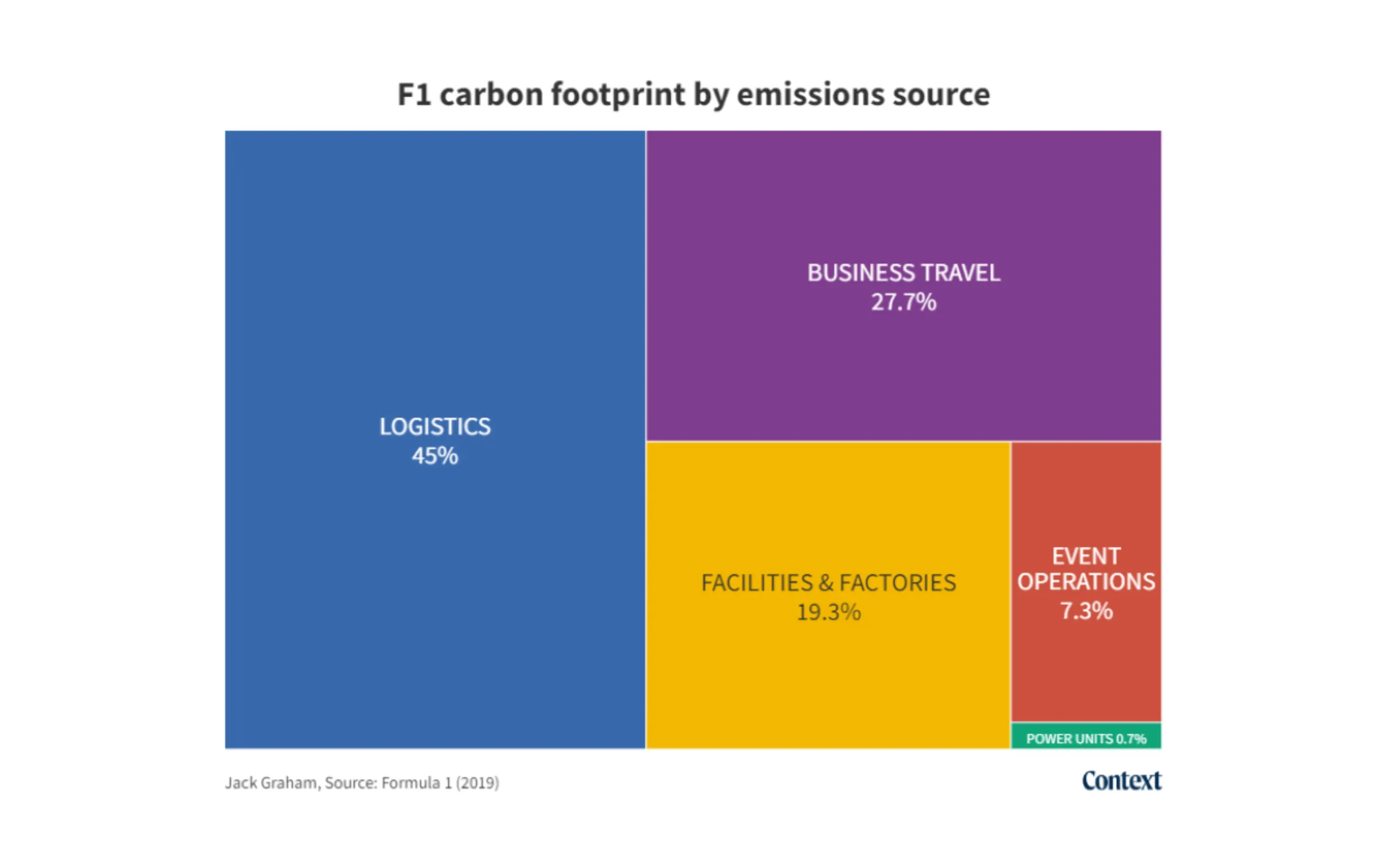

- Travel and logistics account for two-thirds of footprint

- Green groups question biofuels, offsets and calendar

LONDON - As Formula One's leading driver Max Verstappen racks up wins across the globe, scientists say the world is losing another race: to cut planet-heating greenhouse gases and avoid climate change's worst impacts.

Transport accounts for around a third of global emissions and no other sport is more associated with high emissions in this sector than F1, adored by fans as the pinnacle of motorsport.

