Reporter’s notebook: Meeting LGBTQ+ refugees in Kenya

Ronnie (left), a Ugandan refugee living in Kenya, shares his story with Context reporter Enrique Anarte (middle) and videographer Nyasha Kadandara (right), in Nairobi, on July 12, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Evelyn Kahungu

What’s the context?

As anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment sweeps East Africa, we met asylum seekers in Nairobi who no longer feel safe in the country they fled to

There’s so much that doesn’t make the final cut of a film.

A few months ago, my colleague Sadiya Ansari and I went to Nairobi to film a documentary about LGBTQ+ asylum seekers in Kenya, which for years was seen as a safe haven for queer refugees.

What we saw was something different.

We met four queer asylum seekers trying to live invisible lives, fearful a neighbour may become their next attacker or an official might find a way to extort the little money they have.

What didn't make the cut of our film were the many plans they nurtured of building a life far from ones lived in limbo in Keyna.

What didn't make the cut were the dreams they nurture of a life far from here - after all, their hopes are being held prisoner to the present that has entrapped them in Kenya.

Some of them decided to go in front of the camera despite the risk speaking out in a country where they face widespread discrimination and even violence, where same-sex relations are criminalised and where a bill being discussed could toughen those laws even further.

Ronnie, Kevin, Emmalia, Lawrence.

These young Ugandans shared with us what made them flee home, what their lives are like in Kenya and what they hope the future holds.

They showed us - and the camera - their bedrooms, kitchens where they prepare recipes they brought from home and living rooms where they spend hours waiting for a piece of paper that might never come - the government document acknowledging their refugee status.

They had clearly tried to make themselves feel at home in Kenya. But none of them wanted to stay here. They all wanted to leave - again.

