Resistance blooms in Mexico's data centre valley

What’s the context?

Community resistance grows in Mexico as locals feel the environmental impact of the data centre boom and empty promises.

Homemaker Rita Zeferino lives in Mexico's semi-desert state of Querétaro, where a data centre boom promoted by the government has left residents facing strict water rationing and power cuts.

The state is prone to drought, and residents say the needs of data centres are worsening water shortages and straining the electricity grid.

"Sometimes we get water, sometimes we don't," said Zeferino, 48, who lives in the town of Viborillas, surrounded by multiple data centres.

"And sometimes we get water, but it's dirty."

Women from the Antorchista movement gather for a discussion on water and energy issues in the town of Viborillas, Querétaro, Mexico. July 25, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Miguel Tovar

Women from the Antorchista movement gather for a discussion on water and energy issues in the town of Viborillas, Querétaro, Mexico. July 25, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Miguel Tovar

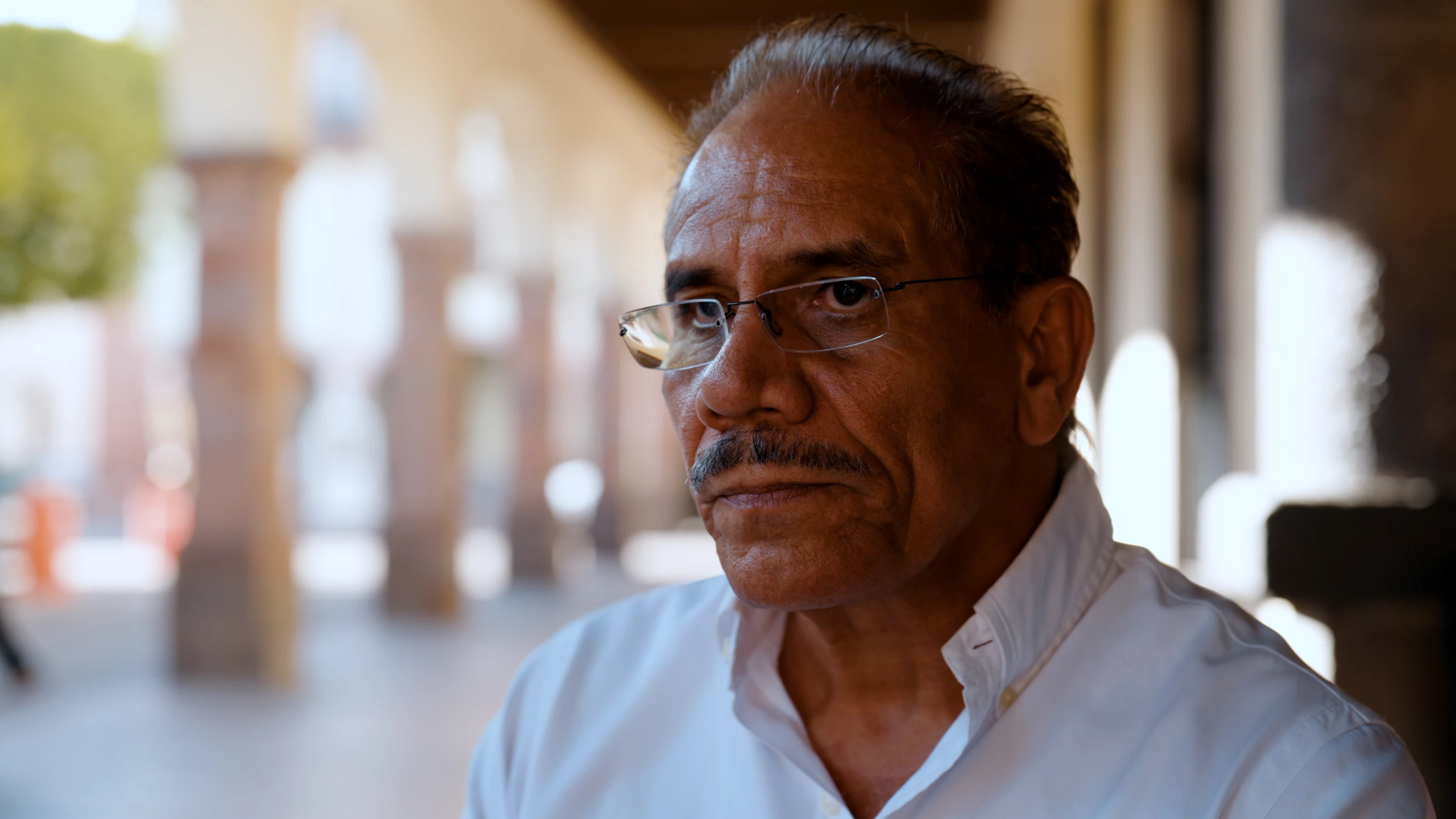

Taxi driver Felix Farfán said he has seen a sharp hike in his electricity bills and more frequent power cuts since a data centre near his home in Ajuchitlán began operating in 2024.

Over the past year, his monthly power bill jumped from 800 pesos ($400) to 1,200 pesos ($600) despite constant power cuts, he said.

"I think of my grandchildren," he said. "I'm worried about the future, what will the new generation inherit?"

Félix Farfán, local taxi driver concerned about data centres' impact on rising power cuts and water shortages in Querétaro, Mexico. July 24, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Miguel Tovar

Félix Farfán, local taxi driver concerned about data centres' impact on rising power cuts and water shortages in Querétaro, Mexico. July 24, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Miguel Tovar

But residents are finding ways to demand greater transparency and accountability from big tech companies and government officials about the impact of data centres.

Zeferino belongs to the National Antorchista Movement, a group that lobbies the Querétaro government to end water shortages and demand information about industry water consumption.

They are faced with strong support for data centres, however, that reaches to the top echelons of government.

