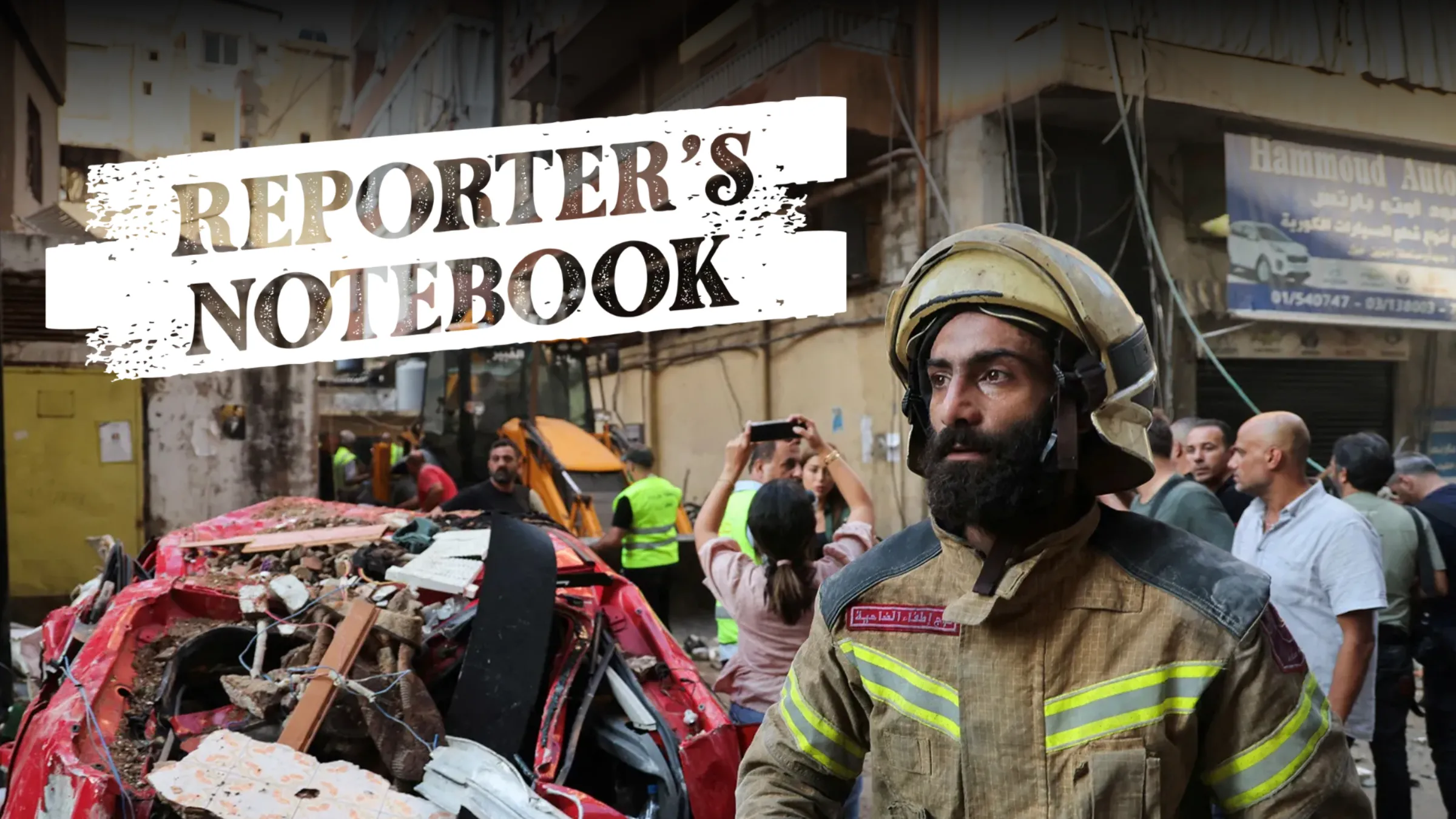

Reporter's notebook: War and want in broken Lebanon

A firefighter works at the site of an Israeli strike, in Beirut's southern suburbs, Lebanon September 24, 2024. REUTERS/Amr Abdallah Dalsh

What’s the context?

