South Africa's 'wild west' WhatsApp groups fuel racism, surveillance

The WhatsApp app logo is seen on a smartphone in this picture illustration taken September 15, 2017. REUTERS/Dado Ruvic

What’s the context?

From Johannesburg to Durban, community WhatsApp groups have thrived during the pandemic, but they can feed paranoia, racial profiling and vigilante surveillance, researchers say

-

South African crime rates among the world's highest

-

Local WhatsApp groups used for neighbourhood surveillance

-

Groups need a moderator to avoid racism, say experts

DURBAN - When South African content manager Happiness Kisten chased her family's escaped puppy up the road in the early hours of the morning in her Durban suburb, she did not realise she was being watched.

But when Kisten, a Black South African adopted by Indian parents, arrived home puppy in tow, her mother showed her a message on the neighbourhood WhatsApp group that warned residents about a Black woman seen running after a dog.

"At first I laughed, but afterwards I was like, that's very problematic. It left me with an ugly feeling in my gut," said Kisten, 29, who had previously left the group when she became uncomfortable with the racial prejudice she witnessed there.

South African crime rates are among the world's highest, and criminologists say growing disillusionment with the police has contributed to a rise in community WhatsApp groups where residents engage in amateur surveillance.

While such groups can forge stronger community ties, researchers say that without proper moderation by an internal mediator, they can become hotbeds for fear-mongering and racial profiling in a country still scarred by apartheid segregation.

Although exact numbers of community security WhatsApp groups are nearly impossible to track, South African security analyst Ziyanda Stuurman said the unregulated "wild west of social media" surveillance is becoming more common.

COVID-19 lockdowns heightened people's desire to connect through social media, but the trend also saw more disinformation circulating and fed long-standing paranoia about crime, said Stuurman.

"Fake news can spread quickly and this can lead to real violence," said Stuurman, pointing to the July 2021 riots in the country that led to mass vigilantism when social media was ablaze with unverified content.

"We can start to see threats around every corner," she said.

Apartheid past

The widespread use of social media has led to an explosion in neighbourhood groups around the world, including for surveillance, with residents even reporting on each other for alleged breaches of coronavirus quarantine rules.

Anthropologist Leah Davina Junck, who studied her local neighbourhood WhatsApp group in Cape Town for over a year in 2016, found so-called couch patrolling from the window or on the way to the shops - with quick and fast assumptions pulled from fleeting sightings - was widespread.