President Claudia Sheinbaum has promoted data centre construction nationwide, with Querétaro getting investments of $12 billion since 2022 from big tech companies like Microsoft, Google and Amazon.

A dozen data centres operate in Querétaro, and plans call for up to 10 more.

One of the most robust investments came from U.S. tech firm CloudHQ, which in September announced a $4.8 billion project to build six data centres by 2027 and provide 900 permanent jobs.

Read more: Thirsty data centres spring up in water-poor Mexican town

Resource intensive

Data centres are warehouse-like buildings, some as big as sports stadiums, where servers store the global internet's vast social media posts, documents, photos, videos and databases.

Hyper-scale data centres, like those built in Querétaro, are the physical locales housing generative AI tools such as ChatGPT, Gemini and Copilot.

Data centre under construction in Querétaro, Mexico. July 25, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/ Miguel Tovar

Data centre under construction in Querétaro, Mexico. July 25, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/ Miguel Tovar

Data centre servers run uninterrupted day and night and require not only a constant power supply but cooling systems to stop their computer systems and chips from overheating.

The cooling systems typically require massive amounts of water.

Adriana Rivera, head of the Mexican Association for Data Centres, an industry group, said most data centres in the country are not big consumers of water as they use water efficient cooling systems.

"When it comes to water, we are, practically speaking, shielded by technology," Rivera told Context.

Yet residents of Viborillas face long and unpredictable water shortages.

Some residents say they get water just three days a week. Others say they have gone without water for as long as a month.

"It feels like a party when we have water. Our homes come alive because we wash clothes or dishes, or we collect it for consumption or for cooking," said Brenda Álvarez, a 36-year-old mother.

Like Zeferino, she has joined the Antorchista group to demand answers from the government about not only data centres but other water-intensive industries like chicken farms, housing developments, greenhouses and car manufacturers.

"Companies use significant volumes of water, millions of litres to produce their products," said Jerónimo Gurrola, who heads the Antorchista group in Querétaro.