Our Middle East correspondent reports from Beirut, the traumatised capital of a country that can't afford all-out war with Israel

It was the deadliest day in Lebanon for decades but the young woman in Adloun, a coastal town near the southern border, said she wanted to go through with the online job interview, even as Israeli airstrikes hit buildings nearby and her children shrieked in terror.

My friend, who was carrying out the interview, told her she could reschedule.

But she insisted. What else could she do? She was terrified of missing a chance to work.

I understand her desperation. Lebanon cannot afford the conflict that is now unfolding across the country. Around 80% of the population has sunk below the poverty line since the economy imploded in 2019, the Lebanese pound has slumped and banks have locked most depositors out of their savings.

And now war has come and with it the threat of a wider collapse that could extend far beyond the country's borders and destabilise a whole region.

After almost a year of war in Gaza, Israel is shifting focus to its northern frontier with Lebanon, where Iran-backed Hezbollah has been firing rockets into Israel in support of the Hamas militants in Gaza, who are also backed by Iran.

On Monday alone, Israeli airstrikes killed around 500 people, including 35 children, and left nearly 2,000 people injured.

As the bombs fell across Lebanon this week, tens of thousands of people – whole families, women, children and the elderly – packed into their cars and crawled north on choked highways to the relative safety of my home town of Beirut, a once lively, cosmopolitan city.

But even here, safety is not assured.

On Monday evening, an apparent Israeli airstrike hit a building not far from my father's clothing shop in Beirut’s southern suburb of Dahiyeh. If it had happened any earlier, my father might have been one of the hundreds being ferried to the overcrowded, underequipped hospitals.

All day I could hear the piercing sirens of ambulances as they rushed down the highway near my home, ferrying the wounded.

It's a sound that had become all too familiar over the past days, a strident harbinger of what was to come.

Last week, pagers used by Hezbollah members - including fighters and medics - simultaneously detonated across Lebanon in what security sources told Reuters was an Israeli attack. At least 12 people were killed and nearly 3,000 wounded.

The bloodied survivors, some missing fingers, others with lacerated faces or missing eyes, and some with bodies flayed open by shrapnel, descended on the country's crisis-hit hospitals.

They were unable to cope then. They are unable to cope now.

"It's just like the port blast," I thought to myself after the news broke, remembering the 2020 explosion that destroyed much of the city and killed more than 200 people, while overwhelming doctors and hospitals.

Since that calamity - and because of it - the healthcare sector here has been on its knees. Hospitals were destroyed in the blast, funding dried up, and many doctors and nurses left the country for better prospects abroad.

I was in Beirut then too. My mind has largely shut out the trauma of that day but my body remembers whenever Israeli fighter jets buzz above the city, breaking the sound barrier over our heads as they stage mock raids, like they have been doing for the past month.

When this happens, I rush to the bathroom, the safest place in my apartment, feeling like prey stalked by an unseen predator. I know exactly how many steps I will need to make it there from my usual place on the couch – three, if you leap from your seat.

When I hear unexplained booms or bangs, I freeze and seek out the nearest human – my wife, or a friend. Our eyes meet in silent consternation before someone whispers 'car' or 'neighbour' – our code for, 'relax, it's not an explosion, it's not an airstrike'.

Sometimes, I laugh at myself, jumping at the slightest sound. And me with a concrete roof over my head.

I know others are far more exposed, those living in Gaza, those in south Lebanon, those already displaced from their homes with only a flimsy tent between themselves and the possible death from above that has defined almost a year of conflict.

(Reporting by Nazih Osseiran ; Editing by Clar Ni Chonghaile.)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Unemployment

- Wealth inequality

- War and conflict

- Poverty

- Cost of living