Four-times world champion Sebastian Vettel caused a stir in 2022 when he said climate change made him question his job.

The sport set a target five years ago to achieve a net zero-carbon footprint by 2030, using 100% sustainable fuels by 2026, and its first Impact Report, released in April, said the footprint was reduced by 13% in 2022 compared to 2018.

Ellen Jones, F1's head of environment, social and governance (ESG), has said F1 has a "unique platform" to develop technological solutions to climate change and inspire international action.

So how does F1 plan to reach net zero, and do the plans stack up?

What are F1's biggest emissions?

F1 cars on the track are responsible for just 0.7% of the sport's emissions, which overall stand at around a quarter of a million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent - roughly the same as the annual emissions of 55,000 normal cars, according to a calculator from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The jet-setting nature of the F1 calendar, with more than 20 races taking place across five continents, means that travel and logistics make up two-thirds of the sport's footprint as teams, kit and fans travel vast distances.

Jones said they are tackling these emissions by constantly reviewing the amount of kit that has to travel, the modes of travel - such as lower-emitting trucks - and the calendar.

In 2024, for example, among other changes the Abu Dhabi race is back-to-back with Qatar, unlike the 2023 season when teams had to travel all the way from Las Vegas.

But Benjamin Stephan, a transport expert at Greenpeace Germany, wants to see fewer races and a much more regionalised calendar to limit air travel.

He pointed out that in 2024 there are a record 24 grands prix, compared to 22 in 2023 and 16 when he first started watching as a child.

What is sustainable fuel?

A key part of F1's sustainability drive is the development by fuel manufacturers of new e-fuels, which synthesise captured CO2 emissions from sources like household waste into fuel.

While the cars still emit CO2, the idea is that these emissions will be equal to the amount taken out of the atmosphere to produce the fuel - making it carbon-neutral overall.

The hope is that the technology could decarbonise transport more broadly as internal combustion engine (ICE) cars still dominate the roads and e-fuels can be used in these and transported via existing fossil fuel logistics networks.

.

.

"Formula One's strategy is based on developing and showcasing road-relevant technical solutions," said Jones.

However, critics say manufacturing these e-fuels for ICE vehicles is expensive and energy-intensive, potentially requiring five times more renewable electricity than running a battery-electric vehicle, according to a 2021 paper in the Nature Climate Change journal.

"While that might be a super niche solution for Formula One, it's not a sustainable solution for the road transport sector," said Stephan from Greenpeace, adding that the sport should switch to all-electric instead.

Meanwhile, F1 is betting on new, sustainable fuel technologies to lower its logistical emissions as well.

Alice Ashpitel, Mercedes-AMG Petronas head of sustainability, said her team reduced freight and generator emissions by two-thirds during the 2023 European season by using a biofuel produced from residual waste products like cooking oil and animal fats.

With aviation accounting for a quarter of the team's carbon footprint, it is also investing in sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), which is not yet produced at scale.

Can F1 reach net zero by 2030?

The major challenge facing F1 is that, assuming all of these changes and technologies are successfully implemented, emissions cuts will only take the sport down part of the road to net zero emissions.

"Our focus is achieving a minimum of 50% reduction in emissions, with any unavoidable emissions then addressed with offsetting," said F1's Jones.

Offsetting emissions by, for example, investing in reforestation to absorb CO2 is a controversial practice. Emissions reductions from projects have often been difficult to verify, and critics argue offsets are often used by corporations as an excuse to keep polluting.

Jones said offsetting is the second phase of F1's strategy. She said they are monitoring the landscape as the offset market develops quickly, and that standards are regularly being revised to ensure high integrity.

Madeleine Orr, an assistant professor at the University of Toronto and a researcher in climate and sport, said a fully sustainable F1 would require more significant compromises, such as major rescheduling, changes to the competition and limits on merchandise.

Orr, who has done sustainability work with an F1 team, said progress so far varies significantly between teams, but she said they should work together with organisers to make greater gains on sustainability while remaining competitive.

"It's possible to compete on the race circuit while collaborating on the race to zero," she said.

"If F1 can get that right, it would be a model for the whole sports world to follow."

This article was updated on May 3 to add details about the 2024 Formula One season.

(Reporting by Jack Graham; Editing by Clar Ni Chonghaile and Laurie Goering)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Net-zero

- Climate policy

- Carbon offsetting