Jerónimo Gurrola, who leads the Querétaro chapter of national Antorchista Movement, sits at an interview in Querétaro, Mexico. July 26, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Miguel Tovar

Jerónimo Gurrola, who leads the Querétaro chapter of national Antorchista Movement, sits at an interview in Querétaro, Mexico. July 26, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Miguel Tovar

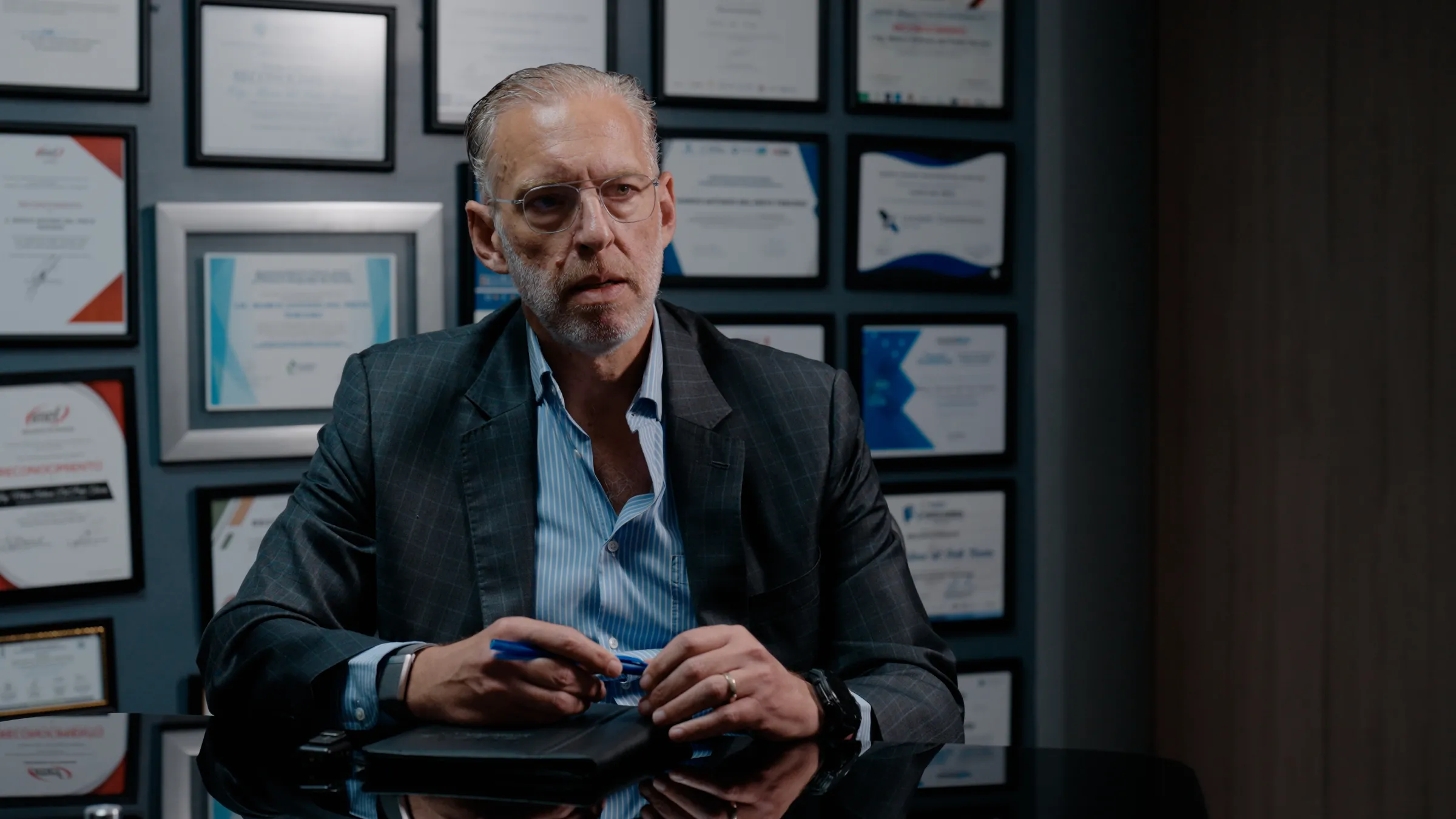

Marco del Prete, Secretary of Sustainable Development in Querétaro who has led the effort to attract data centres, told Context that blaming water shortages on data centres is "simplifying" the problem as water issues predate them.

