'No doctors, no nurses, no equipment': Inside a Syrian hospital

A medical worker walks inside the Aleppo University Hospital that is damaged by strikes, after rebels have staged a whirlwind advance over the past week, seizing Aleppo and much of the surrounding countryside, in Syria December 4, 2024. REUTERS/Mahmoud Hasano

What’s the context?

Syria's public healthcare system teeters on the brink of collapse after years of war and sanctions.

- Syria's healthcare system is crippled by war, sanctions

- Patients depend on poor public services

- Only 57% of hospitals are fully functional

DAMASCUS - Like a mother duck leading her ducklings, gastroenterologist Bashar Hamad steers dozens of white-coated trainee doctors through the dim hallways of Damascus's Al Mojtahed hospital, a crumbling symbol of Syria's devastated healthcare sector.

Blood treatment machines, many of them missing vital parts, clutter the dingy wards, where rooms lack doors and floors are covered with dirt and leaking water.

The derelict hospital is a legacy of former leader Bashar al-Assad's brutal rule. He presided over a vicious crackdown against dissent, and a 13-year civil war led to the imposition of crippling sanctions that decimated the economy.

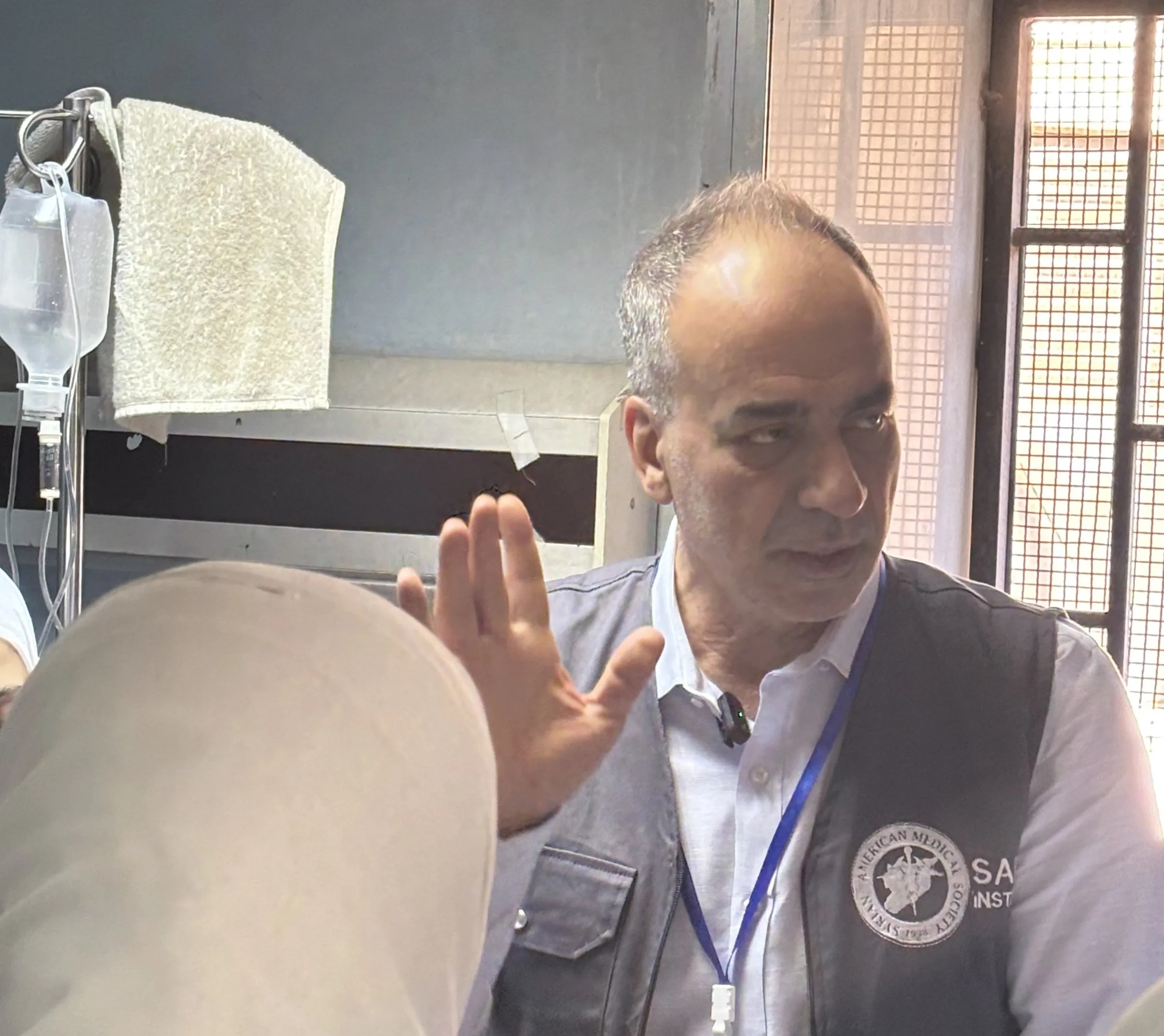

"They left the country with no doctors, no nurses, no equipment and a bad healthcare system," said Syrian-born Hamad, who lives in the United States and is volunteering in Damascus.

