Refugees worldwide face hunger as donors slash aid

A villager uses a wheelbarrow to collect a monthly food ration provided by the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) in Masvingo, Zimbabwe, January 25, 2016. REUTERS/Philimon Bulawayo

What’s the context?

Food rations cut and cash transfers stopped: the cost of aid cuts in the world's refugee and displacement camps.

LAGOS - As funds dwindled, the World Food Programme last month issued an urgent SOS to donors: it could no longer deliver food to 1.3 million people displaced by conflict and extreme weather in Nigeria's northeast and its operations were about to collapse.

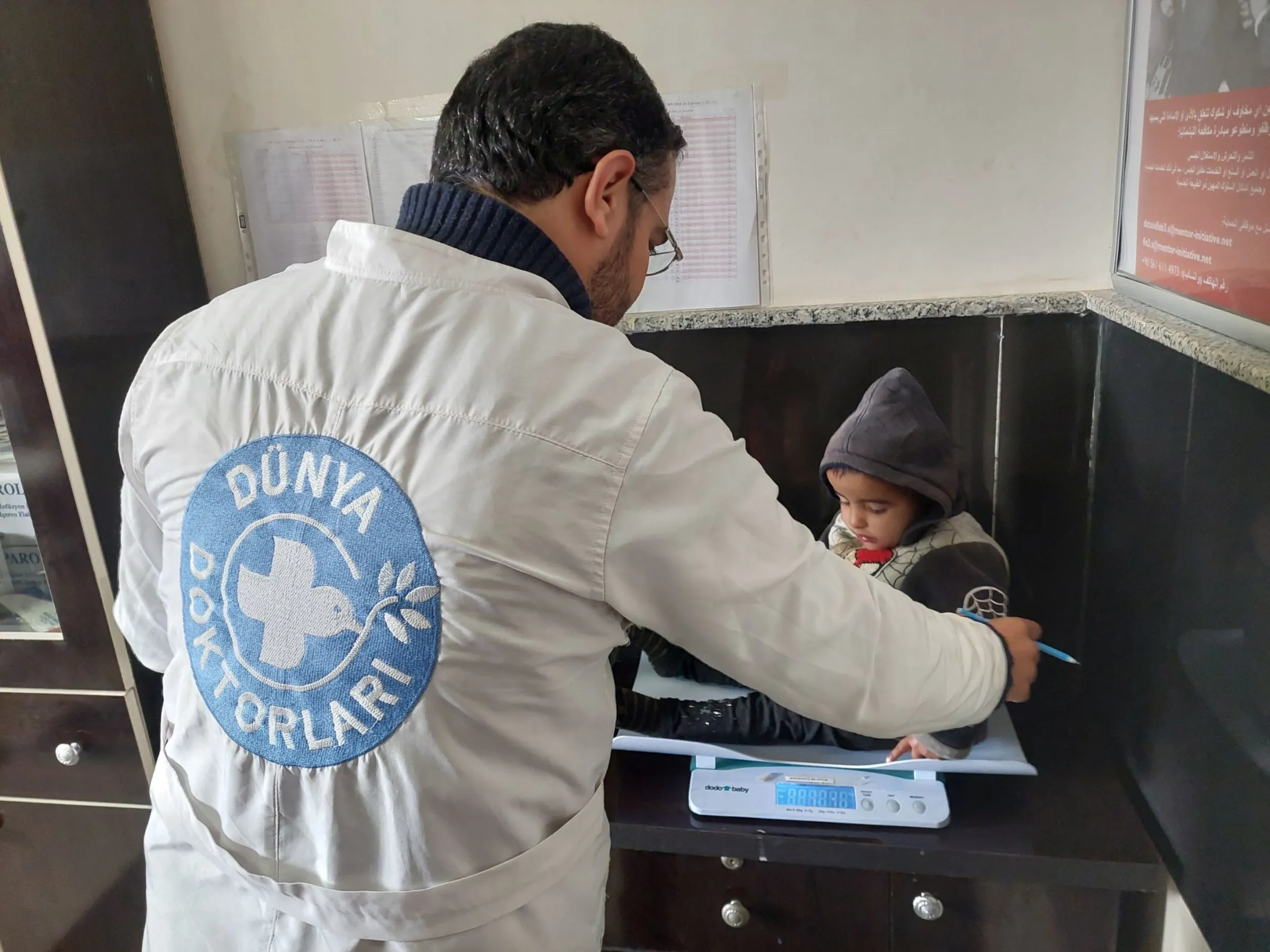

The U.N. agency, the largest provider of global food aid, said it had already distributed its last grain reserves and that without new funding, it would have to shut down 150 nutrition centres treating 300,000 malnourished children.

Without "immediate and sustained funding", its operations, supported by Canada, Britain and other international donors, could cease entirely in the region, it said.

Global humanitarian operations were thrown into chaos this year after President Donald Trump gutted U.S. aid programmes. In May, Reuters reported that food rations that could supply 3.5 million people for a month were mouldering in warehouses around the world.

Already, international aid had fallen in 2024 for the first time in six years, and is set to plunge further this year.

Here is how the cuts are hitting food supplies in refugee camps around the world, from Kenya to Bangladesh.

Why are food aid budgets collapsing now?

Before the Trump administration dismantled the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) this year, it played a major role in funding global food aid, giving $5 billion annually to food assistance programmes.

The United States was the WFP's largest donor in 2024, providing around half the $9.75 billion the U.N. agency received.

Western donors, including Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Belgium, have also scaled back international aid due to inflation, shifting political priorities, climate disasters and increased commitments on defence spending.

An analysis by global nutrition leaders published in the scientific journal Nature in March said that aid cuts by the United States and other major donors amounted to a 44% cut in international support for global nutrition programmes, which totalled $1.6 billion in 2022.

