Hurricanes Helene, Milton force rethink of US disaster readiness

A Texas A&M Task Force 1 member with a human remains search dog scans an area following the passing of Hurricane Helene, in Burnsville, North Carolina, U.S., October 2, 2024. REUTERS/Marco Bello

What’s the context?

While the U.S. government spends billions on disaster relief, experts say more should be done to prepare for the next big storm

US Elections 2024: Read our full coverage.

- Flood maps often out of date, low accuracy

- Preference for disaster relief over prevention

- Disasters could lead to forward-looking policymaking

RICHMOND - The devastation wrought by Hurricanes Helene and Milton across the southeastern United States has prompted calls for a swift and comprehensive overhaul of disaster preparedness as climate change fuels bigger storms, wildfires and extreme weather.

From new flood map requirements to updating sometimes decades-old building codes, now is the time to at least think about getting ahead of the next storm, experts said.

"I never want to get the impression that even with (a) so-called Biblical storm, whatever that is, we can't do something about it. Because we know how to be resilient against flooding," said Chad Berginnis, executive director of the Association of State Floodplain Managers, a non-profit group.

The two hurricanes collectively killed more than 230 people and, in some parts of western North Carolina. Helene cut off entire communities.

A major factor that has compounded difficulties in the recovery is that the scale of the storm was so unprecedented that some areas were wholly unprepared to face the levels of water they saw. Flood maps drawn up by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) also underestimated the risk in many spots that were hit the hardest, the Washington Post reported.

Flood maps themselves are developed only to about the 50th percentile level of confidence, said Joel Scata, senior attorney at the non-profit Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC).

"So we're basically making development decisions based on the flip of a coin," he said.

"Congress needs to provide the funding for FEMA to increase that to the 95th percentile confidence level so we know exactly what we're getting into when developing these flood maps and making development decisions based on them," Scata said.

But FEMA's flood insurance rate maps are not predictions of where it will flood, and they do not just show where it has flooded in the past, said Luis Rodriguez, the agency's Engineering and Modeling Division Director.

"The (maps) are snapshots in time of a community's flood prone areas where minimum standards for floodplain management apply and the highest risk areas for flood insurance," Rodriguez said. "Flooding events do not follow lines on a map. Where it can rain, it can flood."