"Considering what they have in their hands, they (local doctors) are doing a wonderful job ... There are not enough resources. That's not safe for the patient."

Assad was ousted by Islamist-led rebels in December, but his 24-year presidency and years of violence and sanctions have brought the healthcare sector to near collapse.

Only 57% of hospitals and 37% of primary healthcare centres remain fully functional, a United Nations assessment said in May.

Between 50% and 70% of health workers left the country during the war, the assessment said.

In Al Mojtahed, Hamad said anaesthesia is rarely available and if so, it is often administered by general doctors instead of specialists.

Single-use surgical balloons are used multiple times after being manually cleaned. Needles are sterilised in soap and water in grimy basins.

"Syria's public health sector remains at a critical juncture," said Christina Bethke, acting representative for Syria for the World Health Organization (WHO), in emailed comments to Context.

"Syria's poorest communities have been hardest hit," she added. "Negative coping mechanisms may result when families face catastrophic health expenditures and have to choose between life-saving health care and other necessities like food, water and education."

But for residents like Mohammad Abed, a wheat farmer from the northeastern city of Raqqa, more than 400 km (about 250 miles) away, state hospitals are nonetheless the best option.

Abed, like most Syrians, cannot afford to pay privately for medical treatment.

Between 2004 and 2022, private hospitals in Syria increased their bed capacity by 70%, while public hospitals saw a 40% increase during the same period, according to the Syria Report newsletter, citing Syria's Central Bureau of Statistics.

Abed raised about $70 from family and friends to travel to the Mouwasat University Hospital, another state hospital in Damascus.

"We have nowhere else to go," he said after undergoing an endoscopy procedure.

'We have to do something to help'

Hamad has been working with the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS), a relief organisation, since the civil war broke out in 2011.

Sometimes he helped displaced Syrians in Lebanon and in Syrian areas outside Assad's control. After the president was ousted, he started coming to Damascus.

"I had a feeling that we have to do something to help the ones who have no money to get treatment," he said in an interview between ward rounds.

During Assad's rule, Western sanctions made it difficult to obtain drugs, equipment and foreign expertise.

The United States and the European Union pledged to lift sanctions in May, and this week U.S. President Donald Trump signed an executive order terminating a sanctions programme against Syria.

Nevertheless, the U.N. says more than 15 million Syrians - out of a population of 23 million - are in "dire need" of primary or secondary health assistance.

Some 7.4 million people remain displaced inside the country, living in overcrowded camps or informal settlements where outbreaks of cholera, measles and other diseases are common.

In northwest Syria, once a rebel stronghold, 172 health facilities could shut down due to funding cuts, while in the northeast, 23 health facilities have closed and another 68 are at risk of shutting, UN agencies said in May.

Alaa Armouse, sitting in a waiting room in Al Mojtahed, said he came with his sick brother from the northwestern province of Aleppo to get treatment for kidney disease.

"Our hospitals (in Aleppo) are not equipped. We don't even have blood bags," he said. "The treatment is better here."

Elham Kiwan said she came to Al Mojtahed from the southern province of Sweida with her husband, who needed open heart surgery.

"We do not have that in Sweida. The doctors here are great," she said.

Her husband lay next to her in the hallway, as the hospital has no post-operation recovery rooms.

The WHO says it is providing health care for more than half a million people across Syria with $3 million worth of funding from the UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF).

With partners, it delivers emergency health kits and treatment courses to health facilities and mobile medical teams.

But with needs so monumental, patients like Aysha Mahmoud are suffering.

She has been coming to Al Mojtahed for years for treatment for stomach pain and bleeding. But her body is not responding well, and sometimes the hospital runs out of her medicine.

"There is no money coming to the hospital for them to get my medicine," the young woman said between sobs as she lay in a gloomy hospital room.

"When they are out, my symptoms come back."

(Reporting by Nazih Osseiran; Editing by Clar Ni Chonghaile and Ellen Wulfhorst.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Government aid

- Wealth inequality

- War and conflict

- Poverty

- Cost of living