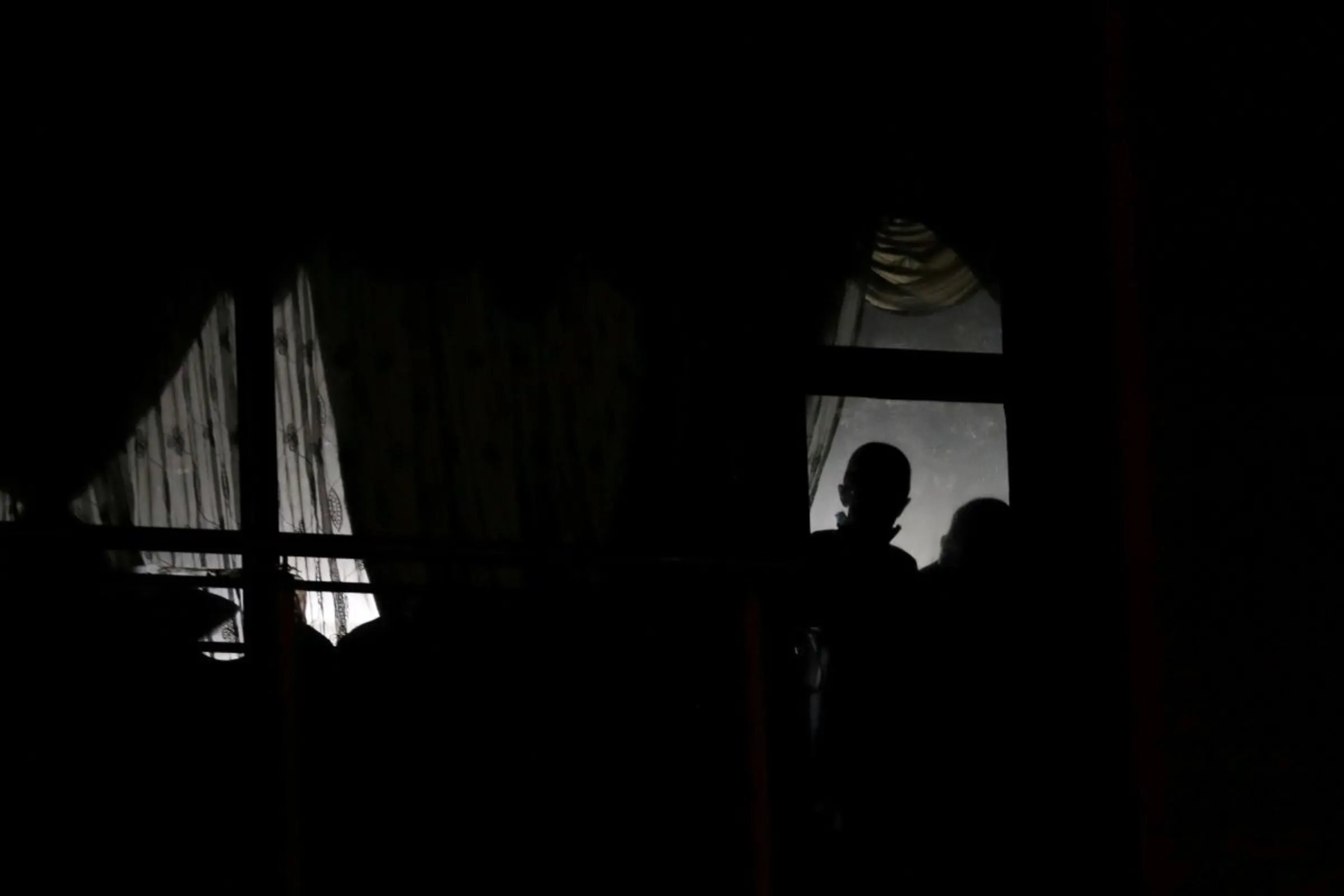

A resident looks outside the window amid a nationwide coronavirus disease (COVID-19) lockdown in Mayfair, South Africa May 1, 2020. REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko

A resident looks outside the window amid a nationwide coronavirus disease (COVID-19) lockdown in Mayfair, South Africa May 1, 2020. REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko

Code names to describe different races quickly became the norm, for example Charlie for Coloured - a term for mixed race in South Africa, Bravo for Black, and Whiskey for White, Junck found.

Kisten witnessed code language evolve into tangible violence.

When a Black former employee of Kisten's neighbour who was fired after drinking at work turned up to ask for his job back, it unleashed a flurry of WhatsApp messages that quickly escalated, said Kisten.

Two local residents attacked the man who was taken away by private security, with no repercussions for his assailants, she said.

"I can understand the point of the groups if they're used to alert people about real crime, but if someone is perhaps working in the area as a labourer or domestic worker, it doesn't make sense to be profiling this person," said Kisten.

Police said during the July unrest last year that under the Cybersecurity Act, anyone inciting violence online could face a fine or three years imprisonment.

Stuurman said homeless people were widely seen as suspicious characters in her Cape Town neighbourhood and residents messaged that they "felt bad" but were calling the police anyway "because they shouldn't be here".

"It really pulls us apart from each other in ways that are reminiscent of the apartheid past ... the paranoia feeds the belief that someone shouldn't be in my neighbourhood, and I feel entitled to whip up a frenzy about it," she said.

Community policing

In South Africa, fighting crime is a booming industry.

It is home to almost 2.5 million private security officers and nearly 10,500 registered security businesses, according to the country's Private Security Industry Regulatory Authority (PSIRA), making it among the world's largest.

Staff from private security companies and police officers are often members of neighbourhood WhatsApp groups.

A security guard leans against a wall in Sandton in Johannesburg, South Africa, 8 October 2019. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

A security guard leans against a wall in Sandton in Johannesburg, South Africa, 8 October 2019. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Teacher Khomotso Alvina Modjadji joined her local WhatsApp group of 250 members in 2018 when a neighbour in the Thembisa township near Johannesburg told her about it.

In the mainly Black neighbourhood, the group is not about racial profiling, but rather a way to feel more secure, and that "the community is part of the police service", she said.

"The group makes me feel safer. For instance: the other day someone posted about a certain car going around robbing people, so instead of bringing my laptop home I left it at school," said the 31-year old.

Having police officers in the chat helps, she added.

"If there is a problem, the community goes as a group, and they can do a citizen arrest and the police officers in the WhatsApp group come quickly," she said.

The police did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Monitoring conversations

There are ways for WhatsApp neighbourhood groups to minimise the risk of targeting innocent people, including by having a moderator "who mediates and monitors the conversations, and sets out some rules of engagement", said Kisten.

There are other platforms or avenues for community policing, said Stuurman, such as local Community Policing Forums (CPF) -groups that are created specifically to patrol neighbourhoods alongside police officers.

"There's a fine balance between connecting with neighbours in these chats and turning them into digital surveillance platforms," she said.

Some months back, a power cut meant that Stuurman could not open the automated gate outside her building. She sent a message on her building's WhatsApp chat, and a neighbour came to open the gate for her manually in less than a minute, she said.

"We need to see whether these groups can become less about surveillance and more about community," she said.

(Editing by Helen Popper.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Polarisation

- COVID-19

- Race and inequality

- Tech and inequality

- Corporate responsibility