Mexico's president has welcomed the foreign investment as a sign of trust in the nation's economic stability, saying data centres are necessary for the country "to advance in artificial intelligence" in the "new economy."

Sheinbaum said the government is looking for solutions to address water issues, but activists are sceptical.

"To this day, people lack drinking water and are forced to walk hours between the hills, between the mountains, to find small springs," Gurrola said.

Read more: The AI race could make net zero impossible. Here's why

Thirsty AI

Details about how much water is used by data centres are murky within the global industry, where information can be hidden in non-disclosure agreements with governments, omitted from sustainability reports or simply be unreliable.

The Querétaro government exempts data centres built within industrial parks from issuing environmental impact reports which typically cite the amount of water needed for their operations.

In Querétaro, small volunteer groups like Voceras de la Madre Tierra (Spokeswomen for Mother Earth) have submitted public information requests and organised public forums to pressure the local government to disclose how much water is allocated to data centres.

Their requests have gone unanswered.

That activism, however, has drawn death threats and online harassment for Teresa Roldán, a high-profile member of the group.

Teresa Roldán, activist of local environmental group Voceras de la Madre Tierra, in an interview in Querétaro, Mexico. July 22, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fintan McDonnell

Teresa Roldán, activist of local environmental group Voceras de la Madre Tierra, in an interview in Querétaro, Mexico. July 22, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Fintan McDonnell

"These data centres are in the middle of areas that were used for aquifer recharge, agriculture, or livestock farming, which is a source of income for many families," said Roldán.

"These centres have taken that income away from them," Roldán told Context.

Read more: Data centres lured to Mexico can avoid environmental reporting

Lights off

Three years ago, when Querétaro officials announced the arrival of Microsoft's data centre in La Esperanza, Farfán said he had no clue what a data centre was but learned quickly.

"We started to realize there are constant electrical failures in which we lose power and electricity transformers blow," said the taxi driver.

"We started to research and there's a latent suspicion … that it's related to the operation of these data centres."

Del Prete rejected the suggestion that power cuts are linked to data centres, saying they are instead related to the inadequate energy infrastructure.

Two drone shots of different data centres in Querétaro (left), and Marco del Prete, Querétaro's Secretary of Sustainable Development (right), sits at his office for an interview with Context in Querétaro. July 28, 2025. Miguel Tovar/Thomson Reuters Foundation

Mexico's power grid is already deficient, stretched by the demands of industry, rising electricity needs due to heat waves and a growing population.

Currently there is a nationwide installed capacity of 200 megawatts (MW) for data centres, with plans to install 1.5 gigawatts (GW) by 2030, according to the Mexican Data Centre Association.

This would eat up 5% of all new energy capacity that Mexico plans to build by 2030, according to the latest national energy plan.

CloudHQ, whose data centre complex will have some of the highest energy demand in the country, said it is investing $250 million to build the infrastructure that will power the initial 200 MW it requires in Querétaro.

"A data centre of that size is a city - not a town, but a legitimate city - worth of electricity generation right next door," said Masheika Allgood, founder of AllAI Consulting, which informs on the environmental impact of data centres.

Read more: AI data boom in Mexico fuels rise in dirty energy

Lost promises

The data centre boom in Querétaro began in 2020, with Microsoft announcing a $1.3 billion investment in its cloud and AI infrastructure that it said would help create some 300,000 jobs in various industries.

But, according to Microsoft's own figures, in 2025 it had 64 people working in one data centre in Mexico and expected to add up to 2,200 jobs during peak construction of two new data centres.

In response to the lofty employment promises, local universities had launched new curriculums for students to prepare.