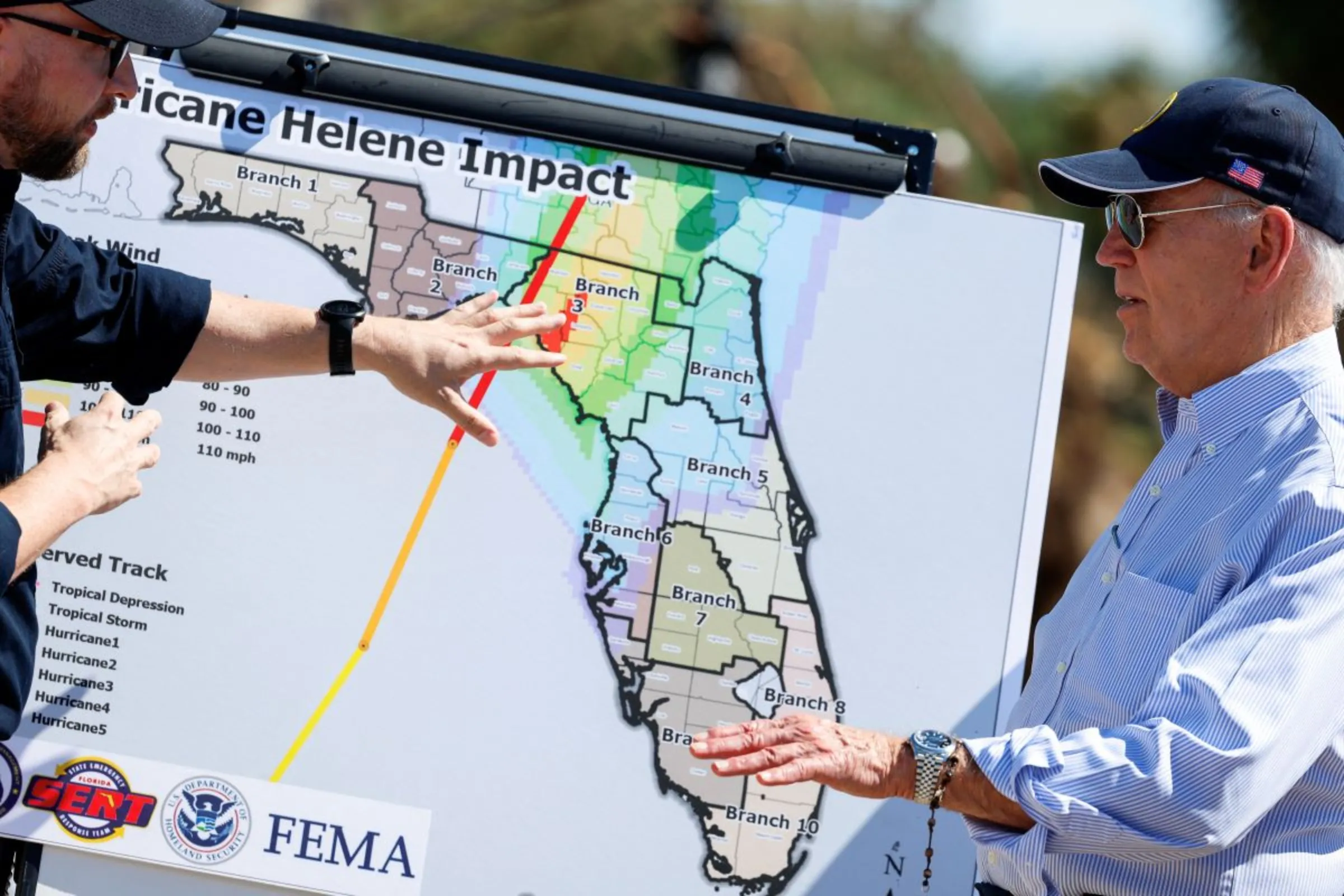

U.S. President Joe Biden receives information, as he visits storm-damaged areas in the wake of Hurricane Helene, in Keaton Beach, Florida, U.S., October 3, 2024. REUTERS/Tom Brenner

U.S. President Joe Biden receives information, as he visits storm-damaged areas in the wake of Hurricane Helene, in Keaton Beach, Florida, U.S., October 3, 2024. REUTERS/Tom Brenner

Berginnis said a significant portion of inland streams and rivers in the country were not properly mapped, which can provide a hazier picture of areas' actual flood risk.

"Congress has never appropriated enough money to getting the job done," he said. "There is a preference to spending money on disaster relief than on something preventative."

FEMA 'part' of the answer

FEMA has what it needs to continue response and recovery efforts for Helene and Milton, a spokesperson said, but funding issues mean the agency has had to temporarily pause non-emergency projects for at least two years in a row as the government faces the prospect of more "billion-dollar disasters".

However, the moves to "immediate needs" funding, while necessary at times, can have longer-term implications for projects intended to build resilience ahead of the next storm, said former FEMA administrator Craig Fugate.

"It really just makes everything more expensive – just look at routine inflationary pressure," said Fugate, who served in the Obama administration from 2009 to 2017. "You're having to postpone construction for three or four months, the price generally just keeps going up."

Fugate said FEMA was only part of the response to disasters, as grant and aid programmes are administered by other agencies like the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

"The tendency that everybody always focuses on FEMA I think is missing the point," he said.

"(In) a lot of these disasters, FEMA is not the answer – it's part of the answer, but it's not going to make families whole. You're going to need other programmes, especially HUD and the flexibility that Congress has given HUD to do the block grant programmes when they allocate money for disasters," Fugate said.

As an example of how states can effectively leverage those funds, Fugate pointed to former Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards' push to use HUD money to provide grants for residents to repair damaged homes after 2016 flooding rather than build new properties.

"That was probably a better solution than trying to build new housing or affordable housing," Fugate said. "That was really the first time I saw it done at that scale, but that may be something that will be needed to be done more frequently."

The Small Business Administration's (SBA) disaster loan programme for small businesses and individuals also just ran dry, but Congress is unlikely to reconvene until after the Nov. 5 elections to replenish it and potentially pass a new supplemental disaster funding bill.

'Setting themselves up for failure'

Berginnis pointed out that some past disasters had prompted significant state responses. Florida, for example, overhauled its building codes after Hurricane Andrew in 1992.

And in 2017, Hurricane Harvey prompted Texas "to begin to commit serous resources to dealing with flooding issues," he noted.

But North Carolina lawmakers went in the other direction last year, passing legislation that could make it harder to update building codes in the state until the 2030s.

"It really put them at a disadvantage, not only in terms of making sure that the homes that are going to be built in the future are going to be safer, but also for obtaining federal assistance," said the NRDC's Scata.

Under FEMA's Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) programme, for example, states compete for federal funding intended to help steel localities against future disaster risks.

"A lot of that is dependent on what they have already done, such as adoption of stronger building codes," Scata said. "And when states roll back building codes, like North Carolina did, they're just setting themselves up for failure."

Berginnis said that perhaps some forward-looking policymaking at the federal, state and local levels could come out of the recent disasters.

"OK, so let's say a community doesn't have good flood maps or flood maps at all. Well, they just had a flood, they know where the high-water mark is – make that your regulatory floodplain and make sure that you protect against that level," he said.

"Sometimes it's not complicated, and I think there are some very common-sense things we can do to be far more resilient than we are."

(Reporting by David Sherfinski; Editing by Jon Hemming.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Extreme weather

- Adaptation

- Climate policy

- Climate inequality