It said the cuts could deprive 2.3 million infants of life-saving treatment in low and middle-income countries and lead to 369,000 extra child deaths a year that would otherwise have been prevented.

How are refugee and displacement camps being affected?

Aid organisations say hunger levels are soaring in these camps as families skip meals and warn that the shortage of food aid increases the risk of unrest in camps.

In July, protests broke out in Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya - home to more than 300,000 refugees from Somalia, South Sudan, and Ethiopia - after aid workers cut food rations due to funding cuts.

In Uganda, WFP said it had to cut food aid for about one million refugees and slashed rations by up to 80% as funds shrunk.

In Sudan, local organisations funded by USAID have closed several emergency food kitchens due to funding cuts.

U.N. food programmes in Ethiopia have run out of nutrient-rich foods used to treat around one million severely malnourished children annually and WFP warned earlier this year that 3.6 million of the "most vulnerable" people would lose food and nutrition assistance unless funding arrives urgently.

In Bangladesh, WFP reduced food vouchers for more than one million Rohingya refugees in March and said it would have to slash the $12 each refugee receives monthly to $6 without urgent funding.

In Haiti, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs said aid organisations have had to stop cash transfers that families used to buy food due to a funding freeze.

What is the way forward?

Humanitarian groups stress the first priority is to urgently replenish food aid budgets to prevent deeper cuts in refugee camps.

The U.S. State Department, which now oversees USAID, said in August it would provide $93 million in food aid packages to 12 African nations and Haiti over the next year.

The aid, to be delivered by the U.N. children's agency UNICEF, includes the distribution of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) and funding to produce it.

This is far from the billions of dollars aid agencies say are needed: WFP says it needs $5.7 billion to reach 98 million vulnerable people in 2025.

Aid experts say the international community should work with governments in low and middle-income countries to pressure development banks to increase funding for global nutrition funding.

(Reporting by Bukola Adebayo; Editing by Jon Hemming.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Government aid

- War and conflict

- Poverty