Microsoft’s mobile school for the community of La Esperanza, Queretaro, Mexico. July 25, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/ Fintan McDonnell

Microsoft’s mobile school for the community of La Esperanza, Queretaro, Mexico. July 25, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/ Fintan McDonnell

But most jobs created have been temporary, such as construction workers hired while the data centres are built or permanent jobs that are low level such as security and cleaning, residents say.

"Unless you've got large tech companies who are building hubs in Mexico that will use these data centres, those jobs aren't coming," said Allgood.

Roads in the communities remain mostly unpaved, with poor public lighting and drainage systems, despite promises that data centres would bring improvements.

"If you balance the damage of these companies with their apparent benefits, there really aren't many," said Roldán.

Audience at a community forum at the Autonomous University of Querétaro about a water bill that proposes recycling sewage water for domestic consumption. Querétaro city, Querétaro, Mexico. July 22, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/ Fintan McDonnell

Audience at a community forum at the Autonomous University of Querétaro about a water bill that proposes recycling sewage water for domestic consumption. Querétaro city, Querétaro, Mexico. July 22, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/ Fintan McDonnell

Pledging community development, in 2022, UN-Habitat announced Microsoft would apply urban planning and sustainability expertise to "improve the quality of life of the communities near the data centres that the company plans to build in Mexico," according to a press release.

The promised programme, to be run by Microsoft, involved a $3.9 million investment in 21 community projects in the municipalities of Colón and El Marqués in Querétaro.

Visits by Context to the sites for the 21 projects in late 2025 found all but two were not completed.

In La Esperanza, a Microsoft data centre sits next to an abandoned outdoor gym and an unkempt soccer field that had been slated for improvement under the programme.

Broken lamps litter the field, rusting gym equipment is too hot to touch and the access road is riddled with treacherously deep potholes.

"Since I've been coming here, I haven't known of anybody that has come to improve it," said coach Víctor Manuel Chávez.

"This little field has been forgotten."

Victor Manuel Chávez, local football coach, practices at the community football pitch in La Esperanza, Queretaro, Mexico. July 24, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/ Fintan McDonnell

Victor Manuel Chávez, local football coach, practices at the community football pitch in La Esperanza, Queretaro, Mexico. July 24, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/ Fintan McDonnell

Mariana Lorena García, a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico investigating data centre impact, called the failure to complete projects "a form of extractivism."

"They come ask communities what they need, they write it down in a report, and then they don’t do anything," she said.

Neither Microsoft nor UN-Habitat responded to Context's questions about the projects.

Microsoft did build a mobile school next to the main square of La Esperanza with a company logo advertising computer and finance lessons.

But few people attend the school, said Marco Antonio Álvarez, who was among the first students to take a computer class there.

"I wish there were more people who would take advantage of this little school to have a better chance at life," Álvarez said.

Microsoft told Context the mobile school has trained 1,200 people on topics such as digital literacy, mobile phone use and AI.

Read more: As AI fuels growth of data centres, critics fight back

Blooming networks

Brenda Álvarez (right), resident of the Viborillas community, sits at a meeting with other local women who are part of the Antorchista Movement in Querétaro, Mexico. July 25, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Miguel Tovar

Brenda Álvarez (right), resident of the Viborillas community, sits at a meeting with other local women who are part of the Antorchista Movement in Querétaro, Mexico. July 25, 2025. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Miguel Tovar

In a visit to eight communities in Querétaro's so-called data centre valley, Context found residents gathering informally to learn more about data centres and their need for resources.

Likewise, academics are forming networks with environmental and rights groups to demand information from the government about the potentially harmful impact of data centres.

"There's tangible evidence that hasn't yet been quantified. But that's the goal of opacity, to prevent us from knowing," said Paola Ricaurte, professor at the Tecnológico de Monterrey University, who is researching data centre expansion.

"It has been, however, tangible for the people," she said.

Reporting: Diana Baptista and Fintan McDonnell

Editing: Anastasia Moloney and Ellen Wulfhorst

Photography: Miguel Tovar and Fintan McDonnell

Production: Amber Milne

Tags

- Tech and climate

- Tech and inequality

- Tech regulation