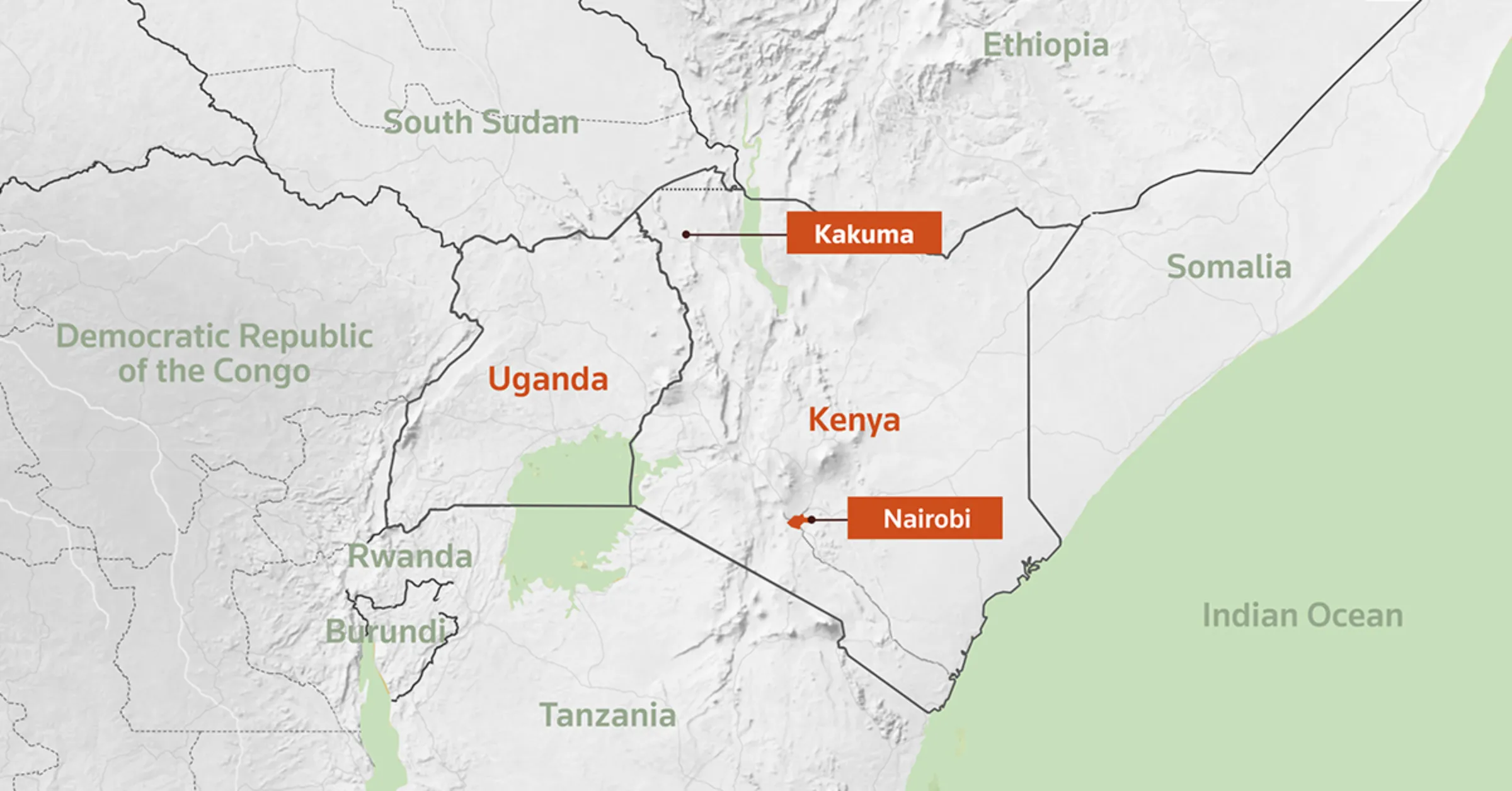

The shelters where they live are places you cannot find on Google Maps. Many of them live in hiding in Nairobi after having fled Kakuma refugee camp, where they have been targeted by fellow asylum seekers.

The government says that the average wait time to be officially recognised as a refugee is 12 months, but people like Ronnie have been waiting for six years.

He and others are trapped in a system that’s dealing with a backlog of cases since the COVID-19 pandemic.

But Kenya’s policies towards LGBTQ+ asylum seekers in particular are changing as the anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment sweeping East Africa and beyond has started to take root in the country.

Kenya’s refugee commissioner has said persecution based on sexual orientation or gender identity is not grounds for asylum.

Without documentation, refugees cannot work legally in Kenya, and they cannot officially apply for resettlement through the United Nations refugee agency UNHCR.

The UNHCR said in 2021 there were about 1,000 LGBTQ+ asylum seekers and refugees in Kenya. That number has probably risen since Uganda passed the Anti-Homosexuality Act in 2023.

The law includes the death penalty in some cases and criminalises not only same-sex relations, but also the “promotion” of homosexuality and has been blamed for hundreds of cases of abuses and violence, according to the UN.

Emmalia was one of them.

She had been an out trans activist for years, but in September 2023, four months after the legislation was signed into law, a mob tried to set her on fire. So she fled to Kenya.

We met at a Pride event for refugees in Nairobi. Dressed in a purple dress stamped with white flowers and wearing a bracelet with the colours of the Kenyan flag, she was the charismatic host of the evening’s festivities.

While people ate and drank and we sorted out the release forms for permission to use the images of trans women we had filmed on a makeshift runway, Emmalia approached me to ask what we were filming.

I told her it was a documentary about LGBTQ+ refugees in Kenya. She said she wanted to share her story, and we agreed to meet the following week.

Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

The moulds, the expectations people have of LGBTQ+ activists in Africa, were too small for Emmalia.

She told us about how she had to leave her family, change schools, about how her mother tried to get her to be quieter when her desire to scream for the rights of her community couldn't be contained a minute longer.

But when spoken about the traditional wedding that brought together her family and that of her back-then partner, I thought my hearing loss was playing against me. I myself had enclosed her in a box she was breaking into pieces.

I listened as she told me about finding love here in her Kenyan exile, and her dreams of a future together with her current boyfriend - and the possibility that one of them reaches that long-awaited resettlement, even if that means having to part.

"Where there is love, everything is possible," she sentenced, hope shining in her eyes.

How do those details make to the final cut of a film; how do we make them fit a story that not only needs to fulfill our editorial standards, but also brave the algorithmic waves that bring stories to our shores?

Ronnie’s dream of owning a food truck and selling Ugandan fare in the streets of New York City also didn’t make the cut. Neither did the rendition of an Enrique Iglesias hit song that he and his friends sang when I first told them my name.

They were good singers, actually. They said they should start a record label together one day. For now, they are still waiting, trapped in a country that won’t let them build a life but also won’t let them leave.

This content is part of a series supported by Hivos's Free To Be Me programme.

(Reporting by Enrique Anarte-Lazo; Editing by Ayla Jean Yackley and Sadiya Ansari.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- LGBTQ+

- Poverty

- Migration