Data, trust and social change - the power of relationships

A sleeping bag is seen on the chair on the steps of the U.S. Capitol to highlight the upcoming expiration of the pandemic-related federal moratorium on residential evictions, in Washington, U.S., July 31, 2021. REUTERS/Elizabeth Frantz

Graphs and data can be a powerful tool to illustrate the injustices that result in people being evicted from their homes

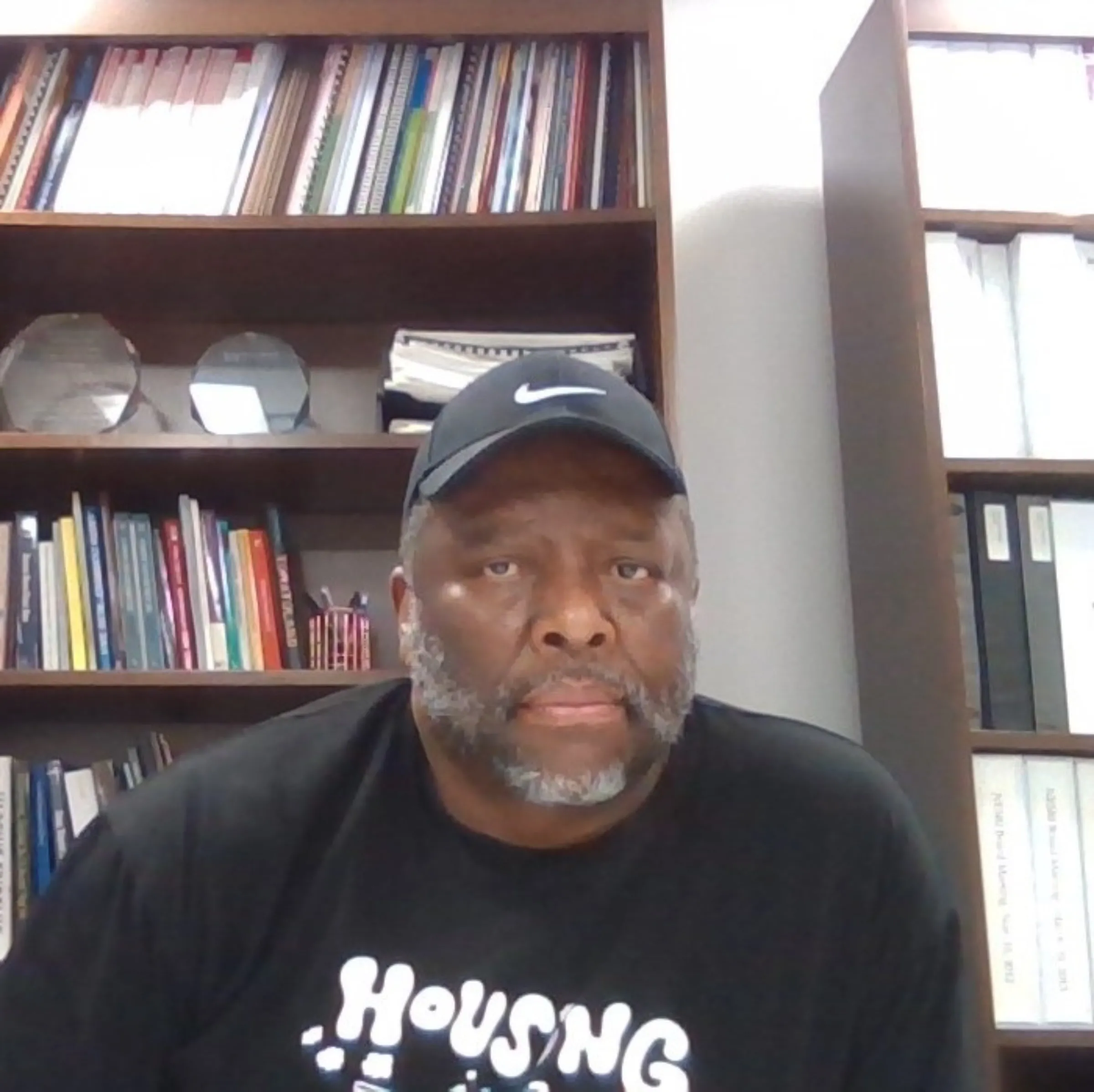

Robert Robinson is an advocate for the Data Values Project and the Data Values Manifesto, supported by the UN Foundation’s Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data.

Back in the mid-2000s, I was living in a housing shelter in New York City. The conditions were poor, and my fellow residents and I no longer wanted to put up with them. So, we began a letter-writing campaign to the executive director and board of the shelter, and luckily we caught their attention. I ended up working closely with these higher-ups, and began attending meetings of local organizations who were working to address the homelessness crisis in the US.

I realized that the more people I met and the more relationships I made, the more action I saw. By speaking openly about my experiences and sharing my story with others, change would slowly but surely start to be made. And the more people who become part of a movement, the more data there is to support our arguments. In our current world, data is the key to unlocking solutions to our problems and beyond.

Data allows communities to come together and create clear, authentic narratives and stories, which activate key decision makers into taking action. But data by itself doesn’t get the job done. It’s how we use data that allows us to truly make change. For example, New York City is the city in the US with the highest number of unhoused people, despite the existence of an open data portal for housing. The reason the portal isn’t doing its job is because it’s an information dump; it has no rhyme or reason when it comes to using the data within it and does not produce an output that is helpful to those accessing these services.

The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project is a data project based in New York City which clearly and simply shows the reality of homelessness. Collecting this data and translating it in a way that is easily digestible was key in getting policymakers to take notice of the high eviction rates in specifically low-income and minority neighborhoods. This data was not specially collected by the Project; in fact it was the very same data that was sitting untouched in the City’s open data portal.

There are dozens of other projects and coalitions which are using data to make change. In 2017, a law was passed in New York City which guaranteed legal counsel for those facing eviction.

The key to this was using data to show which housing courts were most likely to result in evictions and where evictions were most common, in terms of landlords and neighborhoods – again, using already available, public data.

But data is not as cut and dry as it may seem. Centuries of oppression have caused communities of color to distrust data collection. History has shown them that time and time again, data has been used against them, not for them. That’s why it’s so important to build relationships and trust before going straight for the jugular and harvesting information from people you don’t even know.

It’s imperative to share first-hand knowledge and experiences of problems that people can relate to and want changed. By drawing an outline of the painting, and having a common understanding of what we are fighting for, only then can we begin to fill in the color with data and evidence that will convince policymakers to take action.

And to zoom out, it’s so important that we have shared principles and values around data. If we all act with the same respect for each other’s data, and understand that people are coming from a place of progress, it would make gaining people’s trust and improving others’ lives easier. No finger pointing, no accusations – just agreement.

In conclusion, data and relationship-building cannot exist in siloes. We need to bring together real stories with real passion for changemaking, and create visualizations of data which illustrate the problem clearly and call those who can make change to action.

Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Context or the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Tags

- Government aid

- Housing

- Social media

- Data rights

Go Deeper

Related

Latest on Context

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6